Duane Eddy, who died April 30 at age 86, was the first rock ’n’ roll guitar hero. His unique twangy guitar lines were among the most truly distinctive sounds in the history of rock guitar; whenever producers wanted that unique vibe on a record, they’d only have to ask for a Duane Eddy-style guitar part, and everyone would instantly know what was required.

Unlike anything that had come before him, Eddy – with his echo-drenched, deep-bass driven melodies – managed to encapsulate the essence of the new age of rock ’n’ roll that was taking over the world in the Fifties.

Born April 26, 1938, in Corning, New York, Eddy picked up the guitar at age five and moved to Arizona with his family in his early teens. When he was 16, he started to play in local bars, where he met Lee Hazlewood, the singer, songwriter, and producer who would go on to co-write and produce the majority of Eddy’s hits.

Hazlewood had heard Eddy playing bluegrass in a duo with Jimmy Dell and took them into the studio to cut two sides that he’d written, Soda Fountain Girl and I Want Some Lovin’ Baby, which Hazlewood released on his own label, Eb X. Preston. The record was a flop, but Eddy continued to work with Hazlewood, who managed to score a national hit in 1956 with The Fool, a song he co-wrote (with Naomi Ford) and produced for Sanford Clark.

The following year was a big one for Eddy. First, he made a crucial change in his guitar of choice.

