Steve Braunias on the appearance of a new book of James K Baxter's poetry

Four years after a book of James K Baxter's letters was greeted with widespread disgust at his admission to raping his wife, and it seemed he was likely cancelled for all times, a new collection of poems has been published – a best-of, 300 poems chosen from the 3000 he wrote up until his death in 1972 at the age of 46. Baxter, again; Baxter, seemingly, always.

James K Baxter: The Selected Poems is the latest book in "the Baxter project" initiated and edited by his close and loyal friend, John Weir, a scholar and Marist priest. It's also his last book: Weir is 88, and Selected brings to a close his epic mission to collect and curate everything Baxter ever wrote. I phoned Weir at his rest home in Christchurch. He said, "I first began the Baxter project on the day that I travelled to his funeral in 1972."

Fifty years! It's an amazing service, an incredible act of dedication that resembles devotion. Weir edited James K Baxter: Complete Poems, which ran to four volumes. He edited James K Baxter: Complete Prose, another four volumes. He edited James K Baxter: Letters of a Poet, two volumes. The new edition of the selected poems (a mere 332 pages) is the most personal of Weir's books: it's his farewell note, his own say on the best of Baxter.

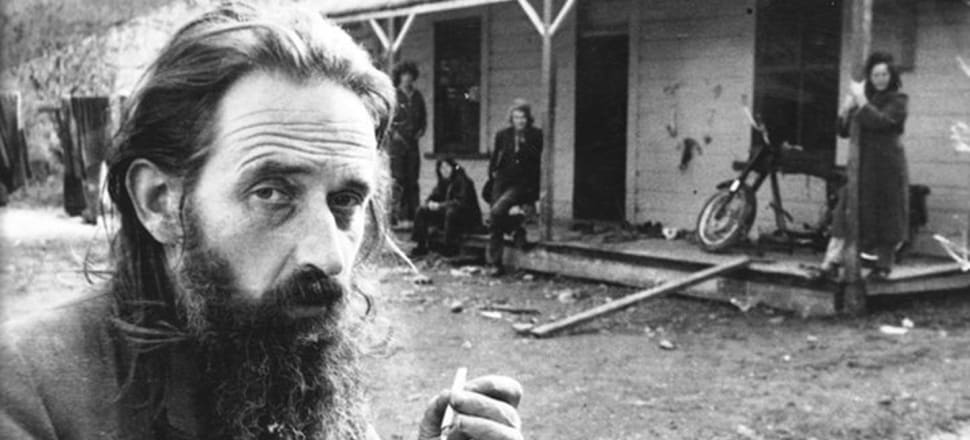

For so long Baxter was fixed in the public mind as a genial hirsute bum with a heart of gold. Good old Hemi, who followed the instructions given to him by God to go to Jerusalem, on the Whanganui River, where he founded a kind of shelter for the lost, the criminal, the insane, the merely curious. He was bicultural, he appeared to possess a kind of holiness. But the letters about his wife, writer Jacquie Sturm, give him a new, darker fix. "Sex relations with wife resumed," he wrote to a friend in 1960. "Achieved by rape."

Never slow to speed into brute tabloidese, I was the first to break the revelation by publishing a long and thoughtful review by John Newton, with the short and horrifying headline, 'James K Baxter, rapist'. Newton wrote, "It won’t be a surprise if, for many potential readers, this statement ['Achieved by rape'] comes to drown out everything else that Baxter wrote. …Has Baxter, then, arrived at his #metoo moment? Something of the kind seems inevitable."

