This story contains spoilers about ‘Thor: Love and Thunder.’

In the new movie Thor: Love and Thunder, based on recent comic books about the superhero, cancer complicates what it means to be Thor.

The superhero Thor first appeared in 1962, quickly joining the super-team The Avengers. Thor was the epitome of the male superhero: morally upstanding and astonishingly physically powerful.

But recent comic book stories have seen different characters — the original, a male Thor Odinson and, lately, a female Mighty Thor, also known as Jane Foster — team up to command the power of Thor.

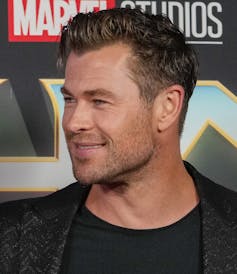

Thor: Love and Thunder, the newly released film by director Taika Waititi, adapts some of these stories. Thor Odinson (Chris Hemsworth) is surprised when, after an eight-year separation, his ex-girlfriend Foster (Natalie Portman) transforms into The Mighty Thor.

Foster as The Mighty Thor has cancer in both the movie and in recent comics.

The character raises questions about the impact cancer has on ideas of worthiness, responsibility and power — and what it means to be a superhero. These are themes we examine in our forthcoming book, The Cancer Plot: Terminal Immortality in Marvel’s Moral Universe.

Bewildered, angry fans

In both the recent comic books and film, Foster controls the enchanted hammer Mjolnir, the weapon that grants superheroic powers to the person who can to lift it.

Some comic book readers reacted negatively to Foster’s time as The Mighty Thor, arguing that Marvel was stripping away or confusing the history of a male Thor superhero in order to introduce gender diversity in its characters.

Read more: Why Ms. Marvel matters so much to Muslim, South Asian fans

Some movie viewers have expressed similar disappointment about seeing a female Thor.

The film’s focus, however, is not on the gender of Thor, but on Odinson’s moral journey. Foster’s spreading cancer is the catalyst for Thor Odinson’s moral growth.

Facing enemies

In both comic books and the Thor film franchise, which began with the 2011 movie Thor, Thor Odinson is a deity: the Norse God of Thunder. A moral exemplar, Odinson could only lift the enchanted hammer Mjolnir if he was worthy.

In both earlier comic books and films, Foster’s typical role was as a minor character. Writers used her as the love interest in danger, giving the male hero someone to rescue.

That is, until she became The Mighty Thor herself.

In Love and Thunder, Foster takes on new enemies: cancer and the cosmic villain Gorr (Christian Bale). While Foster and Odinson vanquish Gorr, they are not able to defeat her cancer.

By taking on Gorr, and risking death from cancer, Foster shows Odinson that a meaningful life is one of emotional and physical risk that may result in loss.

Complicating the superhero

Foster transforms when she holds Mjolnir in both the comic book and movie.

Emaciated from chemotherapy, Foster becomes muscled (and blonde) as The Mighty Thor. The film and comic books link these different bodies through the ethical decisions she must make.

The movie runs up against idealizing narratives of cancer. Cultural critic Barbara Ehrenreich has criticized depictions of cancer as “the source of [one’s] happiness.”

Such narratives minimize the painful process of cancer care to promote a lifestyle brand.

Read more: Cancer and loneliness: How inclusion could save lives

The film mostly avoids this. Cancer becomes the occasion for determining what’s important in life through struggle on behalf of others while facing death.

Foster’s continual decision-making — to have chemotherapy or engage in battle — vividly characterizes the struggle of cancer patients highlighted in critical works and memoirs.

Thus, The Mighty Thor’s cosmic work cannot be separated from her mortal life as a cancer patient.

The cost of superheroism

The same superheroic action has different effects on Odinson and Foster.

For Odinson, the cost of battle does not jeopardize his superhero identity or practice. He can lose a body part, or use a cane when in a temporary human form, but neither puts him at risk of dying.

The costs for Foster, however, are much higher. Foster’s superhuman power, ironically, prevents her cancer treatments from working. Being The Mighty Thor risks killing her.

She must consider death and disease when choosing to battle. Cancer forces The Mighty Thor to make complicated ethical decisions that Odinson doesn’t have to consider.

Renewed life

In both the comic books and the film, cancer kills Foster.

In the years-long comic book story, Foster dies after throwing Mjolnir into the sun.

Odinson rewards Foster with renewed life and the consolation prize of new superhero identity as a Valkyrie, an elite warrior of Asgard.

Love and loss

In Thor: Love and Thunder, Foster’s cancer journey enables Odinson learn a lesson on meaning and risk. While she is in hospital, Odinson begs her to give up Mjolnir so that he won’t lose her.

Despite the likelihood of her death, Foster chooses to live, and die, on her own terms. She joins Odinson in the final battle against Gorr, dying as a result of the wounds she sustains and her cancer.

Early in the movie, fellow superhero Star-Lord (Chris Pratt) talks to Odinson about the loss of own his love. He advises: “I hope one day you can feel this shitty,” a variation on the adage that it is better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all.

How meaning is found

By choosing to make hard moral decisions and take risks, even that of losing him, Foster gives Odinson things to feel shitty about. In this state, Odinson now empathizes with Gorr to the point of taking on the care of his enemy’s orphaned daughter.

Though Foster dies, she is rewarded as The Mighty Thor with entry into Valhalla. However, she enters the place of the gods in her mortal form. Her heroism is not tied to her powers but to her moral decision-making and risk-taking.

Thor: Love and Thunder offers a new way to read Foster’s cancer. It shows how meaning is found in love and risk, not in superpowers.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.