Catalytic converter thieves have struck more than 17,000 times in Chicago since 2019. And they almost never get caught.

Only 34 of those reported thefts — 0.2% — ended with an arrest, a Chicago Sun-Times analysis has found.

“They just zip, zip, and Sawzall it out and leave,” says Shannon Cason of Edgewater, who had a catalytic converter stolen in December. “Nobody knew.”

The thieves — often the bottom level in organized crime rings — have hit every part of the city.

Replacements and repairs typically cost between $1,000 and $2,500. That comes to more than $17 million lost to catalytic converter thefts in Chicago since 2019.

Police are trying to go after the criminal cutter crews and the illicit metal buyers, with little success.

An Illinois law enacted last year targeting scrap metal sales has barely put a dent in the illegal trade. In the months after it took effect, the number of thefts rose even higher.

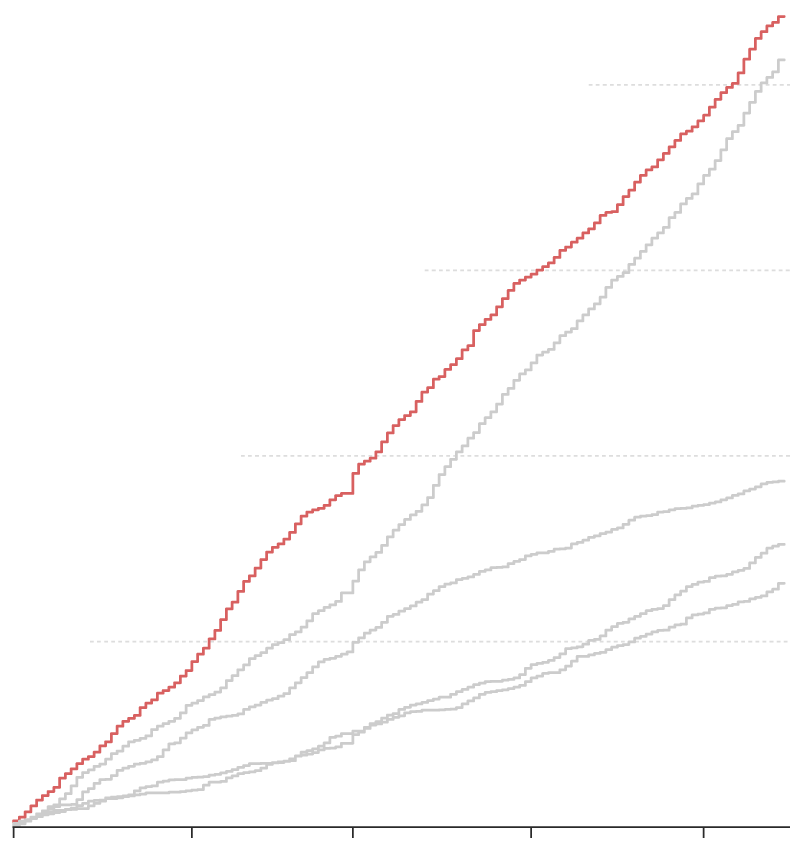

The Sun-Times analysis, based on Chicago Police Department reports covering January 2019 through the middle of last month, shows the number of thefts shot up in the fall of 2021 and exploded last summer.

And those 17,806 reports certainly understate the problem because many victims never file a police report, and reports of some thefts that escalated into violence were recorded differently.

Cumulative catalytic converter thefts from January 1 to May 15

Cason didn’t file a police report when his ex-wife’s Toyota Prius, which he’d offered to watch while she was out of town, was targeted by thieves on his quiet block in Edgewater.

“I go to start her car, and it just sounds terrible,” he says. “It’s just like a diesel engine or something.”

The thieves carved up the underside of the car, causing $1,500 in damage.

Cason, a professional storyteller and podcaster, turned his frustration into a performance for “The Paper Machete” show earlier this spring at the Green Mill in Uptown. When he asked who’d experienced a catalytic converter theft, half of the audience raised a hand.

And, he says, “Some people said, once they got it fixed, they stole it again.”

Top target areas, how thefts work

Some of the worst neighborhoods in Chicago for catalytic converter thefts, adjusted for population, were: West Town, Avalon Park, Irving Park, Logan Square, North Center, the Lower West Side, Lincoln Square, the Near West Side, Jefferson Park and Avondale.

Catalytic converter thefts expand into south and west sides alongside number of thefts

2019

2,367 thefts

2020

2,159 thefts

2021

3,478 thefts

2022

7,618 thefts

2019

2,367 thefts

2020

2,159 thefts

2021

3,478 thefts

2022

7,618 thefts

Once operating mostly at night, catalytic converter thieves in Chicago have grown brazen, hitting cars in broad daylight in busy areas.

