Close contacts of people with COVID in New South Wales and Victoria will soon no longer need to isolate for seven days. Other states and territories, including Queensland and the Australian Capital Territory, are considering or will likely announce similar moves.

In NSW from 6pm tomorrow and in Victoria from just before midnight tomorrow, close contacts of COVID cases no longer need to isolate at home, so long as they test negative for COVID, and follow other rules designed to limit the spread of the virus.

The move frees up close contacts to return to work outside the home, but carries a slightly increased risk of the virus spreading to the wider community. However, not everyone agrees whether even this small risk is worth taking.

So what is the risk of a household contact catching COVID? And what else could we be doing to minimise the risk to the wider community after isolation rules are relaxed?

What’s changing?

The upcoming changes in NSW and Victoria relate to the isolation requirements of close contacts only. People with COVID still need to isolate for seven days.

Details of what this means for close contacts in NSW or Victoria differ slightly. However, governments are sensibly asking close contacts to take a number of measures to reduce the risk of them infecting other people. These include:

working from home where possible

telling their employer they’re a close contact

wearing a mask indoors when they are outside the home

taking multiple rapid antigen tests over seven days

avoiding contact with immunocompromised and elderly people

avoiding vulnerable settings such as residential aged care services or hospitals

These will reduce the already low risk of passing on the virus even further.

Read more: Time to remove vaccine mandates? Not so fast – it could have unintended consequences

Why now?

These changes come after much lobbying from business groups and some unions who say their members are struggling with so many workers off with COVID, or from being a close contact of someone infected.

We’ve also seen schools, airports and other sectors struggling to find workers.

The changes also follow the loosening of isolation requirements for close contacts made in January for several categories of essential workers, such as emergency and childcare staff.

So many of us are immune

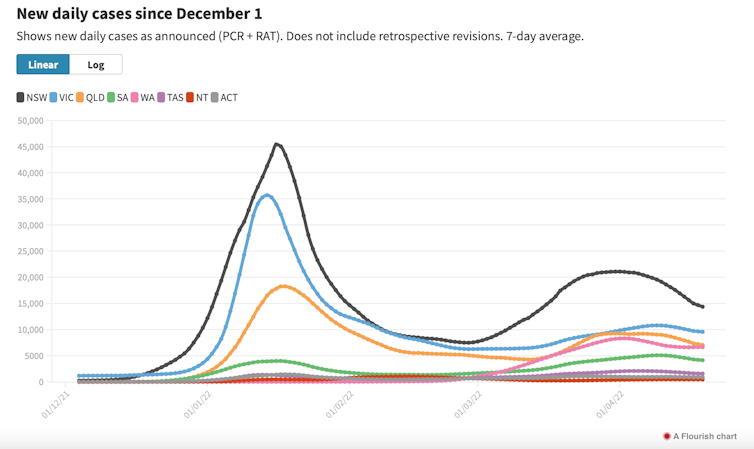

All states and territories have now gone past the second Omicron peak, caused by the BA.2 subvariant. Western Australia never had the BA.1 wave because of its closed borders, and is now also coming off the peak of its BA.2 wave.

With about 50,000 diagnosed cases a day, Australia is still in the grip of a massive outbreak, and the true number of daily cases is likely several times this.

This is because the percentage of asymptomatic infections is estimated at 25-54%, so many individuals wouldn’t think to get tested. Not everyone who feels unwell will get tested. And even if people test positive with a rapid antigen test, not everyone will report it to the authorities.

So, the majority of people in the community either have natural immunity from infection, vaccine-induced immunity, or both (hybrid immunity). It is timely, therefore, to ask whether isolation is still essential for close contacts.

What is the actual risk at home?

If you live in a household with someone infected, what is your risk of catching the BA.2 subvariant of Omicron, which is dominant in Australia?

Despite being highly contagious, there appears to be only a 13% chance you will get infected. So the risk is actually quite small.

Read more: BA.2 is like Omicron's sister. Here's what we know about it so far

How about the risk to the wider community?

At the moment, about 20% of PCR tests in Australia are positive on any single day, reflecting a massive amount of infection in the community, much of it undiagnosed.

However, because of the high degree of immunity in the population, and the relatively low contribution of the close contact rule changes to transmission risk, I don’t believe the changes will have a major impact on case numbers. The changes will also bring a big relief to business.

What needs to happen next?

For these changes to avoid driving up case numbers, we need to assume close contacts do the right thing – mask up, avoid contact with vulnerable people outside the home and regularly test themselves. Let’s hope this happens.

Finally, daily rapid antigen tests (under some circumstances) for close contacts will be expensive. Imagine a family of five where one person is infected. That is up to 28 rapid antigen tests for the four close contacts, at about A$10 per test.

At the moment, only concession card holders get a free limited supply of rapid antigen tests. So governments will seriously have to consider some sort of subsidy for close contacts, or better still, supply them for free.

Adrian Esterman receives funding from the NHMRC, the MRFF and the ARC.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.