The split-fingered fastball fairly winked at Aaron Judge as it passed his field of vision. Judge did not fall for its false charm. He watched this changeup disguised as a fastball from Red Sox pitcher Nathan Eovaldi tumble ever so slightly below the outside corner of home plate. Ball one.

That Aug. 12 pitch might have been just another one of the 12,593 pitches Judge had seen to that point in his career with the Yankees, including 104 from Eovaldi, except for what happened next. What no one saw ranked at least as amazing as the unmistakable percussive punishment Judge delivered to the next pitch. It was the advanced calculus known by only an elite hitter—part homework, part intuition, part pattern recognition from those 12,000 pitches. It is the reason Judge is chasing home run history.

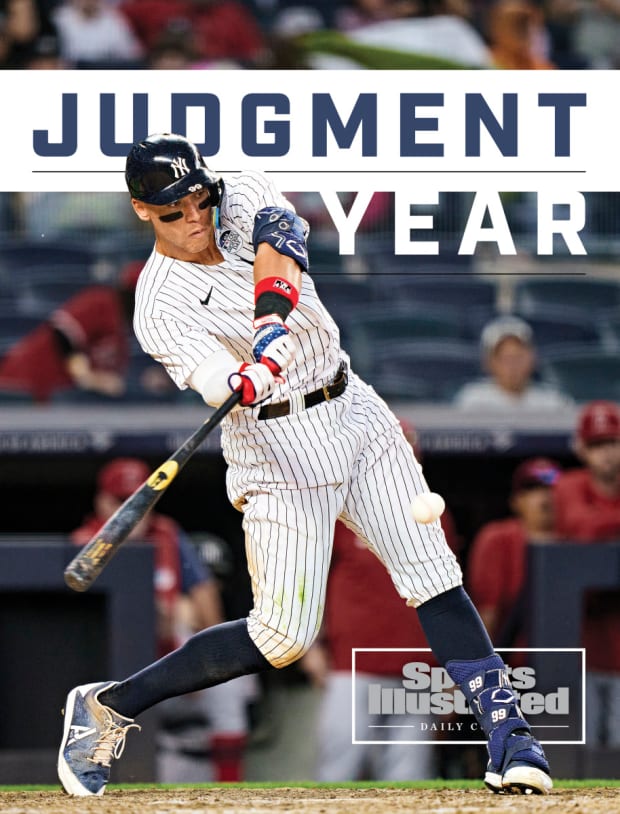

Erick W. Rasco/Sports Illustrated

“Eovaldi—and even the Red Sox in general—they like to throw me up and in with the heater,” Judge says. “They [first] like to stay with stuff soft away. Soft away, down and away, down and away . . . see if they can steal an early strike. And then they always like to come back in and get me a little off balance and make me be conscious of it so they can go back to that away pitch.

“So when they went with a splitter down and away for a ball, I just had a feeling. O.K., I don’t think they want to go down there again to go 2–0 on me. They might try to come up and in here and . . .

“It kind of worked out.”

Judge smiles at his own litotes. Eovaldi threw an up-and-in fastball directly where catcher Kevin Plawecki set the target—and precisely where Judge expected the pitch. He hit it 113.8 miles per hour, harder than any ball hit all season by any right-handed hitter on an up-and-in fastball. It soared completely out of Fenway Park, landing atop a parking garage across the street. Eovaldi remained in a state of amazement after the game, telling reporters, “It’s just, he’s on fire right now. He’s locked in at the plate. I felt like I located that pitch.”

The blast gave Judge 46 home runs through 113 team games, a pace matched by only Barry Bonds in 2001 (48, on his way to a record 73) and Babe Ruth (46 in 1921, on his way to 59 in a 154-game season). No player has hit 60 home runs since MLB began testing for steroids in ’03. And no American League player has come within three of the league record of 61 since Roger Maris set it in ’61. Judge enters Tuesday with 55 home runs in 141 team games, a pace of 63 for a full season.

“Seventy-three is the record,” Judge says. “In my book. No matter what people want to say about that era of baseball, for me, they went out there and hit 73 homers and 70 homers, and that to me is what the record is. The AL record is 61, so that is one I can kind of try to go after. If it happens, it happens. If it doesn’t, it’s been a fun year so far.”