It happened to Tony Rivera, a retired police officer. One Friday morning in late April, he ducked into his neighborhood Jewel near Ashland and Wellington avenues in Lake View. Ten minutes later, when he got back to his 2000 Acura TL with his groceries and started it up, he heard the roar of a missing catalytic converter.

Rivera was lucky. He has a friend who works in a muffler shop who fixed it for $525, $25 more than his insurance deductible would have been. He didn’t bother to file a police report.

“It’s aggravating,” he says. “You feel betrayed. But that’s life.”

Law enforcement and industry experts say the thieves know which models they’re looking for and sometimes will scout cars that are regularly parked in the same spot.

The data service CARFAX estimates that about 153,000 catalytic converters were swiped nationwide in 2022.

The thieves are after three precious metals the devices contain — platinum, palladium and rhodium. Those act as catalysts inside the honeycomb-like core, turning harmful exhaust emissions like nitrogen oxide and carbon monoxide into less harmful gases.

Since the 1970s, catalytic converters have been mandatory for all internal combustion engines under the federal Clean Air Act. Electric cars don’t have them because they produce no emissions.

The thefts start with “cutters,” usually groups of three or four young men, often in stolen vehicles, often armed.

Videos capturing the crimes typically show someone standing guard while another crawls under the car with an electric saw to cut off the “cat” or the “vert,” slang for converter.

They’re gone in as little as a minute.

Cutters can make anywhere from a couple hundred dollars to $1,500 for each stolen converter from an “intermediate buyer” or middleman, depending on the vehicle, experts say. Some take drugs in payment.

The middlemen create fake documents to make it seem like the converters are from legitimate sources, like a wrecked car.

From there, according to court documents in a recent federal case targeting what authorities say was a nationwide catalytic converter theft ring, stolen converters are sold to “core buyers,” businesses that extract the powdered metals.

The core buyers in that federal case were shockingly well-organized, offering dynamic pricing based on how the metals were trading globally and giving cutter crews real-time info on vehicle models to target, authorities say. Toyota Priuses from 2004 to 2009 were especially desirable.

The stolen converters go through “decanning,” where the core buyers use special machinery to crush the structure inside converters to extract the powder containing the precious metals.

The powder is sold to metal refineries that pay based on the amount of precious metals.

The metals ultimately end up being used in the production of chemicals and plastics as well as in medical and dental devices, cancer treatments and electronics.

Platinum recently has sold for about $1,037 an ounce, palladium $1,429 an ounce and rhodium $6,300 an ounce.

In recent years, platinum hit a peak of $1,289 an ounce in February 2021. Palladium — much of it mined in Russia — hit $3,307 in February 2022. Rhodium reached a whopping $29,800 an ounce in March 2021 — 17 times the price of gold.

Consumers pay the price for this. Car repairs can reach $5,000 for high-end vehicles or in cases where the entire exhaust system needs to be replaced and damaged electronics repaired, says Robert Passmore, vice president of the American Property Casualty Insurance Association.

From thefts to violence

On social media sites, catalytic converter thefts are a commonly reported nuisance. But sometimes the thefts escalate into violence.

Last August, a Rogers Park man was shot twice after confronting catalytic converter thieves he noticed under his vehicle in the 7200 block of North Oakley Avenue.

In November in West Lawn, a cutter crew sprayed a house near 69th Place and South Lawndale Avenue with 17 gunshots after a witness opened a window and yelled at them. No one was hit, but the family described feeling terrorized.

A 58-year-old man who lives near Roscoe Village on the North Side and was shot twice last July when he interrupted a theft crew describes the lasting trauma he’s experienced.

The man was in his back yard with his dogs on a sunny Thursday when he heard an electric saw grinding metal near where his 2015 Toyota Prius was parked. He ran over and yelled at the group of thieves, who appeared to be teenagers.

“I knew exactly what they were doing, right away, and I went out on the porch and I said specifically, ‘Hey, get away from my car,’” said the man, who agreed to speak on the condition he not be identified out of fear of retaliation. “As soon as I said that, they drew a weapon on me and started firing.”

Shot in his abdomen and one foot, he took cover behind a big tree and later found another bullet hole, a shot he says could have killed him.

“I felt the one in my foot first, but it was like such a minor sensation with the adrenaline, and then I felt one in my abdomen, and I knew I had to get out of there.”

The thieves sped off. Neighbors came running with towels for the bleeding until an ambulance arrived.

His hospitalization cost about $40,000, of which he says he had to pay about $800 after insurance.

