Now in its tenth year, the Stella Prize – founded as a reaction to the under-representation of women in Australian literary culture – has been a force for change. As conversations about representation continue to evolve, the prize does too.

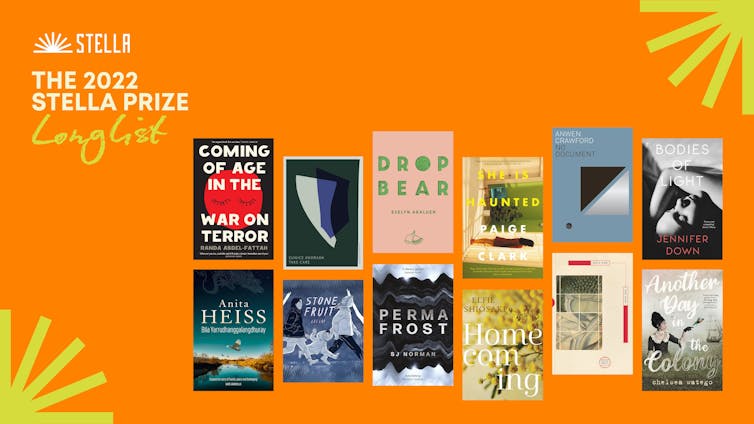

This year’s longlist, just announced, reflects those conversations.

For example, five of the 12 longlisted writers are Indigenous. One writer is non-binary (the first non-binary writer to be recognised was just last year). And in the first year that poetry is eligible, there are three poetry collections (plus one hybrid collection). Overall, it’s a longlist that adventurously moves across genres.

The prize continues to recognise new and younger writers: seven of the longlisted titles are first books.

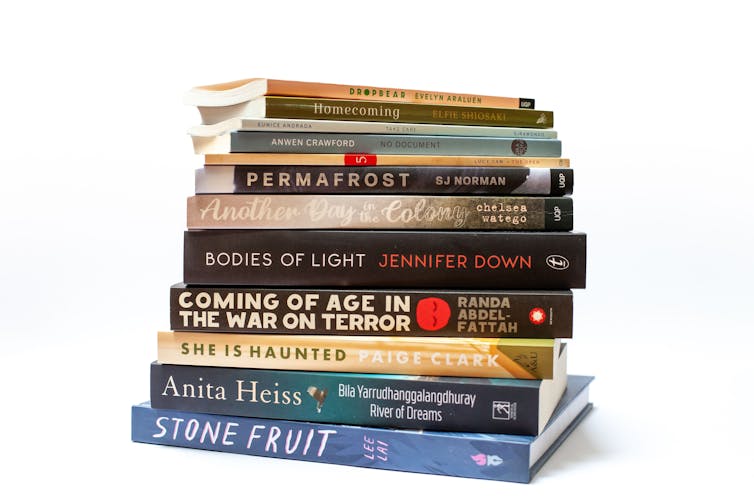

The 2022 Stella Prize longlist is:

Coming of Age in the War on Terror by Randa Abdel-Fattah (New South Books)

TAKE CARE by Eunice Andrada (Giramondo Publishing)

Dropbear by Evelyn Araluen (University of Queensland Press)

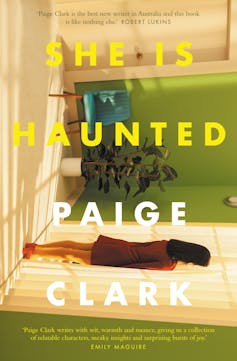

She is Haunted by Paige Clark (Allen & Unwin)

No Document by Anwen Crawford (Giramondo Publishing)

Bodies of Light by Jennifer Down (Text Publishing)

Bila Yarrudhanggalangdhuray by Anita Heiss (Simon & Schuster)

Stone Fruit by Lee Lai (Fantagraphics)

Permafrost by S.J. Norman (University of Queensland Press)

Homecoming by Elfie Shiosaki (Magabala Books)

The Open by Lucy Van (Cordite Books)

Another Day in the Colony by Chelsea Watego (University of Queensland Press)

Life-changing win means inclusion is important

For a writer, winning the Stella Prize is an economic and symbolic bonanza, guaranteeing sales, prestige, $A50,000 in prize money, and an associated stream of income from book tours and festivals.

After winning the Stella Prize last year for her novel The Bass Rock, Evie Wyld said that even the money she had received for her longlisting ($1000) and shortlisting ($2000) helped her to survive during a time of pandemic and lockdowns.

“It really [did] mean that I don’t have to look for work elsewhere and so I can get on with writing”.

The stakes of the win make questions of inclusion – and who can benefit from the opportunities offered by the prize – especially important.

Nine of ten Miles Franklin winners have been women since the Stella Prize launched

The Stella Prize was created in 2012, as a response to all-male shortlists for the Miles Franklin Award in 2009 and 2011. The Miles Franklin Award had been dominated by male writers since its inception in 1957.

Since the Stella Prize began, nine of the past ten Miles Franklin Award winners have been women. In 2013, the year after the first Stella Prize was awarded, the Miles Franklin shortlist was all women for the first time.