Where Judge’s bat met Eovaldi’s fastball is the preeminent metaphor for this Year of Judge. It is a moment in time and space where a hitter executes his craft in a way that is, as the writer Dan Jenkins defined it in golfing terms, dead solid perfect. The intersection of a round bat traveling 85 miles per hour and a round ball traveling 93 miles per hour occurs about 12 to 18 inches in front of home plate in an impact area of about 12 square centimeters—opposing forces colliding in a window the size of three postage stamps. No one creates this perfect convergence, known as “barrels” when done at optimum force and angle, more than Judge.

This season is defined by the intersection of forces in Judge’s career. Of the wisdom gleaned from those 12,000 pitches. Of the Yankees’ offering him a contract extension of $213.5 million just before Opening Day and then, to his disappointment, going public with the terms of it after he turned it down. Of his impending free agency. Of the advice he received from a former teammate about how to protect what had been his injury-prone body. Of accomplishing by July 28 the one goal this year that makes him proudest—and has nothing to do with hitting home runs.

The simplistic narrative is that Judge “bet on himself” by turning down $213.5 million. He does not see it that way. “It was never a gamble for me, because no matter whether we got a deal done or didn’t get a deal done I was still going to be playing with the Yankees this year,” he says. “In my mind there was no gamble. I’ll be playing for the Yankees, working as hard as I can to help us win a World Series. All that other stuff, that’s why I’ve got an agent.”

Erick W. Rasco/Sports Illustrated

As did Marcus Aurelius, Mark Twain and Joan Didion, Aaron Judge keeps a notebook. It used to be a physical notebook, but when he found carrying it around to be a bit of a pain, he switched to keeping a digital version on his phone. He will log key swing thoughts from his personal hitting coach and how he felt at the plate during especially good games.

Each time he opens his digital notebook, the first page greets him with a reminder: “.179.” That was Judge’s batting average in 2016, when he struck out in 44% of his trips to the plate during a late-season call-up. After overhauling his swing that winter, Judge hit a rookie-record 52 home runs the next season. After that he took a black marker and wrote “.179” in his size-17 spikes to remind himself of the struggle. He has since moved the numerical reminder from his shoes to the title page of his notebook. “Still glaring at me right at the top is ‘.179,’ ” he says. “No matter how many homers, what’s going on, or we’re in first place, I know it can change in the blink of an eye.”

Hitting, it turns out, is a bit like how Didion described writing: “an attempt to find out what matters, to find the pattern in disorder, to find the grammar in the shimmer.”

Despite those 52 homers in 2017, Judge struggled in other ways to find the pattern in the disorder that pitchers presented him. That season he struck out 50 times flailing at breaking pitches out of the zone—fourth-most in the majors. He hit .224 on breaking pitches over his first five seasons. He watched too many hittable pitches go by early in counts.

Moreover, injuries wracked his 6' 7", 282-pound body. He missed 37% of the Yankees’ games from 2018 through ’20. He suffered a broken wrist in ’18. An oblique strain in ’19. A cracked rib and collapsed lung in ’20. It was after Judge returned in ’19 from the oblique strain that veteran teammate Edwin Encarnación pulled him aside after a game. Encarnación noticed how often Judge would hit in the indoor batting cage, even during games.

“If I struck out, I’d be in the cage,” Judge says. “Hitting, hitting, hitting. If my swing didn’t feel right, I’d be back in the cage. In-game hitting, pregame hitting, postgame hitting.”

Encarnación told him, “All those swings you’re taking? It’s making you tired and it’s going to get you hurt. And all you are doing is practicing bad swings. You don’t need to take a thousand swings. You just need to take a couple and go out and play. Less is more.”

“When he told me that,” Judge says, “I was like, Less is more? What’s he talking about? Once I started learning that I was like, O.K., that’s probably why I’m blowing out certain muscles.

“I started watching veteran guys. I watched DJ LeMahieu. He’ll go in and take five swings off the tee, five flips, and go out there in the game and go 3-for-4. And that was a lesson for me. It’s quality over quantity. It’s helped me out the past two years especially.”

Entering Tuesday, Judge has played in 94% of the Yankees’ games over the past two years. He prepares for games now by taking “a couple” of swings off the tee; a few more off flips; a few more off “short BP,” in which the pitcher stands only about 40 feet away; and a few more against a high-velocity machine that spits out fastballs at 110 miles per hour as well as nasty, high-spin sliders. Judge also will simply track the pitches without swinging so that his eyes grow accustomed to more velocity than he will see later.

