Bronzeville probably would look very different today if it weren’t for the passion of Harold Lucas.

Mr. Lucas, the son of a Pullman porter and grandson of a renowned chef who brought tastes of the world to the family table, knew all about Bronzeville’s glory days and never stopped educating people about them. Other activists and community leaders say his outspoken advocacy contributed to the preservation of some of the most historic buildings in the South Side neighborhood once known as the Black Metropolis.

“My heart,” he once said, “has a vision of Bronzeville restored.”

The longtime Bronzeville resident, who had faced cancer and a stroke, died Aug. 9 at the Estates of Hyde Park. He was 79.

“He died a few days before I was planning to bring him out of the nursing home,” his sister Lydia Lucas said.

“He was a giant,” said Shannon Bennett, executive director of the Kenwood Oakland Community Organization, who called him the “foremost proponent” of efforts to see Bronzeville recognized as “the Black Harlem of Chicago” and ensure that its brick-and-mortar past survived.

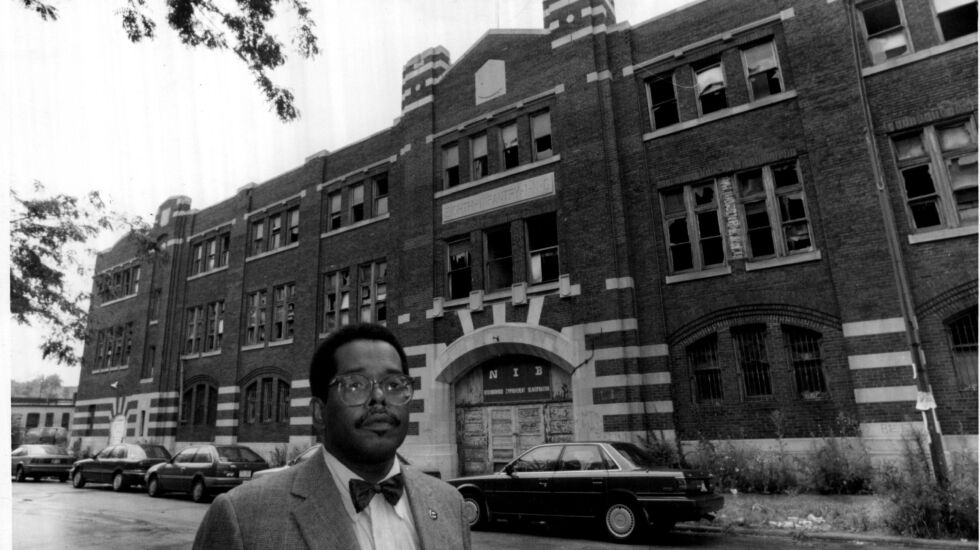

Bennett said Mr. Lucas’ legacy includes helping get city landmark status for the Overton Hygienic Building at 36th and State streets — once a hub of Black commerce — and for the former Eighth Regiment Armory building at 35th Street and Giles Avenue. The nation’s first armory built for a Black regiment, it’s now home to the Chicago Military Academy.

Mr. Lucas also helped gain city landmark recognition for the building that housed Supreme Life, 3501 S. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Dr., the first Black insurance company in the northern states.

“As you walk and drive around Bronzeville, Harold’s works are everywhere,” said Nathan Thompson, author of “Kings: The True Story of Chicago’s Policy Kings and Numbers Racketeers.”

“None of the work would have been possible without him being the drum major,” said Ald. Pat Dowell (3rd).

Mr. Lucas also fought against demolition of the South Shore Country Club.

In his later years, he led bus tours of Bronzeville. He’d tell people how, in the days of the Great Migration, Bronzeville pulsed with Black industry, ambition and creativity. Racism and restrictive real estate covenants circumscribed home ownership in most of Chicago. But in Bronzeville, Black people headed businesses and produced sublime music and works of literature.

“Harold made the history come alive for us,” Bennett said. “He made you think you were in one of the speakeasies or hearing the great jazz musicians from the Savoy Ballroom or Gerri’s Palm Tavern.”

The term “Bronzeville” was coined in 1930 by an editor of the Chicago Bee, a Black newspaper, according to the 1945 book “Black Metropolis.” But Mr. Lucas helped repopularize it “to brand the current community,” Dowell said.

Mr. Lucas — who was chief executive officer of the Black Metropolis Convention and Tourism Council — pushed for historic recognition but also tried to make sure neighborhood residents didn’t lose out.

“The first time I heard ‘gentrification,’ it came out of the mouth of Harold Lucas,” Thompson said. “Harold was never afraid to get in your face and talk about these things.”

“There is a whole generation of community activists and community organizers who have helped us make tremendous strides in opening up housing opportunities for people and people of color,” the Rev. Jesse Jackson said. “Harold was one of the freedom fighters.”

He was one of five children of Katherine and Harold Lucas. His father and his great-grandfather Cyrus Stewart were Pullman porters, according to his sister, and their mother worked at a Neumode hosiery store, selling women’s stockings.

His paternal grandmother Ida Lucas was a daughter of Charlotte Downs, an enslaved child until emancipation. Ida Lucas became a chef at the Edgewater Beach Hotel.

“She exposed us to foods we would never have had living on the South Side of Chicago” and taught her children how to do formal place settings, according to Lydia Lucas.

Young Harold went to Ray and Wadsworth grade schools and Hyde Park High School, then the old Loop Junior College and Malcolm X College.

At one point, he was a partner in the 632 Fusion nightclub at 632 N. Dearborn St., now Tao Chicago.

“People like Chaka Khan, jazz artists, anybody who was popular in the ’70s passed through their door,” his sister said.

Mr. Lucas also owned a “head shop” for a time on 71st Street, the Equinox, she said.

“Daddy loved jazz,” said his daughter Sherri Lucas-Hall, especially John Coltrane and Miles Davis.

In addition to his daughter and sister Lydia, Mr. Lucas is survived by his son Eli Lucas, sisters Helen Lucas and Harriet Herron, three grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

Thompson said a “Bronzeville tribute” is planned for Mr. Lucas on Sept. 28, possibly at a building he helped save — The Forum, at 43rd Street and Calumet Avenue.