Hailing from the desert city of Agadez in Niger, Mdou Moctar is a genuine trailblazer. With a sound that bridges the ancient traditions of the Sahara and the electrifying energy of modern rock, his journey as a musician is a tale of evolution and experimentation, a relentless pursuit of new sonic frontiers. And yet, for all his open-mindedness as an artist, he believes that the key to creating original music is to shut himself off from the world.

“I still focus on my own work rather than getting inspiration from other guitarists,” he tells Total Guitar, speaking in French through an interpreter. “I even take long breaks from playing guitar to let something new germinate.”

In 2021, his breakout release Afrique Victime was acclaimed by TG as the guitar album of the year. Now comes his most potent and provocative work to date: Funeral For Justice. Recorded in just five days in a largely unfurnished house in upstate New York, the album captures Mdou and his band at their most primal and unrestrained. The music surges with punk energy and scorched-earth guitar heroics.

Mdou’s professional musical journey began with his 2008 album Anar, on which he paired the acoustic guitar traditions of the Tuareg people with the futuristic sheen of Auto-Tune. His music spread via Bluetooth swaps of digital files from his cassette recordings, a common practice in the region.

This grassroots distribution method highlighted his initial challenges in reaching a wider audience, but also showcased the communal and innovative spirit of his music.

Eventually Mdou’s music found its way to Christopher Kirkley, founder of the Sahel Sounds label. He became such a fan he featured Mdou on his influential compilation series, Music From Saharan Cellphones. This amplified the young musician’s reach and introduced him to a global audience hungry for fresh, boundary-pushing sounds. Kirkley went on to cast Mdou as the main actor in Akounak Tedalat Taha Tazoughai, a Tamasheq language interpretation of Prince’s Purple Rain.

Emboldened by his growing fanbase, Mdou continued to evolve and refine his craft. His 2013 follow-up album Afelan saw him delving deeper into the well of Tuareg music, with a mix of traditional acoustic music, and blistering, psychedelic desert blues, simultaneously showcasing his growing mastery of the guitar.

His music has continued to develop through live work and album releases, as he’s harnessed his cutting tone and expressive range to channel the raw power and emotional intensity of his songwriting.