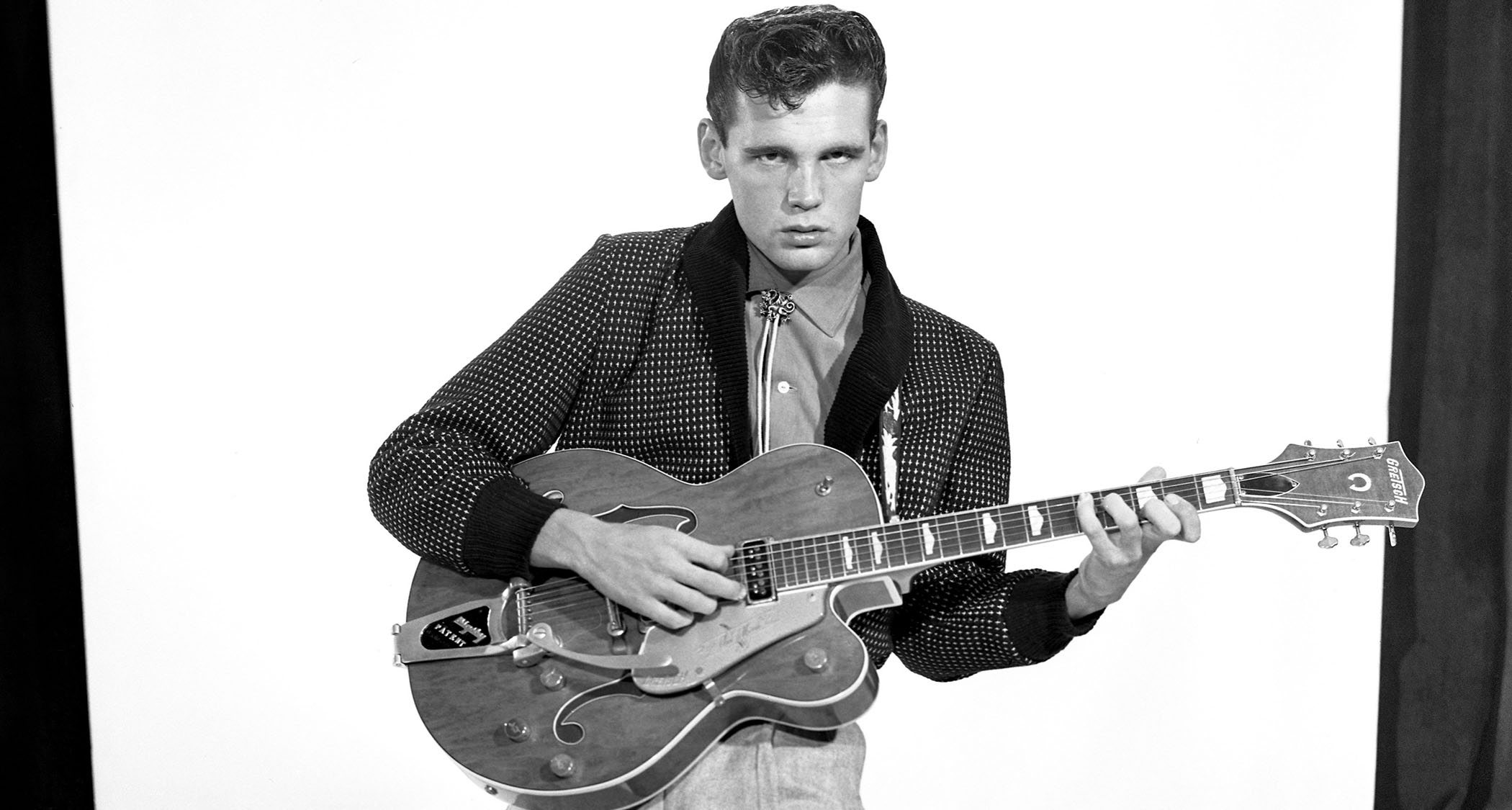

“I knew I really wanted a guitar with a vibrato arm,” he told me. “I traded my Les Paul for a Gretsch 6120 at Ziggie’s Music in Phoenix. That was the key to everything that was to follow. I could hear what I wanted my guitar to sound like in my head, and now I could actually translate it into music.”

Eddy moved to Phoenix that same year, where he rented an apartment from Hazlewood. Bill Justis had a big hit with Raunchy, the instrumental tune that inspired Hazlewood to suggest that Eddy should write his own instrumentals. The result was Movin’ ‘N’ Groovin’, which earned Eddy his first hit, reaching Number 72 on the Billboard chart.

Eddy would tour up and down the States on Dick Clark’s rock ’n’ roll package tours. What most people might not know is that whenever the bus driver got tired, Eddy would take over

With his foot firmly in the door, there was no looking back for Eddy. The follow-up, Rebel-’Rouser, gave him the first of many million sellers and established the quintessential twangy guitar sound that became his calling card.

“I knew we’d hit on something special,” Eddy said. “I couldn’t really sing that well, so I knew that if I wanted to express myself, it was going to have to be through the guitar, and those real low notes just seemed to hit the spot. I cut Rebel-’Rouser with my 6120 plugged into a Magnatone amp that I’d modified so that it ran at 100 watts. Boy, that was loud, but so clean and clear.”

Eddy was quick to give credit where it was due and acknowledged that Hazlewood’s production made a huge difference to the sound of the record. “[Hazlewood] really went to town with the echo,” Eddy said. “We’d already recorded the track with quite a lot of echo in Phoenix, but then he took it to Gold Star Studios in [Los Angeles] and added even more.”

Once the hits started to roll in, Eddy would tour up and down the States on Dick Clark’s rock ’n’ roll package tours. What most people might not know is that whenever the bus driver got tired, Eddy would take over.

“I always wondered how Dick Clark reacted when he found out, because there really was a million dollars’ worth of talent on the bus – and if I’d crashed it, the insurance claims would have been enormous!”

While Scotty Moore (with Elvis Presley), Cliff Gallup (with Gene Vincent), and James Burton (with Ricky Nelson) were pioneers of the burgeoning art of rock lead guitar, they were essentially sidemen. Eddy, meanwhile, was upfront and in your face, without vocals to dilute the impact.

The lines he played might have seemed simple at times, but when he needed to, Eddy could blaze; witness the driving intro of Movin’ or his killer blues licks on Three-30 Blues.

Eddy’s fifth hit, Peter Gunn (1959), was written by Henry Mancini for the TV show of the same name and was clearly inspired by Eddy’s sound. Eddy remembered meeting Mancini after he’d taken his version into the charts.