The man considers himself lucky to be alive but says he has experienced post-traumatic stress. He sought counseling through a state-funded program for victims and says it has helped.

He remains frustrated, though, that no one has been arrested.

“The parents of juveniles that commit crimes are failing their children, and I feel like it’s just the first step in a long line of failures for that child,” he says.

Few thieves get caught

In Chicago, only about 0.2% of the catalytic converter-related theft reports to police resulted in an arrest, the Sun-Times found — in line with arrests elsewhere.

That’s frustrating to Laura Poskus, who paid a $500 insurance deductible plus $80 for a rental car after a crew did $3,700 in damage to her Honda CR-V last winter.

Poskus was at work in Avondale on the North Side around 4:50 p.m. on Feb. 15 when she heard a noise from the parking lot where her sport-utility vehicle was parked. She looked out and saw a black Audi sedan next to her vehicle and someone fiddling around underneath.

“I saw the jack, and I just screamed,” Poskus says. “I literally screamed out of anger.”

In a video captured by cameras in the parking lot, the crew of four attacks her SUV in under three minutes. They throw her converter and their tools into their trunk, where another sawed-off converter is already stowed.

Poskus says she called 911 and was transferred to a person whose “first response was, ‘Well, you should just get it fixed,’ ” she says, that their “system was down,” and they could not take a report.

So Poskus went to a police station, where she says, despite having an identifying number that had been stenciled on the stolen converter, she was told, “I can put it in the report if you want me to.”

Poskus wonders about people who can’t afford a big repair.

“If something like this happens that you didn’t plan, you gotta put it on a credit card, and you’re making payments on it,” she says. “That’s how people get in these horrible financial holes.”

Chicago police say they’re aware of “several organized crews” but that it’s hard to catch the cutter crews or tie converters to individual victims.

“Probably our biggest obstacle is catching them in the act. It’s so quick,” says Andrew Costello, commander of central investigations for the Chicago Police Department.

Costello and Glen Brooks, the department’s director of community policing, point to the violence that’s often involved with the thefts and say they are working with the Illinois secretary of state police, Cook County sheriff’s department, federal law enforcement and others to go after thieves and investigate the middlemen and metal businesses.

“We certainly don’t discount this as just a property crime,” Costello says.

Brooks encourages people who witness a catalytic converter theft to gather as much detail as possible to give police — but not to confront the armed crews.

“I understand the anger, I really do,” Brooks says. “But that anger is not worth your life.”

Undercover efforts

Police have made arrests in cases where they’ve noticed a theft pattern and caught people with jacks, electric saws and cut-off converters. The Cook County state’s attorney has prosecuted some cases as aggravated possession of a stolen vehicle, a felony, because stealing an essential part of a car is akin to taking the whole vehicle.

As rare as arrests are, consequential punishments have been rarer. In one case last year, a thief who was accused of swinging his saw and injuring a witness who tried to stop him from stealing a converter on the Southeast Side pleaded guilty to battery and got 60 days in jail. In a 2020 case, police stopped three men who had 10 cut-off converters and an electric saw. All were charged with misdemeanors and got sentences ranging from four days in jail to probation.

Lt. Adam Broshous of the Illinois secretary of state police, who heads the Illinois Statewide Auto Theft Taskforce, says the middlemen the cutters use have relationships with corrupt scrap metal businesses.

Undercover officers have tried to sell catalytic converters to suspicious scrap metal dealers, only to be turned away, Broshous says, because “they don’t know us.”

Attempts to use bait cars or watch parking areas to catch cutters have similarly failed, Broshous says: “The problem for law enforcement is you have to be in the right place at the right time to catch it. It’s very, very difficult.”

In its multistate case announced last November, the FBI and authorities in nine states stretching from California to New Jersey charged 21 people with operating a network of thieves, dealers and processors that pocketed $545 million from stolen converters between 2019 and 2022.

FBI director Christopher Wray said the group “made hundreds of millions of dollars in the process — on the backs of thousands of innocent car owners.”

FBI Special Agent Patricia Curran says: “It’s a very easy crime, especially on the street level. It takes less than a minute. If you cut off several a night, you can make thousands of dollars.”

After the high-profile cases, Curran says the agency has heard of some cutters who’ve dropped out, saying it isn’t worth the risk.

Cook County Sheriff Tom Dart and the Illinois Statewide Auto Theft Taskforce announced felony charges in May against a Worth Township man they said had 612 catalytic converters on his property near Palos Heights but no license to buy, sell or recycle them.

Victims’ costs, frustrations

Mary Cowen’s Hyundai Tucson got hit last year in West Ridge, a North Side hot spot for converter thefts.

“They came out at 3:30 a.m., when everybody’s sleeping,” says Cowen, a retired teacher, who didn’t file a police report.

