I found Barbie again during 2020’s COVID lockdown. Indoors, confined to Juicy Couture tracksuits, I was missing excuses to express my hyper-femininity through clothing, as I had done pre-pandemic. Collecting Barbie dolls became a way to display my love of femininity in all it’s fun, ridiculous and pink-saturated possibilities.

My shelf of Barbies – from Western Winking Barbie (1981) to Enchanted Evening Barbie (1995) – is now my favourite part of my home. But for many, her rediscovery will come through Greta Gerwig’s upcoming movie, Barbie – the doll’s first live action film, starring Margot Robbie.

As an artist and a researcher of expressions of femininity, Barbie is a constant source of inspiration to me. The doll is a conduit for cultural ideas surrounding femininity and the endless ways it can be played with.

“Hyper-femininity” describes femininity at its most extreme, at the far end of the spectrum of different gender expressions. Contemporary expressions of hyper-femininity are often intended to subvert aspects of hegemonic femininity (expressions of femininity that reinforce traditional gender roles). These versions of hyper-femininity reclaim aspects of patriarchal, traditional femininity and play with, perform and parody it.

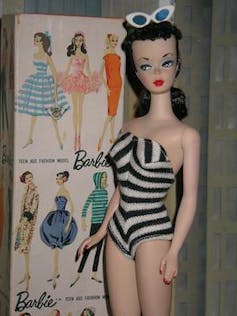

First created by Mattel co-founder Ruth Handler in 1959, Barbie is a pop culture icon. For children, Barbie has been a beloved friend. For artists including Andy Warhol, a muse. And – depending on who you ask – either an ally or enemy of the feminist cause.

It’s Barbie’s hyper-femininity – with her shiny blonde hair, perfect make-up and excessively pink wardobe – that often causes these vast differences in opinion.

Barbie’s complicated feminism

In her book, Forever Barbie: The Unauthorised Biography of a Real Doll, author M.G. Lord describes Barbie as a complicated and contradictory pop-culture figure. Lord sees Barbie as a “reflection of American popular cultural values and notions about femininity”. Over its 64-year history, the doll’s evolution has reflected the often contradictory demands and ideals placed on women.

Some feminists argue that Barbie’s hyper-femininity isn’t self aware in the way that, for example, the hyper-femininity of drag queens is. Instead, they say, Barbie reflects a more hegemonic femininity, with her idealised and impossible feminine body criticised as perpetuating harmful female beauty standards.

Even Barbie’s “curvier” builds have been called out for failing to measure up to the “average” woman’s body. When scaled up, “curvy” Barbie would in fact be a UK size eight.

And the problems don’t end with Barbie’s body. In 1992, the talking Teen Talk Barbie was criticised for using phrases such as “Math class is tough”, echoing gender stereotypes.

However, Barbie is also capable of subverting hegemonic femininity. Barbie has been marketed as an unmarried career girl since her inception, during an era where women were severely underrepresented in the workforce.

With her first few careers including fashion designer (1960), nurse (1961) and astronaut (1965), Barbie stood as a role model to girls who showed there were options for their future beyond homemaking.

Now, Barbie has had over 200 official careers. Often decked out in her signature pink, the doll has showed generations that they do not have to sacrifice their love of femininity in order to succeed. She has also changed her appearance over time, with Barbie appearing as different races and body types. In April, Mattel released a Barbie doll with Down’s syndrome.

Rebranding Barbie

In 1997, Mattel launched a lawsuit against Danish-Norwegian pop group, Aqua. The company alleged that the band’s song Barbie Girl, released the same year, infringed upon Mattel’s trademark and imposed an adult image onto Barbie.

The song featured lyrics such as “I’m a blonde bimbo girl in a fantasy world”. “Bimbo” is a derogatory word for hyper-feminine women who are perceived as being unintelligent. In 2002, a California federal appeals court dropped Mattel’s lawsuit.

Fast forward 20 years and the soundtrack to the Barbie movie features a song by rappers Ice Spice and Nicki Minaj entitled Barbie World, which samples Aqua’s Barbie Girl. With lyrics such as “I’m a Barbie girl, pink Barbie Dreamhouse/The way Ken be killin’ shit got me yellin’ out like the Scream House”, the pair position Barbie-branded hyper-femininity as a source of sexual empowerment.

The inclusion of the Aqua sample in the Mattel-approved film marks a shift – the brand is now leaning into the song. Perhaps this further indicates a transition from resisting Barbie’s bimbo reputation to embracing it.

This reflects a wider vindication of the bimbo figure in recent years. Posts to social media platform TikTok reclaiming the term are proving wildly popular, with one self-professed bimbo influencer boasting 4.6 million followers.

Read more: Greta Gerwig’s Barbie movie is a 'feminist bimbo' classic – and no, that's not an oxymoron

Hyper-feminine identities have been belittled within some feminist writing (such as Ariel Levy’s Female Chauvinist Pigs in 2005), because they’ve been interpreted as a submission to the male gaze and patriarchal oppression. But this recent bimbo renaissance has highlighted how embracing hyper-femininity can, for some, be subversive, joyful and empowering.

In the trailers for the upcoming Barbie movie, Barbie Land is a matriarchal society where hyper-femininity is a sign of power. In one trailed scene, Barbie (Margot Robbie) explains: “Basically everything that men do in your world, women do in ours.”

Now in her movie star era, Barbie is unashamedly embracing her hyper-feminine gender expression and its subversive and playful possibilities. To echo Barbie’s 1985 advertising slogan: “We dolls can do anything.”

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Launches August 4. Sign up here.

Daisy McManaman does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.