Books age at variable rates. Some, indexed to topicalities with mayfly longevities, are decrepit before they’re published. Others, lively and seductive on first appearance, are dry husks a decade later. More durable works may still feel noble a century hence, if suspended in aspic.

The rarest, bristling with baffling arcana and elaborate design, make brave bids for immortality. Their fate is the worst of all. It is the fate Benoit Blanc (Daniel Craig) and Marta Cabrera (Ana de Armas) discuss in Knives Out:

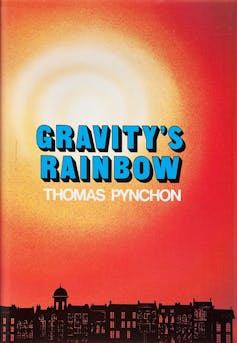

“Gravity’s Rainbow.”

“It’s a novel.”

“Yeah, I know. I haven’t read it, though.”

“Neither have I. Nobody has.”

On that august plane, Thomas Pynchon’s classic, 50 years old today, is a mere infant in the select company of Tolstoy, Milton, Cervantes, Rabelais, Dante, Ferdowsi and Homer – cradled by its siblings Ulysses (a puckish 101) and Moby-Dick (a swarthy adolescent of 172).

To many – including the Pulitzer Prize Board, who called the book “unreadable”, “turgid”, “overwritten” and “obscene” – such comparisons are a bad joke. To others – the faithful, the “Counterforce” the book convokes against the cult of death – Pynchon’s postmodern epic is our very own Iliad: the greatest hymn against war since Homer.

When she won the Nobel Prize for literature in 2004, Elfriede Jelinek, who had undertaken the mammoth task of translating Gravity’s Rainbow into German, responded:

It is a joke he hasn’t received the Nobel Prize and I have. […] I cannot receive the Nobel Prize as long as Pynchon hasn’t got it! That is against natural laws.

But when Pynchon won the National Book Award for Gravity’s Rainbow in 1974, he sent a comic, Professor Irwin Corey, to accept on his behalf with a speech of unbridled nonsense.

Doubts about its value are written into the text itself, which lurches wildly between the sublime and the ridiculous, monstrously scrambling its terms. Capable of the most elevated, soaring prose, of cadences that skate the angels’ wings and sound the utmost moral profundities, Pynchon is always ready to degenerate into schoolboy smut, atrocious puns, lewd humour and comic-book chases.

Short-circuiting the very language of literary value, permanently wrongfooting the custodians of taste, Gravity’s Rainbow proposes a new way of thinking about what we treasure most, what we fritter away, and what is taken from us.

Sloth or entropy?

Fifty years have seen the predominant theoretical paradigm for making sense of Pynchon’s vast novel – postmodernism – rise and fall like a V-2 rocket.

What survives of its collapse? Forget “magical realism”, forget “incredulity toward metanarratives”, forget the “death of the subject” – all those were merely code words for what Gravity’s Rainbow teaches its readers by default.

Since our whole “way of life” has been endlessly represented and sold to us as alluring images by the powers that profit from it, such prior representation must play a major part in the way artists access “reality” itself. Investing heavily in the wellsprings of human desire through advertising, entertainment, commercial literature, the movies, comics (etc.), capitalism has altered the historical ground on which we dwell. It has made it “hyperreal”. The human perceptual system can no longer directly access the social world around it. We can only do so via the enormous justifying edifice of commercialised fantasies.

So we enter the martial world of Gravity’s Rainbow, set over nine months in the European theatre in 1944-45, through the mediating scrims of Plastic Man comic books, 1940s pinup posters, Shirley Temple show tunes, radio serials, Laurel and Hardy routines, not to mention Fritz Lang melodramas, British spy thrillers, and endless musical interludes. The world of our pseudo-protagonist Tyrone Slothrop (“sloth or entropy” in anagram) is inseparable from this tissue of corporate fantasy projections, which he cannot distinguish from his own desires.

Pynchon’s prose refuses to tell apart what his characters cannot. As readers, we are treated to giant ambling adenoids, airborne pie-fights, séances with dead men, miles-high angelic apparitions, talking lightbulbs, a guest appearance by King Kong, and episodes of perverse sexual indulgence – all of which may or may not “really” have taken place.

Presented in a loping, circumvolving, maddening present tense, this siege on our sceptical faculty wears away all defences. Pynchon writes our collective psycho-sexual malaise into the framework of reality itself. We either confront it or throw the book down in disgust.

The minor characters are, consequently, mired in commercial cliché. Young women are constantly behaving like wannabe Betty Boops. (“Tits ’n’ ass,” mutter the girls, “tits ’n’ ass. That’s all we are around here.”) GIs lark like walk-on parts in Hogan’s Heroes. Black characters perform as “coons”. Gay characters are haunted by a veneer of “faggotry” that betrays their essence. Again and again, the “real thing” is suborned by its stereotype.