Since 2016, five of the six winners of the Victorian Premier’s Prize for Fiction and the Christina Stead Prize for Fiction (one of the New South Wales Premier’s Literary Awards) have been women.

Gender gap continues – except in poetry

A 2020 study found a continuing gender gap in the New South Wales Premier’s Literary Awards (1979-2015), the Victorian Premier’s Literary Awards (1985-2015), and the Miles Franklin Award (1965-2015), except in the genre of poetry.

It discovered that women were 29% of the Miles Franklin Award winners and 30% of winners of the Victorian Premier’s Literary Award for Fiction.

Figures for other prizes were 39% for the Christina Stead Prize for Fiction, 30% for the Victorian Premier’s Literary Award for Non-Fiction, 36% for the Douglas Stewart Prize for Non-Fiction, and 48% for the Kenneth Slessor Prize for Poetry.

The Victorian Premier’s Literary Prize for Poetry was the only prize where the majority of the winners were women (53%).

Criticisms: overwhelming whiteness and calls for attention to diversity

Prizes for women’s writing are sometimes criticised for hiving off women’s writing, or somehow marking it as secondary to that of their male contemporaries. These arguments seem to assume that prizes exist in a bubble, ignoring the surrounding power structures that shape the literary field.

The Stella Prize has also been criticised for the whiteness of its longlist choices. Alexis Wright is the only writer of colour to be awarded the prize, for Tracker in 2018.

While the Stella Prize is the organisation’s best known initiative, it also generates school resources and events, and its Stella Count surveys the extent of gender bias in book reviews.

The Stella Count has helped to close the gender gap in book reviewing, but has been criticised for not including authors who are non-binary and for not considering diversity.

Genre, marginalisation and cultural value

Feminist approaches to Australian literature have often overlooked genre as an issue. Yet the marginalisation or exclusion of particular genres in criticism and literary prizes influences how different kinds of literature are culturally valued.

Three poetry books are longlisted this year: Eunice Andrada’s TAKE CARE, Evelyn Araluen’s Drop Bear and Lucy Van’s The Open. Yet the longlist foregrounds the limits of generic categories. Araluen and Van’s collections include prose poetry, and Elfie Shiosaki’s hyrbid collection, Homecoming, draws together poetry, prose and the colonial archive to tell family stories that have been historically positioned outside literature. Anwen Crawford’s No Document blends the essay with lyric, and makes use of blank space to meditate on ephemeral art practice and lost friendship.

The longlist also includes a graphic novel. Lee Lai’s Stone Fruit contrasts the joy within a chosen queer family with the difficulties that emerge when trying to navigate older family ties and lack of acceptance.

Many longlisted works are hybrid in form, conveying complex ideas and feelings. Randa Abdel-Fattah’s Coming of Age in the War on Terror draws together memoir, historical record, and interviews to explore the impact of Islamophobia on the generation of children after 9/11.

Calling out colonial violence

The five Indigenous writers on the longlist share a focus on intergenerational memory, calling out colonialism’s ongoing violence.

Chelsea Watego is scathing about a discourse of hope, instead proposing a life of sovereignty, activism and joy. Evelyn Araluen casts a sharp eye over the racism of early children’s literature and the settler-colonial myths and desires that shape suburbia and poetry. Anita Heiss celebrates Wiradyuri language in her historical novel, which revisits Wiradyuri bravery during the 1852 flood of Gundagai.

Thinking beyond Australia

Many of the longlisted writers explore how histories continue to shape places and everyday life.

Lucy Van’s long poems meditate on aspects of familiarity, privacy and security. Indigneous writer S.J. Norman considers how ghosts haunt the contemporary consciousness at sites of past trauma. Paige Clark examines how young women of colour navigate expectations that come from within the family as much as without, and sometimes surreal strategies used to cope with vulnerability. Eunice Andrada explores how sexualised violence intersects with racism in war crimes, rape culture, harassment, and stereotypes.

Stella and Miles

Literary prizes operate in a shared ecology. Yes, the Stella Prize has significantly influenced the Miles Franklin Award, whose founder (Stella Maria Miles Franklin) it was named for. But the Stella Prize has also benefited from that prize’s authority.

Alexis Wright received a Miles Franklin Award eleven years before her Stella Prize. Evie Wyld also won the Miles Franklin Award, with All the Birds, Singing, seven years before her Stella win. This year’s chair of the Stella Prize, Melissa Lucashenko, was the 2019 Miles Franklin Award winner for Too Much Lip. South African activist Sisonke Msimang was on the judging panel for both the 2021 Miles Franklin Award and the 2022 Stella Prize. Melinda Harvey, co-leader of the 2018 Stella Count, was a judge of the Miles Franklin Award from 2017 to 2021.

While such overlaps suggest a decreasing distinction between the two prizes, their missions are distinctly different. The Miles Franklin is guided by its founder’s desire to annually reward “a novel of the highest literary merit that presents Australian life in any of its phases”.

The Stella Prize’s mission is “to promote Australian women’s writing, support greater participation in the world of books, and create a more equitable and vibrant national culture”.

It is inherently about change – as reflected in the 2022 longlist.

Ann Vickery does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.