For patients and physicians, taking medications orally is often the most desirable way to administer drugs. Among other advantages, swallowing a pill is safer, more convenient and less invasive compared to injections or other ways to take a drug.

But one of the challenges oral pills face is getting digested by the stomach before they can deliver their payloads and carry out their intended effects. Because drugs that are degraded in the stomach are less effective, many treatments are currently unable to be taken by mouth.

As researchers in polymer science and bioengineering, we wanted to figure out a way to deliver drugs so that they could withstand stomach acid but still dissolve at the right place. In our recently published paper, we believe we have developed a new material that can help drugs do just that.

Oral drug challenges

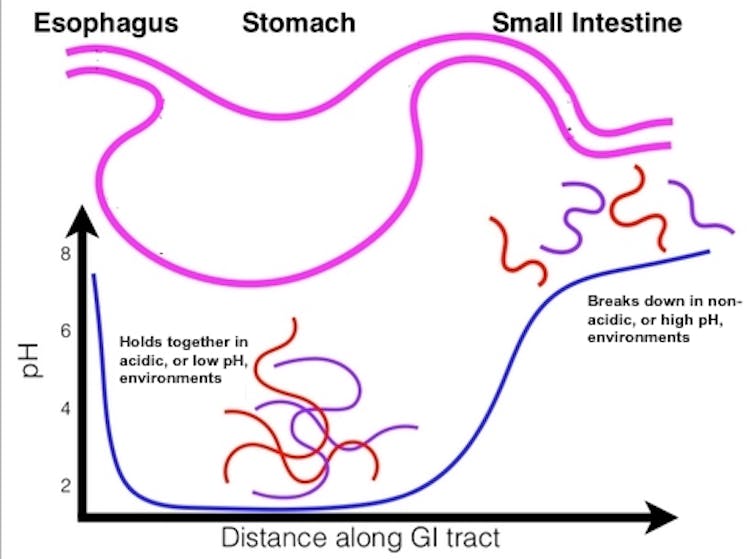

Oral drugs are primarily absorbed in the small intestine, where they subsequently enter the bloodstream and travel to the rest of the body. In order for a drug to get to the small intestine, however, it must first get past the highly acidic environment of the stomach, which can deteriorate medications before they can be absorbed.

To compensate for degradation in the stomach, oral medications typically come in doses that are higher than necessary. This strategy works for many common small-molecule drugs that have a low mass. They are often more stable and can more easily enter cells compared to other types of drugs. However, increasing dosage is not a viable approach for treatments that easily build up to toxic levels, are too sensitive to the acidity of the stomach or are very costly.

A stomach acid-resistant material

To help drugs withstand the harsh environment of the stomach, our research team developed a new type of material called polyzwitterionic complexes, or pZCs. pZCs are composed of two types of polymers, or large molecules made of a string of repeating smaller molecules. As the name suggests, pZCs are made of polyzwitterions, which are both positively and negatively charged, and polyelectrolytes, which are exclusively positive or negative.

Through a process called complex coavcervation that joins oppositely charged molecules, these two polymers self-assemble to form pZC droplets that are sensitive to acidity. In principle, these droplets could encapsulate and protect a therapeutic cargo as it travels through the highly acidic stomach, but disassemble and release the drug upon reaching the more neutral environment of the small intestine.

We first tested whether the pZC droplets were able to encapsulate a protein as a test cargo. Once we were successfully able to place the cargo in the droplet, we then measured how much protein cargo was released in varying levels of acidity through spectrophotometry, a method that uses light absorption to measure the amount of substance present in a sample. We found that the pZC droplets retained their protein cargo in acidic conditions and steadily released it as acidity decreased.

Making drugs more convenient

We believe that our pZC system can enable researchers to develop new and improved ways to deliver drugs through the gastrointestinal tract. Our future work will focus on better understanding how pZCs behave as their chemical properties change in different conditions. We are also experimenting with different types of polymers and drug cargoes.

Our hope is that our methods and conceptual framework will one day increase the number and variety of drugs that can be taken orally, making it more convenient to take your medicine and improving the lives of patients.

Khatcher O. Margossian has received funding from the National Science Foundation. No additional conflicts of interest are declared.

Murugappan Muthukumar receives funding from the National Science Foundation and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.