But to be #metoo'd is to be banished. The appearance of the new Selected brings forth once more the Baxter voice, his nature poems, his satires, his sonnets, his stupid asides ("The housewife with her oyster c**t", etc). Curiously, the book is co-published, by Cold Hub Press in Lyttelton, and Te Herenga Waka University Press. I asked Roger Hickin at Cold Hub how it came about. His answer was quite taciturn, but with a possible sting: "A matter between Fergus Barrowman, John Weir, and me. All I can say is that John wanted me involved." I put the same question to Fergus Barrowman at Victoria University. He replied, "Initially he [Weir] thought Cold Hub – who published his poems a year or two ago – would do it, but we wanted in on the act." Barrowman had published the 10 volumes of the various Collecteds, as well as numerous works about Baxter; he didn't want to pass up this opportunity to associate the University Press with Baxter. "Baxter was a really good writer and astonishingly productive but also a really interesting figure in cultural history who has mattered to a lot of people, so there is a lot to talk about."

Both co-publishers acknowledged the vileness of the rape letter. Both seemed to regard it as something that Baxter's reputation could accommodate.

Hickin: "Baxter was as deeply flawed as he was deeply humane. In terms of his misogyny, a man of his times. I think even many of his surviving friends have realised only recently just how flawed he was. Perhaps it was his own recognition of his failings that made him so open to others. As long as humanity isn't totally corrected by the paragons of cancel culture I reckon the best of Baxter has a chance of surviving."

Barrowman: "The way Baxter outing himself as a rapist played out was unfortunate. I thought we’d done the right thing by neither suppressing it nor advertising it, but once it was out it stopped all other conversation, which is a real shame because the Letters is a treasure trove."

Weir, too, thought that the rape controversy drowned out serious critical consideration. "The reviews of the letters as collections of writing was entirely lost sight of," he said. This is not entirely accurate. John Newton's 3400-word review discussed Baxter's letters to his mother, and to writers such as Fleur Adcock, Charles Brasch, and Hone Tuwhare.

Newton also wrote, "Spare a thought for John Weir. Not simply Baxter’s tireless editor, but equally his loyal friend, assembling this book he can’t but be fearful of the damage it threatens to the poet’s reputation." This is entirely accurate. I asked Weir about the moment he found the offending letter.

He said, "I discovered the letters to Phyl Ferrabee in a library collection. I was about two-thirds of the way through some years of research. I thought, 'Well, where we are. I've found them, and I now don’t want to be the one who publishes them to the world', and I had to make a choice. I thought, 'One thing I can't do is publish the letters but not include this particular letter referring to the rape of his wife. I can't do that.'

"Therefore I had to either continue to publish the letters and include it and face up to it, or I have to resign from everything. I consulted with some people about it, and was convinced to continue with the project. Over time it would have become public knowledge anyhow, somehow, sometime."

I asked, "But you actually did think of stepping away from the whole thing?"

"Yes," he said. "That became one of my serious considerations. At the same time I was also working on the Complete Poems as well as the letters. So I would have been stepping away from the complete project as well as the particular volume of letters."

I asked, "Was it a matter of conscience?"

"Everything was a matter of conscience," he said. "But it was very clear to me what my choices were. It was difficult. Whatever happened was difficult."

He went with it. The letter came out. The condemnation followed. Weir writes in the Introduction to Selected Poems, "While the revelation quite properly caused severe damage to his reputation as a man, it should also be said that, despite the preoccupation with sex and despite the serious offence he committed, he also gave direction and compassionate assistance to hundreds of people, young and old."

But rape is rape. What will the future make of James K Baxter, rapist? I asked Weir, and he said, "I can't predict that. I'm happy not to be able to predict that. None of us can predict how the future will pan out. Things will fall the way they are going to fall. What will happen, will happen."

Weir was heading towards a "but" in that answer and finally came to it: "But it seems to me – well, Baxter had an ambiguous personality. He recognised that. He referred to himself in one poem as, 'Baxter, Baxter, my enemy/ With ropes of need you fasten me/ With many words you gag my mouth/ With deeds you murder me.' He's talking to his other self. Several times in his poems he refers to this kind of split in his personality between the one who wants to be compassionate and helpful to all, and live lightly in the world, and the one that takes advantage of others. That's the struggle he faced until his death."