“So when I step out there in a game it’s Oh, that’s all this guy has?” Judge says. “I saw that a hundred times already.”

He also has incorporated postgame maintenance work for his body, including stretching exercises, hot and cold tub therapy sessions, and saunas.

“I do all my recovery stuff, which you don’t think about when you’re 24 or 25,” he says. “You just think, I played my game. I’m going to eat, go back to bed and I’ll wake up feeling great. Now it’s the little things, even if it’s 20 minutes after the game of stretching.”

Judge hit a career-high .287 last season. He cut his strikeout rate to a career low (25%). He finished fourth in MVP voting. He wanted more. Soon after the season ended, he reported to the Yankees’ training complex in Tampa and worked with one of the team’s speed trainers.

“I said, ‘Hey, I see guys in the minor leagues with 40 stolen bases and I know I’m faster than that guy. What can I learn from you?’ ” Judge says.

They broke down his running form and studied how to get a better first step. If there is a definitive story about what motivates Judge, this is it. Almost immediately after hitting 39 homers and slugging .544, the biggest position player in baseball history went to the minor league camp to become a better base runner.

“Especially hitting higher in the lineup,” says Judge, who usually bats second, “if I can get on base and I can get into scoring position or even have that threat to the pitcher that I might steal, [the guys] behind me might get better pitches to hit.”

Judge currently leads the majors in runs (113), home runs (55), RBIs (121) and total bases (343), which has been done by only Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Ted Williams and Mickey Mantle since RBIs became official in 1920. But ask him which part of his season brings him the most pride, and Judge—who has swiped 16 bases in 18 tries, nearly three times as many as any other player 6' 7" or taller in history—has a simple answer: “Stolen bases.”

Wendell Cruz/USA TODAY Sports

The Yankees offered Judge $30.5 million a year. Eleven players earn more, including two on his own team. (The Yankees will be paying Gerrit Cole and Giancarlo Stanton more over the next six years.) They made the proposal just before Judge’s deadline to get a deal done by Opening Day. Immediately after Judge’s rejection, New York GM Brian Cashman announced the terms of the offer in a press conference for the sake of transparency. Judge did not appreciate such candor.

“I could have taken it out on the organization and taken it out on the fan base and taken it out on my teammates,” Judge says. “But I kind of turned it into a positive. Like, ‘Hey, we didn’t get it done. Now I can turn my focus back to the season and do what I can do to help this team win as many games as we can.’ That’s what I decided to do.”

“Nothing fazes him,” says Yankees first baseman Anthony Rizzo. “You don’t know if he’s 4-for-4 with four homers or 0-for-4 with four strikeouts. That’s amazing, because he carries the whole weight of being the face of the franchise. I think just how he’s handled himself this year, with all the quote-unquote noise, turning down the money, that being made public—what he turned down—and just going out and producing every day is amazing.”

Cole, when asked to identify Judge’s best trait, says, “The even keel. I wish you could see him some days when he’s DHing. He’s so loose. We’re hanging out on the couch watching the game on TV and talking about the game, and when it’s his turn for another at bat he gets up off the couch and goes out and hits another home run.”

This is the intersection. All roads led here. The .179. The $213.5 million. The 12,000 pitches.

“A lot of the work he’s done up to this point, not just this year, it’s showing itself,” Yankees hitting coach Dillon Lawson says. “His ability to handle more types of pitches is most impressive. It’s having the information and now being able to use it because he’s more skilled. Maybe the most impressive thing is he’s found a way to improve without going outside of his strengths. Guys with power typically have to lose some power to gain more contact. He’s kept it.”

Judge leads the majors in slugging against both fastballs (.767) and breaking pitches (.700). He’s hit 18 of his first 55 homers off breaking pitches; his previous high was eight. He has had more hits off the first or second pitch of an at bat (53) than in any season of his career, a testament to his preparation and intuition.

This historic season is happening at a time when it has never been more difficult to hit since the mound was lowered in 1969. (The overall MLB batting average is .244, which would be the fourth-lowest since 1900.) Four-seam fastballs are averaging 93.9 miles per hour, an all-time high and fully two miles an hour faster than just 14 years ago. The number of pitches clocked at 100 mph and faster has more than doubled from only three years ago. Sliders are spinning 322 RPMs faster than they were seven years ago.