The damage came to about $700, Cowen says, partly covered by insurance.

Cowen’s neighbor James Biancofiori’s 2012 Hyundai Elantra appeared in a video posted by another neighbor on Nextdoor in March. In the video, a dog barks and a car alarm sounds as a crew works to take the catalytic converter.

Biancofiori paid for the $950 repair out of pocket. “I didn’t want my rates to go up,” he says.

Kim Griffin made an insurance claim but still paid a $500 deductible when her 2013 Hyundai Tucson was hit by thieves in the parking lot of Old Orchard Shopping Center in Skokie last November. Griffin, who lives in Andersonville and works for a nonprofit, was working a few part-time hours at a mall store.

“I started my car, and it made this horrible sound,” she says. “It sounded like there was a giant hole in my car.”

The repair took four days, and, Griffin says, “It cost me more money to work that day than I made.”

Rick Garcia’s 2010 Prius got hit at work, too. Garcia, who lives in Edgewater, had parked in front of his office on West Ardmore Avenue last October. Thieves hit between noon and 3 p.m., causing more than $2,500 in damage.

Garcia had a $1,000 insurance deductible and had to pay for Lyft and Uber rides. He was expecting to see his insurance premiums go down when he turned 65, but that didn’t happen after he made the claim.

He posted about it on Facebook and got an avalanche of replies. “Everybody was responding — ‘I got hit two weeks ago.’ ‘I got hit.’ People lose work. People lose time. The individual has all of these expenses that were unexpected from this one act. It piles up.”

Depending on the circumstances, prosecutors can charge suspects with aggravated possession of a stolen vehicle or burglary to an automobile, both more serious offenses than theft, says David Williams, a Cook County state’s attorney’s supervisor.

But Williams says of recovered catalytic converters, “To be able to match it up to the car, except circumstantially, is really difficult.”

Authorities target the buyers

The Illinois General Assembly passed a law that took effect on May 27, 2022, targeting scrap metal buyers to try to cut off the illicit trade. The measure requires metal dealers to keep electronic records of all catalytic converter transactions and bans cash sales for converters over $99.

State Rep. La Shawn Ford, D-Chicago, who sponsored the law, says: “There is a demand for it because there is a demand from the scrap metal industry. They are really part of the problem.”

In July 2022, two months after the law took effect, catalytic converter theft reports in Chicago skyrocketed to their highest point, with 913 that month — up 314% over the previous year’s 291.

The numbers stayed high all last summer and fall — far above a year earlier — and only started dipping slightly this spring.

Broshous says some states have prohibited cash sales of catalytic converters entirely. He thinks having a serial number stamped on each converter, much like a VIN, might dissuade cutters from taking them and make scrappers wary about buying them.

“The real solution for this is going to be at the manufacturer level,” he says.

But the automotive industry says used cars — not new vehicles — are most often targeted, so mandating serial numbers on new converters doesn’t make sense. Some manufacturers have started redesigning cars to make the converters harder to steal.

The Alliance for Automotive Innovation, a car industry group, wants all scrap dealers to be required to record the date of each catalytic converter purchase and get a copy of the seller’s ID, the VIN of the vehicle it came from and a title or bill of sale proving the seller’s right to sell the part.

The International Precious Metals Institute, an industry group, is pushing for a federal licensing requirement for anyone buying or selling catalytic converters. It could be further strengthened by adding anti-money laundering and “know your customer” rules like banks must abide by, says the group’s Steve Contreras.

Another industry group, the Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries, is pushing a free service, ScrapTheftAlert.com, which lets police list metal thefts in their jurisdictions. Recyclers can check that the metals they’re buying aren’t on the list.

The free service has recovered about $3.3 million in stolen metal, including car parts, copper, brass and other metals, says Todd Foreman, a former police chief in Virginia and the group’s law enforcement outreach director.

Vehicle owners have tried painting their converters pink or stenciling numbers or words on their devices in an effort at deterring thefts.

Ambrosio “Red” Montaño, who manages Value Plus Mufflers at 4321 N. Western Ave. in North Center, says most thieves aren’t stopped by pink paint. Worse, he says, some car owners who’ve installed clamps with metal cables on their converters end up with worse damage: Instead of sawing off just the converter, thieves will cut a much bigger section and take the converter, the clamp and nearby oxygen sensors.

Montaño says a better way to protect the converter is to install a large metal shield over the entire area. These are sold online for $100 and up, customized for different vehicles and installed at auto shops.

“It’s a lot more work for them to cut around,” he says. “So they’ll just go to the next car that doesn’t have a shield.”

Contributing: Frank Main, Jesse Howe