Policies and decisions made in the United States echo around the world and often have widespread implications. Take sexual and reproductive health, for example. Decisions made in the US have caused, and could cause, severe damage to progress in access to these services in developing countries.

The first US policy with implications for healthcare in other countries is the global gag rule, first enacted by Ronald Reagan in 1984. Under this policy, non-US organisations that receive US government funding cannot provide, refer for, or promote abortion as a method of family planning. Successive US presidents have decided whether to enact or revoke the policy. President Joe Biden set it aside when he took office in 2021.

Read more: US anti-abortion "gag rule" hits women hard: what we found in Kenya and Madagascar

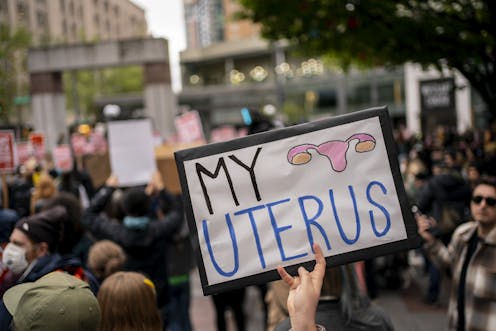

The second is the decision before the US Supreme Court on the right of women to choose abortion. Recently leaked documents suggest the court may overturn the landmark 1973 decision, Roe v Wade, that gave American women this choice. The final decision is expected in a couple of months.

For countries that look to the US for guidance and for funding, the consequences will go beyond abortion. The striking down of Roe v Wade, coupled with the global gag rule (if and when it is reinstated by a Republican administration), empowers national and international opposition to sexual and reproductive health services such as family planning, abortion, and comprehensive sexuality education.

In African countries, where incremental gains are beginning to manifest in improved legislation and policies due to decades of advocacy and lobbying, this would be a devastating blow. For example, in 2020 we studied the impact of the global gag rule in Kenya. Our findings pointed to government officials using the US government position to restrict conversations around abortion in official meetings.

What happens in the US may effectively deny women their rights and set back the sustainable development agenda target of reducing maternal, neonatal, and child morbidity and mortality.

Global gag rule

In 2017, under President Donald Trump’s administration, the US government reinstated and expanded the global gag rule. Republican administrations have typically reenacted the policy focusing on family planning assistance. But the Trump global gag rule expanded the scope to cover most categories of US government global health assistance instead of only family planning assistance.

Biden’s administration has rescinded the policy. But the reverberations of its application between 2017 and 2021 are still being felt across the globe.

The US is one of the largest public health donors. Many African countries depend on external assistance for funding aspects of healthcare, including family planning and quality post-abortion care.

Read more: Insights into how the US abortion gag rule affects health services in Kenya

Roe v Wade

Roe v Wade stipulated that the US constitution protected a pregnant woman’s right and freedom to choose to have an abortion without excessive government restriction.

The leaked draft majority decision of the US Supreme Court to overturn this will set back gains made in sexual and reproductive rights and freedoms and improvements in maternal, neonatal, and child health indicators across the globe.

Increasingly, countries in Africa are moving towards liberalisation of abortion laws and, to some extent, decriminalisation of abortion. For example, the Democratic Republic of Congo is improving access to safe abortion. Many consider this as progress.

Even before the issue came before the Supreme Court, several US states had made laws that limit access to safe and legal abortion, allowing abortion for only up to six weeks of gestation. The US has strong institutions and systems to contest and possibly overcome such decisions. It could even codify legal abortion in the constitution.

But women in countries that look to the US for guidance and for funding may not have those options.

The right to choose

Evidence is clear that restricting abortion does not reduce the incidence of abortion. Instead, it makes abortion less safe. Women and girls who are denied access to safe procedures are forced to use unsafe methods and providers. Unsafe abortion can cause complications that range from moderate to life-threatening. More than 77% of abortions in Africa annually are unsafe.

Poorer and marginalised women and girls bear the heaviest burden when their right to choose is denied. Rich and powerful people can find a way to meet their needs. But poor people are forced to have more children than they can afford. The lack of family planning methods and safe and legal abortion is a danger to women’s health. It also puts women and girls at risk of greater poverty.

US influence in African countries

US policies, particularly the impending Roe v Wade Supreme Court decision, will permeate the international community. African governments that subscribe to conservative sexual and reproductive health norms may draw inspiration from such decisions.

The US ruling could lend support to African decision-makers who are against providing women with options. They might use it to deny women access to critical healthcare in contradiction of their rights.

Anti-choice civil society movements, too, will draw impetus and validation from such a ruling to oppose progressive actions and policies at the national and sub-regional levels.

Several sub-regional economic blocs in Africa are in the process of enacting sexual and reproductive health laws. For example, a sexual and reproductive health bill is currently at the East African Legislative Assembly. Reversal of Roe v Wade might stall or terminate such processes.

Boniface Ushie works for the APHRC, which receives funding from Sida.

Kenneth Juma works at the African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC), which receives funding from Sida.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.