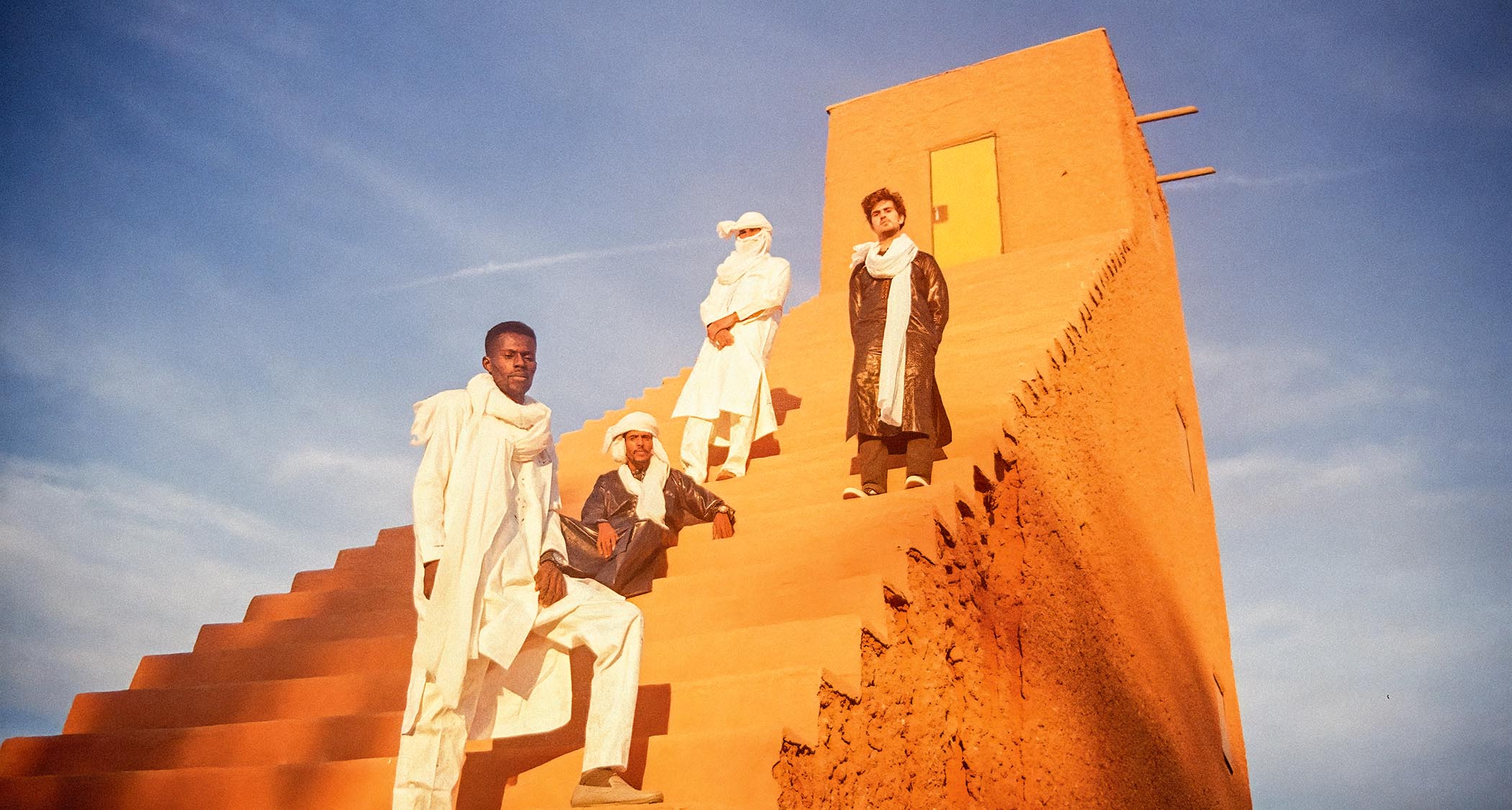

The sound of Funeral For Justice is even rawer and heavier than previous recordings, created by Mdou with rhythm guitarist Ahmoudou Madassane, drummer Souleymane Ibrahim, and American bassist/producer Mikey Coltun. The band’s energy stems from their beginnings, playing all-night shows at weddings back home, where amps were cranked to the max and entire towns joined in the revelry.

But although the roots of Mdou’s music remain firmly in the Tuareg tradition, the branches now stretch in startling new directions. As Coltun says: “I grew up in the D.C. punk scene and this is no different. It’s a DIY punk show. People bring generators, they crank their amps. Things are broken, but they make it work.” That communal spirit now infuses their stage shows around the world, with Mdou’s ecstatic, high-velocity guitar playing sending crowds into a frenzy.

For many artists, retaining the raw energy and spontaneity of a live performance in the controlled environment of a recording studio can be a daunting task. The thrill of feeding off an audience’s reaction, the adrenaline rush of improvisation, and the organic interplay between band members can be difficult to replicate when the red light is on and the clock is ticking.

In the studio, we make sure we’re feeling well, able to do it our way, and not be bothered by technicalities. We pick a time when we’re determined and know what we want to record

It’s a challenge that has plagued musicians across genres and generations, from the early days of rock ’n’ roll to the present. But for Mdou and his band, the key to bridging this gap lies in a combination of preparation, mindset, and imagination.

“We don’t record albums as most people do,” Mdou says. “We have a really personalised system, and the way we play in the studio is just like live. We don’t use a metronome, or precisely time anything. And this was recorded after a tour, so we had the touring energy still in us. We give ourselves room to play the way we want to play.”

When we ask him how they go about capturing their electrifying live sound in the studio, he responds with a mixture of pragmatism and poetry. “It’s a question of work and practice. In the studio, we make sure we’re feeling well, able to do it our way, and not be bothered by technicalities. We pick a time when we’re determined and know what we want to record. It’s like a union between the band members. We imagine an audience and express joy.”

Mdou’s unique guitar style is a testament to this joy, his unwavering passion for music, and his ability to overcome obstacles. Growing up in a conservative Muslim family in the Sahara Desert, he faced disapproval and limited resources in his pursuit of mastering the guitar. However, his resilience and determination led him to forge his own path.

His journey as a self-taught musician began at the tender age of 12, when he first witnessed a mesmerising street performance by desert blues pioneer Abdallah Ag Oumbadougou. Inspired by the raw power and emotion of Oumbadougou’s playing, Moctar set out to learn the guitar by any means necessary. With no access to a proper instrument, he crafted his own makeshift guitar using a wooden plank and bicycle brake cables.

As Mdou honed his skills, he began to absorb the rich musical traditions of his Tuareg heritage while immersing himself in the sounds of Western rock legends like Jimi Hendrix, Eddie Van Halen and Prince. Yet despite these diverse influences, Mdou’s style remains firmly his own.

“I can’t say I was ever majorly influenced by other guitar players,” he says. “I like creating in a very personal way. I learned music a lot by ear, especially when I started very young. Before discovering certain helpful instruments and meeting other artists, I used my own personal instrument settings and tunings.”