If all that did not make for a difficult enough hitting environment, Judge’s height creates problems for umpires calling low pitches against him. From the start of 2017 through Sunday, Judge had 315 pitches below the zone miscalled as strikes—21.6% more than any other hitter. Judge bears such treatment with little protest. “He told me hasn’t been thrown out of a game here or in the minor leagues,” Lawson says. “His temperament plays into his consistency.”

Having such a big strike zone can be a vulnerability, but, says teammate Josh Donaldson, “He controls the strike zone really well. I remember I talked to Nelson Cruz in Minnesota, another guy with long arms. They have to focus on staying tight with their movements. If their arms get away from their body at all they get jammed. Judge understands really well the effort level he needs to produce a quality swing.”

“I know this: Preparing to face Judge is a lot different now,” says Kyle Snyder, the Rays’ pitching coach. “It’s harder. He covers so many more pitches.” Through 19 meetings this year, covering 55 pitches, the Rays threw Judge only 16.9% fastballs, including only 13 high fastballs in the zone.

“I love the little chess match that some people don’t see from the outside between the batter and pitcher,” Judge says. “Why certain pitches are thrown. Why guys swing at certain pitches. The different situations in a game that come up always intrigued me as a kid.

“Now, it’s a lot of late nights of video, watching past at bats, watching guys similar to me and how they pitched against them in recent outings. It’s also not being afraid to take the chance and knowing I’ve done my homework. Now it’s just go out there, recognize the pitch and do damage.”

Judge had never faced Royals right-handed reliever Jackson Kowar before he stepped in with the bases loaded July 29. Kowar throws his changeup to right-handed batters more often on first pitches (48%) than he does later in the at bat (38%). Kowar threw a changeup first pitch. Judge was ready for it. He smashed it for a grand slam.

“He is great at how to apply his mechanics based on what the pitcher is doing,” Lawson says. “How do I apply it against a stock pitcher? A guy with ride? A guy with sink? A slider monster? He has shown me he has a skill set and truly refined it. It looks really simple. But if you’re not at the point he is in his career you can’t do this stuff.

“It’s like what people say about overnight success. You don’t know the years of work that went into it. This has been years of work in the making.”

Erick W. Rasco/Sports Illustrated

This is what happens when a hitter discovers the pattern in disorder, the grammar in the shimmer. The exquisitely crafted sentence and the swing against the 0–1 Eovaldi fastball are so perfect as to belie the toil that made such beauty possible. What is genius if not the camouflage of effort?

“The gamesmanship,” Cole says, “is where he continues to get better. He takes pitches out of a pitcher’s pocket. He did it to [Mets ace Max] Scherzer. Max fired 97 up and in. Dotted it up. And he spoiled it. The fact that Max hadn’t thrown 97 all game and the fact that Aaron hadn’t seen a fastball in like an hour and 45 minutes made it amazing.”

Ask Judge how he wants this season to end, and he will talk about not his final tally of home runs, but whether the Yankees will win the World Series. “I want to be a World Series champion,” he says. “Not only once, but twice, three times if I can—as many times as I get a chance.”

There is something else he wants. This wish of his is apparent on the television monitors that hang from the ceiling of the Yankees’ clubhouse. They are in full view from Judge’s locker. On an August afternoon he can see the faces of Little Leaguers, which are the faces of hope, looking for someone or something to follow. He is moved to hear how many of them regard Aaron Judge as their favorite player, and how many of them wear his number.

“It really hit me the type of impact I’ve had when I started seeing Little Leaguers wearing 99,” he says. “I didn’t see too many 99s when I was growing up. I saw a lot of number 2s, but not too many 99s.

“Seeing that, and seeing this little kid in Kentucky, or in New York, in Florida, in California . . . they’re watching every single thing you do. Every little thing you say. It puts it in perspective. Do the right things, play the game the right way and hopefully you inspire one of those kids to do the right thing in 10, 15 years when they’re in your spot.”

This is his season in the shimmer. How it ends is yet to be written—the number of home runs he hits, whether the Yankees win the last game of the year, the final number and payer of his next contract. But what he already has achieved is an equilibrium in his career, a soundness of body and mind that is behind a historic season. In this way, too, he resembles Marcus Aurelius, the Stoic known as the last of the Five Good Emperors of Rome, who one day pulled out his notebook and wrote, “Give your heart to the trade you have learnt, and draw refreshment from it.”