The James Webb Space Telescope is able to peer closely at exoplanets one at a time and examine their atmospheres with unprecedented accuracy. But perhaps the most exciting planetary targets will be a star system strangely analogous to our own: the TRAPPIST-1 system.

The James Webb Space Telescope is able to study exoplanets, giving us a clearer (still fuzzy) picture of what planets beyond our own Solar System look like and critical details about their composition — including whether they might be able to support life. In its first year, Webb will look at some 70 exoplanets, but NASA exoplanet expert Knicole Colòn explains that TRAPPIST-1 is particularly notable for several key reasons.

“The TRAPPIST-1 system is the top of everyone’s list,” she says.

What is TRAPPIST-1?

TRAPPIST-1 is a star first discovered in 1999 and then dubbed 2MASS J23062928-0502285. It is an ultracool red dwarf star, which means it is among the coolest of dwarf stars — and it is a mere 4,400 degrees Fahrenheit, or 2,430 degrees Celsius (the Sun is almost 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit at its surface, for comparison’s sake). TRAPPIST-1 is just nine percent as massive as the Sun.

TRAPPIST-1 is some 40 light-years from Earth — beyond the reach of any human-made craft conceivable now, but on the scale of the galaxy, TRAPPIST-1 is the kooky but nice neighbor who lives one street over and invites you to barbeques each summer.

TRAPPIST-1 got its current name after scientists discovered three exoplanets orbiting the star in May of 2016 using the transiting method, whereby dips in the star’s light betrayed the planets’ existence to astronomers. The find came from observations made by the Transiting Planets and Planetesimals Small Telescope (TRAPPIST, get it!) which is a ground-based observatory in Chile.

And lo, 2MASS J23062928-0502285 became TRAPPIST-1, and its planets were called TRAPPIST-1b, TRAPPIST-1c, and TRAPPIST-1d.

The TRAPPIST-1 system, explained

Just a couple of months after their discovery was announced in July 2016, Hubble data revealed TRAPPIST-1b and TRAPPIST-1c both didn’t appear to have thick gas atmospheres — hinting they may be rocky planets, like Earth. Both TRAPPIST-1b and TRAPPIST-1c are also small planets — about the same size as Earth.

“The lack of a smothering hydrogen-helium envelope increases the chances for habitability on these planets,” says Nikole Lewis, then of the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, according to a statement to NASA at the time.

“If they had a significant hydrogen-helium envelope, there is no chance that either one of them could potentially support life because the dense atmosphere would act like a greenhouse,” she explains.

Since then, scientists have discovered four more planets orbiting TRAPPIST-1. This is interesting because our own Solar System has eight planets orbiting a single star, so it’s a similar number of planets, but the two systems look very different from one another.

“This is a really small star that has seven planets that are all [similar to the] size of Earth,” Colòn explains. “A few of those planets are in the Goldilocks Zone.”

The Goldilocks Zone, for clarification, is the name given to the area near enough and far enough from a star where a planet could feasibly sustain liquid water at the surface — a key ingredient for habitability.

NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope and ground-based telescopes later helped to confirm two of the planets found in 2016 and discovered all the other planets in orbit using the transit method. The Spitzer mission ended in January 2020, but back when it was doing science it observed the system for more than 1,000 hours. Kepler, also now in retirement, studied the system, too. Now, it will be up to the James Webb Space Telescope to continue this work.

“Every single one of those seven planets will be observed by Webb in some way,” Colòn confirms.

