For one whole year, Han Kang found herself unable to write – a disturbing development for a prize-winning author with a novel on the go. “I couldn’t write or read fiction,” she says. “I couldn’t even watch things.” When the South Korean author tried, words evaded her; she turned to documentaries, books about science. In truth, Han’s clean, masterful prose and subsequent critical acclaim have always belied a life-long struggle with language. “It is an impossible medium. It’s always failing,” she sighs. “Starting out as a poet, I’ve always felt that – but particularly that year, I felt it more. This impossibility of language.”

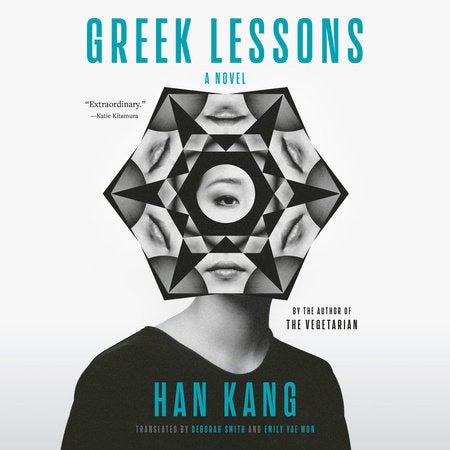

The words returned, but the experience left a mark – traces of which are all over her elliptical, resonant novel Greek Lessons. Its protagonist, having suddenly, mysteriously lost her ability to speak, finds solace in the classroom with her ancient Greek teacher who is, in turn, losing his sight. Written in 2011, the book is only now being published in English, following the success of Han’s other translated works. Greek Lessons, though, operates on a quieter register than her previous books. Its pages contain nothing resembling the graphic self-harm and force-feeding of Han’s fable-like novel The Vegetarian, for which she received global recognition and the Man Booker International Prize in 2016. Nor do they share the bloody ferocity of Human Acts (2014), a story that unfurls in the long shadow of a historical massacre.

Even now as Han, 52, describes that troublesome period during which she lost her “only medium”, her voice is soft but her metaphors are sharp, visceral, capable of drawing blood. “Language was like a double-bladed sword that I really wanted to grasp, but it wasn’t possible,” she says, setting her teacup down and placing her palms around an invisible knife. There was no particular reason, she clarifies – unlike the protagonist of Greek Lessons, whose therapist suggests, futilely, that her sudden muteness is a result of her mother dying and losing custody of her son. “I didn’t take Greek lessons either,” says Han, who is an easy conversationalist and generous with a smile. Only half the time does Han actually make use of the translator with us. And when she does, she takes care to listen and ensure her words are being faithfully conveyed.

Violence – “its omnipresence” – has concerned Han since she was young. The daughter of novelist Han Seung-won, she was born in Gwangju, a provincial city near the tip of the Korean Peninsula. Her family moved to Seoul when she was nine – four months, coincidentally, before her birthplace was devastated by the Gwangju uprising. Peaceful protestors and bystanders were brutally killed. When she was 12, Han discovered a book about the massacre hidden at home. In it were photographs of mutilated faces and bayoneted bodies. “I felt the fear and shock deeply inside me. It made me think how far humanity can go and still be human,” she says. “That has always stayed with me and it’s something I have to constantly recreate. It’s a conundrum, a fundamental question within me, so it comes out in whatever I write.”

In Greek Lessons, the violence is muted but present. Interestingly, it’s not the loss of language that Han depicts in these terms, but language itself. As a child, the protagonist experiences words that “thrust their way into her sleep like skewers” and “confine her like clothing made from a thousand needles”. Her point is: language is not always helpful. “You’re sometimes in a place where you’re in so much pain that you want to encapsulate yourself away from the world we’re living in,” Han explains. “You want to go into a corner of darkness all alone in total silence. In that moment, language becomes completely useless.” Even that period of no writing, albeit troubling, was helpful. “It gave me an opportunity to look inwards and observe myself.”