“I was at the movie studios where he was working, and he called out to me to hold up a minute. He ran up to me and thanked me for making him so much money from Peter Gunn.”

Ironically, although Eddy made plenty of money for other people, his modest personality led others to take advantage of and exploit him.

“I never got the royalties I deserved from Jamie, my record company,” he said. “Tour promoters ripped me off; I used to think we should be doing a lot better than we were, given our success, until I realized people were badly mismanaging me.

“Later, I signed to RCA, who got into a muddle with some of the money they owed me. When they paid it back, my representatives took the money as a single payment rather than spreading it out over the length of my contract, so it was taxed as a single year’s earnings.”

Eddy’s success wasn’t confined to the States; he scored hits around the world, particularly in the U.K., where he was an influence on the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and Jeff Beck.

Rock ’n’ roll maintained its popularity outside America long after the thrill had faded in the States; any act that toured the U.K. in the Fifties was greeted with the kind of hysterical scenes that would later become the norm for the Beatles, and the following for the music in England was so strong that a rock ’n’ roll festival in 1972 featuring Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Bo Diddley filled Wembley Stadium, one of the largest outdoor sports arenas in the country.

The Duane Eddy Circle, one of the longest-running fan clubs for any artist, is based in the U.K. Founder Arthur Moir became good friends with Eddy over the decades and remembers that Eddy had a particular affection for his legions of fans around the world.

Moir notes that Eddy was very modest about his status and place in the lineage of guitar greats. “He was very grateful for the numerous awards he won, and I think the respect he received from other artists was equally important to him,” Moir said. That respect was demonstrated by the amount of guest appearances Eddy made with numerous legendary figures over the length of his career, ranging from Foreigner to Hans Zimmer.

According to Moir, Eddy didn’t look back on his career with anything other than modesty.

“I’m sure he was aware of his status and his place in history, but there was no sign of ego,” Moir said. “He was the star, but he also felt that he was one of the band. He gave credit to the Rebels (his band) by including their names on album sleeves – not just the studio musicians but also the touring Rebels. That was unheard of at that time.”

The hits started to dwindle in the Sixties. (Dance with the) Guitar Man (1962) was his last significant chart entry, and Eddy spent a few years working as an actor, mainly appearing in Westerns. But he continued to record, releasing some of his most artistically satisfying albums, including Songs of Our Heritage (1960) and Duane Does Bob Dylan (1965).

Dylan was a fan of the album and even cited it in his 2004 autobiography, Chronicles: Volume One, where he wrote, “My lyrics had struck nerves that had never been struck before, but if my songs were just about the words, then what was Duane Eddy, the great rock-and-roll guitarist, doing recording an album full of instrumental melodies of my songs?”

It seemed that the prospect of further chart success was a distant dream by 1975, yet – remarkably – Eddy scored a worldwide Top 10 with Play Me Like You Play Your Guitar, which was followed, even more surprisingly, in 1986 by a reworking of Peter Gunn by U.K. collective Art of Noise.

In 1987, he released one of his greatest achievements, the annoyingly hard-to-find Duane Eddy: His Twangy Guitar and the Rebels, which features guest appearances and/or production by George Harrison, Paul McCartney, Jeff Lynne, John Fogerty, and Ry Cooder, not to mention The Trembler, a one-of-a-kind Duane Eddy/Ravi Shankar co-write.

According to Moir, there are several unreleased treasures in the vaults that really should be available by now.

“The most important is Artifacts of Twang,” he says. “One track includes a collaboration with Brian Setzer; another was the last ever track that Phil Everly recorded. There’s also an album he recorded for Colpix, but the label folded before it was released. He recorded Tokyo Hits for Reprise, to be issued only in Japan; it really needs a worldwide release.”

Eddy never tired of touring, frequently playing dates around the world, even in his eighties, and never tired of playing the old hits that he must have performed thousands of times, just as he never lost his enthusiasm for the guitar.

“There’s something that’s special about a guitar in its case,” he said. “You know there is all that magic just waiting to come out when you open it up, and every time you get the guitar out, it never lets you down.”