Against this destabilising ground, the enduring characters become more than the sum of their parts.

We encounter Oberst Enzian, the queer Herero questor with a name plucked from Rilke, and his Russian half-brother Tchitcherine, more steel than man, who is ruthlessly tracking down his Black sibling (their final non-encounter is one of the great turns in this book).

The spy Katje Borgesius appears as the beautiful reflex of all the depraved male appetites she must navigate.

Then there is Geli Tripping, the apprentice German witch with her owl familiar; the U-boat-hijacking Argentine anarchist Squalidozzi; Leni Pökler, the Jewish communist, who loses her daughter and ends up a sex worker on the Cuxhaven docks; Roger Mexico, the amorous statistician with a penchant for public urination; and “Pirate” Prentice of the famous banana breakfasts, with his talent for managing the fantasies of others.

Looming over it all is one of the great literary incarnations of evil: Lieutenant/Captain/Major “Blicero” Weissmann.

In an international cast of 400 named characters, any one of these creations would rank as a major achievement. To have all of them, weaving in and out of each other’s convoluted trajectories like tracer fire across a bombed-out city, is nothing short of a literary miracle.

Everything is connected

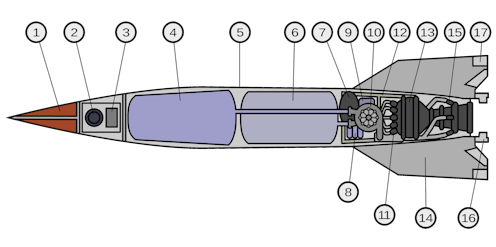

Such multiplying complications result in a fractal narrative technique. There is a grand story arc of sorts: a zig-zagging line concerning the V-2 rocket. But the novel is permanently susceptible to digressions, immersions, swerves, pro- and analepses. These have the uncanny trick of not diverting attention away from the main plot, but knotting into it.

Looked at properly, a plot is always total. The novel’s digressions are occult amplifications of a secret essence. Divagation becomes a knight’s leap into a hidden conspiracy that a safer connect-the-dots approach withholds. Pynchon – jazz-afficionado and arch-satirist – is a master of the riff, the routine, the set-piece. He has a comic’s improvisatory instinct to risk everything on a minor juvenile thought, escalate it into major-key hilarity. Yet everywhere the protocols of polite fiction are jettisoned for shits and giggles, a deeper truth emerges.

Gravity’s Rainbow is a book of markets – not the official market, but a far more radical “black” or ur-market where everything is directly exchangeable for everything else. Markets engender a specific way of seeing the world as parts of a single substance: value. Whatever exists can be broken down, and broken down further, into molecules of value. And value keeps the wheels turning – the wheels that stretch us on the rack.

Thus the great One of our world becomes an infinite multitude of alienable things. But that multitude masks a unity.

“Everything is connected, everything in the Creation”: this Whitmanian insight, shared with Melville and Joyce, is the ontological underpinning of Pynchon’s mindboggling formal audacity. The world is a unified field; it is power that insists on seeing it as discrete entities.

Take War. What if “World War II” were simply an entertainment for the masses, a violent participatory piece of performance art, a pretend “event”, behind which the secret history of the world was being written in blood and oil and deeds?

“They” may persuade us that wars end and peace prevails, but violent domination by a tiny elite is a constant. Industrial carnage, ecocide, the extinction of species, genocide: what McKenzie Wark calls the “Carbon Liberation Front” has engendered a total war without end – a dredging up of fossil fuels to perpetuate a turbo-fuelled death cult. Pynchon was the first great artist to apprehend it clearly:

We have to carry on under the possibility that we die only because They want us to: because They need our terror for Their survival. We are their harvests.

With war comes the state, a social form that thrives on dependency, control and inequality. It fatally inscribes itself into the living fabric of our collective being by way of markets, technologies, disciplines, and the routine sacrifices of millions upon millions of unwitting “sheep”. Pynchon’s novel identifies the War-State, the Cartel-State, the Rocket-State, as our collective destiny.

In Gravity’s Rainbow, the big nameable events with which we domesticate the war as history are mere whispers and distant rumours, never settling into definition. D-Day, the Surrender, the dropping of the Bomb – it is as if they never happened and have no value as narrative punctuation.

The present tense immerses us in a tempest of incident, implication and consequence. It imparts an awful lesson: the war never ended, just as it never began. War has always been, will always be, and we are its humble foot soldiers, meant only to die or, at best, submit to its absolute trauma.

Against this fatal transcendence the only plausible Counterforce is immanence, Eros, and laughter.

Pynchon has his own metaphysic, a binary structure that simplifies human history into two fundamental camps: the Elect – those chosen to rule, benefit and endure – and the Preterite, the “great Humility” of the masses, with no specified role in the pattern beyond cannon fodder, cheap labour and consumption.