Greek Lessons inevitably brings up questions about translation. It’s an apt conversation for Han; not only have her works been translated, but the translations themselves have provoked controversy in the past. In 2016, The Vegetarian – about a woman who refuses to eat meat before rejecting food in any form – became the first Korean-language novel to win the Man Booker International Prize. It was awarded both to Han and translator Deborah Smith, whose work on the book was praised. Soon, however, in the Korean media and later internationally, charges of mistranslation swirled. Writing in The LA Times, Charse Yun, a teacher of translation in Seoul, declared his admiration for Smith’s translation but called it a “new creation”. It was, he argued, like Raymond Carver being made to sound like Charles Dickens. Han stood by the translation, and still does. Smith went on to translate Human Acts and later The White Book, Han’s Man Booker International-shortlisted meditation on her older sister who died as a baby. Smith worked on Greek Lessons, too, although this time alongside Seoul-based translator Emily Yae Won.

“I find the translation process to be an extremely intriguing human activity,” says Han now. “I form the starting feature of something but in order to get to the finished form, it needs to lose everything I have created and be reborn.” She compares it to flying from Seoul to London. “Everything is completely evaporated before it is reformed again.” She would appear then to agree with Yun’s assessment that Smith’s translation of The Vegetarian is a “new creation” – but has little problem with that.

She does wish, though, that there had been more time to go through Smith’s draft of The Vegetarian “thoroughly”, admitting that she’d read it only “leisurely” because she was preoccupied with Human Acts. “When I’m working on a new book, I put my 100 per cent in so I didn’t have the luxury to do that,” she says. “Obviously, I wanted to make sure everything I had written was still there, which is why – although it was brief – I managed to go through it and pick up a few points.” Han’s writing is rooted in Korea’s history in a way that is not always detectable to foreigners. For instance, the phrase “priest of May” appears in The Vegetarian. “It has two connotations,” says Han. “Firstly, one of beauty. But the other is a historical, more secret meaning in Korean history because of the May 1980 massacre.” Han explained this to Smith. “I wanted to make sure that the meaning was fully embedded.”

The translation process appears to have grown more rigorous over time. When Human Acts came around, Han worked closely with Smith, going through the draft “paragraph by paragraph”. By the time of The White Book, they had become friends and, over email, went through the draft “line by line”.

For Han, writing is something of a pure impulse – one that exists separate to awards and audiences whom, she says, she never thinks of when working, anyway. She felt zero pressure following the Man Booker Prize success. “I have the good fortune of being able to shut myself down when I’m writing, so any stress or pressure that might’ve been on me, I didn’t feel it.” For some authors, writing one book, let alone multiple, is a struggle. For Han, the struggle lies in writing them all before she dies. “I always have something to talk about.” She is often working on two or even three novels at once. “My speed of writing can’t catch the speed of what I have up here.” She taps her head with her index finger. “So that bothers me a lot. That will be a big problem when I die; I won’t be able to finish all these ideas I have.”

Any stress or pressure that might’ve been on me, I didn’t feel it

And yet when Han lost the ability to write all those years ago, it wasn’t the first time. In her thirties, part way through writing The Vegetarian, she suffered from joint problems in her wrists – reasons unknown. It lasted three to four years, during which it was impossible to write. “I almost gave up.” Eventually, she discovered a technique that eased the pain. Han laughs and picks up two teaspoons to demonstrate. Holding them like pens, she begins tapping away at an imaginary keyboard. “Three years wasted before I finally found this skill and could finish the novel!” As for this most recent hiatus, I ask, what allowed her to resume writing then? She pauses and thinks on it for a while. “Before I wrote Greek Lessons, I had some inner conflict about embracing life, and a world where violence is omnipresent,” she says. “Maybe that year, I was moved forward towards a certain light.”

‘Greek Lessons’ is out now and published by Hamish Hamilton

.jpg?w=600)