His left-handed playing technique is certainly unique and adaptive, shifting seamlessly from soft acoustic passages to intense electric guitar. This dynamic range reflects both his traditional roots and his modern experimental urges.

“My technique has definitely changed, and there are a lot of new things on this album. Like on Oh France, which was the hardest on the album because the rhythm is tricky, and the track Takoba.”

Asked about this learning process, and how he picked up the scales and chords he uses, he replies: “I do it by ear. I was alone when I started, so I did it all by ear before discovering instruments that helped me, and figuring out how to tune them, and meeting other artists. Different songs use different, very particular tunings.”

That must make it hard for Western musicians to learn his style, we ponder.

“It’s my own personal tunings,” he says. “I would need to show you exactly how to tune your guitar for you to be able to play it the same.

“Most songs I play are traditional, so it doesn’t fit well into Western music theory. Even at home, some people have trouble if I don’t show them exactly how to tune it. Young guitarists who try to copy me tell me that regularly.”

I do it by ear. I was alone when I started, so I did it all by ear before discovering instruments that helped me, and figuring out how to tune them, and meeting other artists

Mdou’s guitar solos on the new album have also reached new heights of technical prowess and emotional intensity. Using a barrage of rapid hammer-ons and pull-offs on open strings, he unleashes surging melodies and countermelodies that seem to channel the intensity of the desert landscape.

At once primal and otherworldly, his solos present a kind of psychedelic ‘desert shred’ that marries dazzling technical ability with an almost trance-like sense of abandon. “Yes, I feel there is a lot of evolution in my solos,” he says. “On this album, we were given the freedom to record it exactly how we wanted.”

Having broken down boundaries between African music and Western rock, does he consider incorporating styles like jazz or blues into his music?

“The problem is I don’t really know those different styles well, since I never went to music school or had formal guitar lessons,” he explains. “But if I hear something I like, I’m curious to see how my style would sound with that rhythm or instrument. I want to experiment. When I was younger I tried electro instruments to see what Tuareg music would sound like that way. I will remain curious.”

Mdou’s journey from crafting his own makeshift guitar to wielding a Fender Stratocaster is a powerful symbol of his musical evolution and the challenges he’s overcome along the way. As a left-handed player in a region where southpaw guitars were virtually nonexistent, Moctar faced significant hurdles in his musical development.

“The hardest thing for me was being left-handed in a place with no left-handed guitars,” he recalls. “To this day, I’m the only local person I know with a lefty guitar. Left-handed people have to use right-hand guitars upside down, which is very difficult. As a kid, I couldn’t join in and play with friends. I could only watch. That was a hurdle.”

The acquisition of his white left-handed Stratocaster marked a turning point in his musical journey, enabling him to fully express his creative vision. “When I learned lefty guitars existed, it really impacted me,” he reflects. “I used the same white guitar with the same effects on this album,” he says of his Stratocaster. “I tell Mikey what sound I’m going for, and he sets it up for me.”

This partnership between artist and instrument is evident throughout Funeral For Justice, with Mdou’s Stratocaster serving as an extension of his musical voice. The guitar’s cutting tone and expressive range are the perfect vehicles for his searing leads and hypnotic rhythms, allowing him to channel the raw energy and emotion of his live performances into the studio recordings.

But amid the blazing riffs and pummelling rhythms, there is also a profound sense of purpose. The new political and social themes apparent on this album have infused the music with a distinct energy. The lyrics, sung in Mdou’s native Tamasheq language, address the plight of the Tuareg people and the postcolonial struggles of Niger with bracing clarity and righteous fury.

Asked how he composed these powerful anthems, and whether the lyrics inspired him towards a heavier sound, he replies: “Sometimes the music comes first, sometimes the rhythm, and then you find lyrics to fit. But in the case of Oh France, the lyrics came first.”

On the track Imouhar, Mdou urges the preservation of the endangered Tamasheq language, being one of the few in his community who can write it. “People here are just using French,” he laments. “They’re starting to forget their own language. We feel like in a hundred years no one will speak good Tamasheq, and that’s so scary for us.”

Just as Funeral For Justice was completed, Niger fell into political turmoil, as a coup ousted the country’s democratically elected government. With their homeland descending into uncertainty, Mdou Moctar’s music feels all the more vital and defiant. “I don’t support the coup,” he states plainly, “but I never in my life liked France in my country. We want to be free. We need to smile, you understand?”

In Mdou Moctar’s hands, the electric guitar becomes a weapon of liberation, a tool to unite people in the fight against oppression while celebrating the undeniable joy of rock and roll communion. Funeral For Justice is both a lament for the fallen and a raised fist for the future – the fearless sound of Mdou Moctar seizing the moment.

- Funeral for Justice is out now via Matador.

.jpg?w=600)