TRAPPIST-1 vs. the Solar System

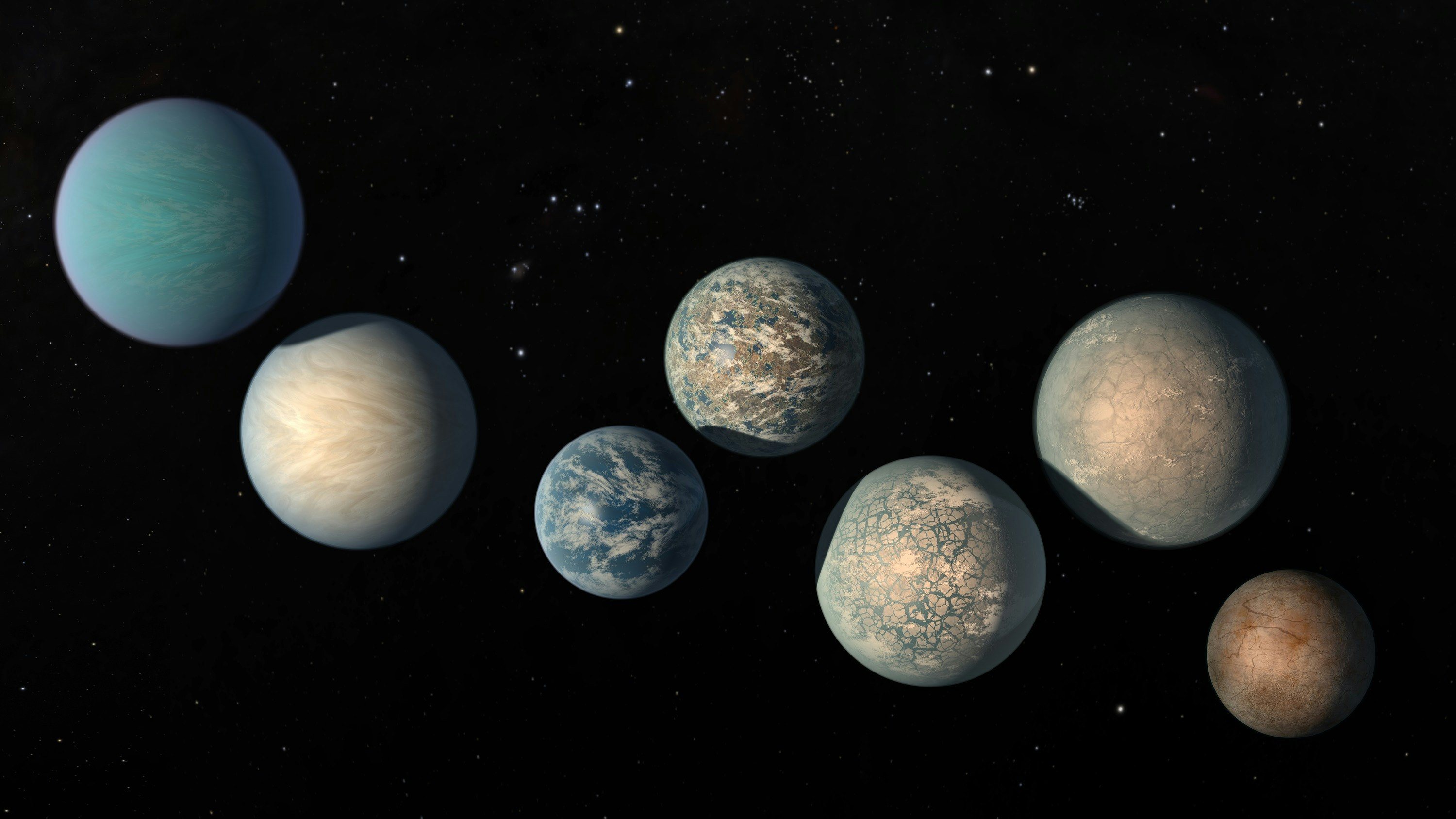

TRAPPIST-1 has seven planets in orbit, almost as many as our own star. But the TRAPPIST planets are rather different from the orbs we know best.

All of the TRAPPIST planets orbit very near to their star — in fact, they are so close to their star that their orbits all would fit inside the orbit of Mercury, which is the nearest planet to the Sun. TRAPPIST-1b orbits the star in a mere 1.5 days, but it is a similar size and mass to Earth.

This is where things get interesting: All the TRAPPIST planets are all a similar size to one another and all of them appear to be rocky planets. Indeed, the TRAPPIST planets all look suspiciously Earth-like.

“Some of them are not habitable at all — they're too hot or too cold,” Colòn says. “Webb is still going to be able to provide us with a big comparative project where we can say: Do these planets have anything similar or in common? Because they’re so similar in size and they formed around the same star.”

By combining direct observations with computer models, scientists believe the TRAPPIST planets have a density commensurate with them being rocky planets, but it is hard to tease out their features from such measurements, like whether they are more like the Moon — barren and gray — rather than Earth — wet and green.

"Densities, while important clues to the planets’ compositions, do not say anything about habitability,” said Brice-Olivier Demory in a statement to NASA in 2018. Demory is a co-author of a study detailing the planets’ features and a professor at the University of Bern. For example, though the planets are not puffy gas giants, they may yet prove to have conditions more similar to Mars or Venus than to Earth.

Some of the TRAPPIST planets appear to hold significant amounts of water, too, although it is unknown if this water might exist as a liquid on any of the planets’ surfaces in the same way it does here on Earth. Some of the TRAPPIST planets may be more like ocean worlds, while the ones further out from their stars may be much more arid or icy.

How Webb will study TRAPPIST-1

These differences and commonalities with our own planet and Solar System are, however, what makes the TRAPPIST system so intriguing for Webb to study, Colòn says.

“It’s one of the first real opportunities we have to study literally seven planets around the same star,” Colòn says. At stake is answering a question that is both scientific and philosophical: Why are we here?

“Every single planet, even Jupiter-sized ones, really help our understanding of how our own Solar System formed,” Colòn says.

“There’s a lot of other planets that exist out there that are and just so many are different from our own. That raises a question: How did our Solar System form exactly as needed? And is our Solar System architecture something that is needed for life to form?”

“If Earth is the only livable planet that we know of,” she continues, “then we need to know that because if this is the only planet, then we need to save our planet, right?”