The Preterite are bound to lose. Yet on our side are all the nameless, incandescent forces weaving the cosmos together in its great dancing affirmation of life and creation and love. For no good reason, we fall into one another’s arms and beds and have our designated identities undone.

Pynchon is, with Blake, Shelley and Emma Goldman, one of the frontline militants of sexual love as an antidote to authority and control. In one the book’s great set-pieces – “a brief segment of a much longer chronicle, the anonymous How I Came to Love the People” – we are given to understand that against “Their” sinister plot of death and nihilism, we can always rely on “horny Anonymous’s intentions”:

nothing less than a megalomaniac master plan of sexual love with every individual one of the People in the World –.

Escaped chimps, congregating pigs

Animals attain rare agency and character on the pages of Gravity’s Rainbow. An escaped band of chimpanzees wreaks havoc in the Russian sector. Pigs congregate and exert increasing symbolic potency. Ownerless trained dogs establish a “Hund-Stadt” in Mecklenburg. A lemming draws frantic lines of passage outside Wismar. Grigori the trained octopus stages a monstrous assault on a “damsel in distress” to draw Slothrop deeper into his fatal intrigue.

Beyond that, the inanimate world is made dynamically animate. A light bulb is given a lengthy biography. Pinball machines rewire themselves. A new polymer is sexualised. Fungus Pygmies sing acapella “on the other side of […] the whole bacteria-hydrocarbon-waste cycle”.

At the deepest level, molecules do not seek independence, but ever more complicated bonds and ties. Fusion, not the fission that detonates over Hiroshima, will out. Life insists on its becoming, even under the mushroom clouds.

Attuned to such frequencies, we might yet hear the Titans’ roar, be brushed by their astonishing beauty and immensity, as they gaze on in melancholy resignation at our undoing. Rilke’s Angels are conflated with these guardians of the World:

In harsh-edged echo, Titans stir far below. They are all the presences we are not supposed to be seeing – wind gods, hilltop gods, sunset gods – that we train ourselves away from to keep from looking further even though enough of us do, leave Their electric voices behind in the twilight at the edge of the town and move into the constantly parted cloak of our nightwalk till

Suddenly, Pan – leaping – its face too beautiful to bear, beautiful Serpent, its coils in rainbow lashings in the sky – into the sure bones of fright –

Here is all the myth we need. Pynchon ultimately leads us on a dance with the vital, pulsing demiurge of things, back to the rhythms of creation and chaos from which we once emerged. But to get us there, he must first paint a Boschian hellscape. He leads us through a valley of depravity, treachery, horror and slaughter.

Comparisons with Dante, Milton and Homer are finally earned, not by the superficial features of the book, but its deepest project: to sing the “vast Humility”. Gravity’s Rainbow treats the “multitudes who are passed over by God and History” as an epic subject in its own right.

The novel also marks a major moment of transition: from an aesthetic theory based on resemblance (analogy, metaphor, symbolism, etc.) to one predicated on the infinite fungibility of molecular matter and the omnipresence of electronic signals.

Like older modernist tomes, Gravity’s Rainbow is structured around mythic templates: the Christian liturgical calendar, the Tarot pack, the Kabbalah, Teutonic legend, mandala structures. All supply handsome struts and arches on which the text assembles its diffuse materials.

Resemblance is the key: a rocket seen from above looks like a mandala, which resembles a Herero village; images plucked from the Tarot are layered onto mythic and religious icons because they share the same functions, the same occult regalia. But somewhere along the arc of the 20th century (at Brennschluss perhaps), this analogue regime of signs and portents gave way to a new order of the Real: codes, chemical bonds, signals processing, mathematical formulae and commands.

Our dominant ways of thinking about the arts have yet fully to catch up with this momentous change, but Pynchon’s great book was always already thinking about it. Gravity’s Rainbow adapts its narrative language, finds rare moments of transference and overlap. It trains its readers how to read engineering reports and chemical analyses as ways of thinking about the nature of art.

There is nothing in contemporary literature to compare with it, certainly not in English. All the lesser pretenders – John Barth, Richard Powers, David Foster Wallace, Jonathan Franzen, even Don DeLillo – seem small and trivial in the glow of its mad quasar-pulses of brilliance. The risks taken here, in 1973, are so astonishing in retrospect largely because of everybody else’s incapacity to match them.

The burning question will always be: for whom was Pynchon writing? There was no ready readership for a book composed of such disparate, off-putting materials and crazy shifts of tone.

Yet Gravity’s Rainbow created one from scratch, the way Einstein created a new image of the universe and the universe rearranged itself accordingly. If the novel finds you, it conscripts you. You are absorbed into its army of believers. Like Serena Williams in the sequel to Knives Out, who is caught with the book in her hands, you are on the brink of a new career in “the race and swarm of this dancing Preterition”.

Do yourself a favour. The world is dying. Join the Counterforce.

Julian Murphet does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.