Baxter died of a coronary thrombosis on the sofa of a house in Grafton. Weir provided the following background. Hone Tuwhare's wife Jean had driven Baxter to see their family doctor. He was in poor health. Midway through the consultation, the doctor was called away. He told Baxter that he looked alright and to come back later if he was still feeling unwell. Baxter dressed, walked outside, and had a heart attack. He had a vague idea he knew people across the road, and knocked on their door. They didn't know him at all. But they let him in, and gave him a glass of water. It was a saint's death – the kindness of strangers, giving him shelter – and there was a sense of consecration at his tangi. Hundreds of mourners; a requiem mass; Ans Westra's famous photograph of Hone Tuwhare staring into the open grave.

And now? John Newton wrote in his review of the Letters, "Whatever kind of hit his reputation may sustain from this, I don’t doubt that his work is resilient enough to survive it." Newton is one of the great chroniclers of Eng Lit in NZ. His 2007 survey Hard Frost: Structures of Feeling in New Zealand Literature 1908-1945 is a modern classic. (I rejected his own suggested headline for the Letters review, "Mythopoetics and Bush Psychology", as far too brainy). Jane Stafford, professor of English at Victoria University, is another great chronicler; with Mark Williams, she was co-editor of The Auckland University Press Anthology of New Zealand Literature, still the biggest book ever published in any language, possibly. Her revised thoughts on Baxter's poetry, which she had previously enjoyed: "Laboured ... self-regarding ... bombastic."

She very recently taught his work as part of a historical survey of New Zealand writing. The students were bored; she was, too.

"I think the social critique part of Baxter has dated really badly. And it sort of shouldn't have. The poem 'The Maori Jesus' writes about the poor and dispossessed, which should chime in with things we're worrying about now. But halfway through the people he's listing is the housewife on the contraceptive pill and how she's going to throw away the pill and free herself and you just think, 'What?'

"And the satires, like 'Letter to Sam Hunt', are very misogynistic, in a revolting way now. I mean I think they always were really but I think that’s more noticeable now."

I asked, "Are you criticising the poetry, at the level of language, or the social critique, because it's dated?"

"It's not just dated," she said. "It's sort of highly unpleasant. And one of the things about Baxter is that he was the great prophet of biculturalism and I don’t know where he would fit now in the way we view that sort of thing. I think that maybe his use of Māori material would not be viewed as appropriate."

I asked, "But that’s a false economy, isn't it? He wouldn't be saying those things now."

"Hm. No. No," she said, meaning she agreed that was so. "I think perhaps he wouldn't be saying those horrible misogynistic things but he's not here now. We're just reading him now, aren't we. But it's not just his opinions. For me, reading him again now, the poems just seem a bit flabby. The poetry doesn't really have a crispness to it somehow."

I asked, "How much of this revision of his work is due to the shocking letters?"

"I haven't read the letters," she said. "One of my students asked me about it. But she didn't like the poetry. It wasn't the person, it was just the poetry that the students felt alien to."

And yet the work survives, and deepens. Catherine Chidgey won the Jann Medlicott Acorn Prize for Fiction at the Ockham book awards in May for her novel The Axeman's Carnival; it opens with lines from the poem "High Country Weather":

Upon the upland road

Ride easy, stranger.

Surrender to the sky

Your heart of anger.

The lines are by Baxter, from the very first poem in the new Selected. Another, later poem, 'The Cold Hub', caught my eye. I asked Roger Hickin at Cold Hub Press whether it had inspired the name of his publishing imprint.

He said, "You're right. When I began publishing poetry in 2009, I was looking for a name. Thought I'd flip the Baxter: Collected Poems open and see if anything leapt out. It opened at 'The Cold Hub'. Not surprising really. One of my favourite Baxter poems. As I was a youthful alcoholic myself it was one that had always resonated for me."

