When a powerful storm flooded neighborhoods in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, in April with what preliminary reports show was 25 inches of rain in 24 hours, few people were prepared. Even hurricanes rarely drop that much rain in one area that fast. Residents could do little to stop the floodwater as it spread over their yards and into their homes.

Studies show that as global temperatures rise, more people will be at risk from such destructive flooding – including in areas far from the coasts that rarely faced extreme flooding in the past.

In many of these communities, the people at greatest risk of harm from flash flooding are low-wage workers, older adults and other vulnerable residents who live in low-lying areas and who have few resources to protect their properties and themselves.

I study the impact of extreme weather on vulnerable communities as an assistant professor of social work. To limit the damage, communities need to know who is at risk and how they can be better prepared.

More extreme downpours in a warming world

The Fort Lauderdale storm on April 12-13, 2023, offered a view into the risks ahead as temperatures rise.

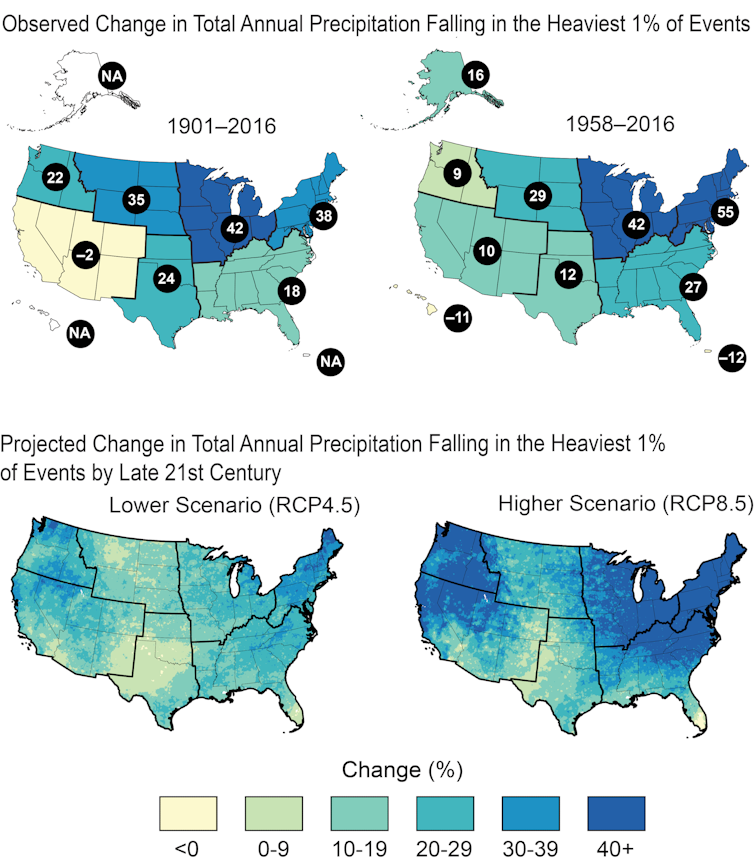

A warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture, leading to stronger downpours. The resulting deluges can be devastating. These events are expected to increase in frequency and intensity in many regions as greenhouse gas emissions from human activities continue to heat up the planet.

Recent disasters, including several in 2022 and in 2023 already, show how the risk of flash flooding is expanding beyond areas traditionally considered at risk.

Knowing who is most at risk

To plan for extreme weather, it’s crucial for community leaders and residents to know where the risks are highest and who might not be prepared.

Low-lying areas with poorly planned development, lack of investment in protective infrastructure and the lingering effects of historic disinvestment and discrimination are often at higher risk. So are low-income communities with tight budgets that can’t afford protective measures like upgraded levees or stormwater systems and can’t recover from damage quickly.

When older adults live in these flood-prone areas, they are at even higher risk. Older adults have a higher likelihood of having health needs or some form of disability that could affect their ability to leave quickly during a disaster. They are also more likely to be socially isolated, which may mean they don’t hear timely information or have help to evacuate or quick access to resources for recovering.

Renters and the impact of housing insecurity

In a recent study, my colleagues and I looked at how prepared people were for disasters of any kind across the U.S. – flooding, tornadoes, hurricanes and others – and how housing security played a role. The numbers were sobering.

Overall, we found 57% of the population, among 29,070 housing units surveyed nationwide, reported they were not prepared with food, water, emergency funds and transportation in case disaster struck. We found that households facing housing insecurity – those behind on their payments for rent, mortgage or utilities – were less prepared for disasters than others, even when the occupants had similar incomes and educations.

People who are struggling to meet day-to-day needs often don’t have the ability and resources to plan for everyday events, let alone for disasters. Our research has shown that households with children, households led by women, and low-income households were less prepared than others for disasters.

Renting adds additional challenges. In the U.S., lower-income families often depend on the rental market. They tend to move more frequently, and since they don’t own the property, they often can’t make upgrades for safety. And landlords might not prioritize those risks that seem rare but carry costs.

How to help communities stay safe

The most effective way to address these challenges is through solutions that are tailored to the community.

That can involve investing in infrastructure, including state-funded priorities like drainage systems and large-scale flood prevention measures, as well as ensuring that people have access to safe and affordable housing. Some communities and federal agencies have bought out properties that frequently flood and changed zoning rules to prevent more people from moving into harm’s way.

Raising community awareness about climate change and extreme weather risks is also crucial, especially among those most at risk, such as older adults. If people understand the risks, know how to prepare their homes, know how to plan for emergencies and know where to find assistance, they’re more likely to be prepared when disasters strikes.

I believe the most successful efforts are those that bring at-risk communities into planning discussions.

For example, in Columbus, Ohio, the city is working with the Central Ohio Area Agency on Aging, Age Friendly Innovation Center and my team to improve disaster preparedness among older residents. We hope to learn from older adults in affordable housing communities who have experienced extreme weather in recent years to help design action plans for communities with special needs. The goal is to ensure residents are better prepared for climate- and weather-related emergencies in the future.

Smitha Rao does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.