The stone of Baxter's poetry, still rippling over the waters of New Zealand letters ... Much of the credit is due to John Weir, and his indefatigable enterprise, for keeping Baxter's work alive and in the present. John Newton, on John Weir: "No one has laboured harder in the Baxter archive, and the poet and his readers alike owe him a huge debt of gratitude." Roger Hickin on John Weir: "Despite Charles Brasch's snooty remark in his diary ('I can't see myself allowing any R.C. priest to make free with my papers') it was a lucky day for Baxter when he struck up a friendship with Father John Weir."

Friend, disciple – Weir prefers the term amanuensis, to describe his life's work in service of the writer who so dominated the narratives of 20th Century poetry in New Zealand. Baxter's writing shows you inside his heart and mind, reveals his failings and his unpleasantnesses. But I was interested in what he actually looked like, in person, on the surface. Short, said Weir, with blue eyes. "A very pleasant face that lit up when he met you." Polite, courteous. "He had the ability to transform a room of people when he came into it. The conversation subsided and attention turned to him. He was not only an elegant speaker but he had fascinating things to say."

I asked, "Was he a monologist?"

"He was very much a monologist," he said. "That is so. And to that extent it coincided with his poetry in a way. He conducted a nonstop dialogue or monologue in his head; he was always thinking about all kinds of things, and then when he met someone, he was very likely to simply say to them the next sentence that was occurring in his mind. He met a friend of mine once who didn’t understand him at all, and said how puzzling he was. My friend put out his hand to shake Baxter's hand and Baxter put out his hand, and said, 'Did you know that whatever you give to a poor man, according to St Francis de Sales, goes through his hand into the wounded hand of Christ?'

"Someone meeting Baxter for the first time would be totally thrown by that. They have no context against which they could reply, but it was just what he was thinking at the time and so he said it. He had a nonstop monologue going in his brain and the poems are very often chopped-up versions of the monologues going on in his head."

Baxter, writing out loud; Baxter, seemingly always writing out loud, then putting it to paper, sometimes grossly, more often brilliantly (see below: "Stiff as a giraffe"!), all of it preserved in 11 volumes by a friend who loved him.

The Cold Hub

Lying awake on a bench in the town belt,

Alone, eighteen, more or less alive,

Lying awake to the sound of clocks,

The railway clock, the Town Hall clock,

And the Varsity clock, gentle, exact

As a Presbyterian conscience.

I heard the hedgehogs chugging round my bench,

Colder than an ice-axe, colder than bone,

Sweating the booze out, a spiritual Houdini

Inside the padlocked box of winter, time and craving.

Sometimes I rolled my coat and put it under my head.

And when my neck got frozen, I put it on again.

I thought of my father and mother snoring at home

While the fire burnt out in feathery embers.

I thought of my friends each in their own house

Lying under blankets, tidy as dogs or mice.

I thought of my med student girlfriend

Dreaming of horses, cantering brown-eyed horses,

In her unreachable bed, wrapped in a yellow quilt,

And something bust inside me, like a winter clod

Cracked open by the frost. A sense of being at

The absolute unmoving hub

From which, to which, the intricate roads went.

Like Hemingway, I call it nada:

Nada, the Spanish word for nothing.

Nada; the belly of the whale; nada;

Nada; the little hub of the great wheel;

Nada; the house on Cold Mountain

Where the east and the west wall bang together;

Nada; the drink inside the empty bottle.

You can't get there unless you are there.

The hole in my pants where the money falls out,

That's the beginning of knowledge; nada.

It didn't last for long; it never left me.

I knew that I was nada. Almost happy,

Stiff as a giraffe, I called in later

At an early grill, had coffee, chatted with the boss.

That night, drunk again, I slept much better

At the bus station, in a broom cupboard.

James K Baxter: The Selected Poems edited by John Weir (Cold Hub Press and Te Herenga Waka University Press, $40) is available in bookstores nationwide.