Donald Trump’s new indictment by a grand jury in Washington, D.C., for crimes related to his alleged attempts to overturn the 2020 presidential election, counts as another blow to his reputation.

He might be convicted. But even if he’s not, a set of deeper issues has clearly emerged already: Many leaders and politicians today just cling to power. Heedless of the common good, they seem to forget that the judgment of posterity will come, inescapably.

One clear diagnosis of this problem came almost 40 years ago from Robert Bellah, the renowned American sociologist, when he spotted a momentous transformation. It was 1986, and President Ronald Reagan had entered his second term.

Bellah felt that public officials lived too much in the moment. He feared that politicians had become too ambitious and egotistical, and had come to disregard not only their own reputation, but also, to some extent, the future itself – since “reputation” is a relation among people and among generations.

If politicians think that “private ambition, material aggrandizement, and looking out for number one are the most important things,” Bellah wrote, then they are implicitly suggesting that you should change into “a bad person.”

The transformation lamented by Bellah may not be irreversible, but many public figures have come dangerously close to the tenet once attributed to Louis XV, king of France in the 18th century: “Après moi le déluge,” “After me the flood” – which means that they are largely insensitive to what will remain after they are gone.

And yet, as a historian and author most recently of a biography of George Washington, I’d like readers to know that when America was young, the situation was the exact opposite.

People, especially public figures, were highly concerned about their reputation, or “character,” as it was usually called.

Honeymoon turns to hatred

How a person looked through other people’s eyes was an obsession in the 18th century.

An individual in society, Scottish economist and philosopher Adam Smith wrote in 1759, is “immediately provided with the mirror.” Everyone is “placed in the countenance and behaviour of those he lives with.”

The American founders were particularly concerned about their reputations. Moreover, the judgment of posterity terrified them.

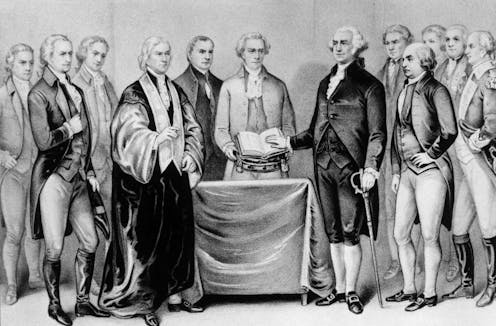

When Washington was about to enter the presidency, he realized his moral stature would suffer. “The eyes of Argus are upon me,” he wrote to his nephew Bushrod Washington in July 1789. Argus Panoptes, the many-eyed giant of Greek mythology, was watching Washington, “and no slip will pass unnoticed.”

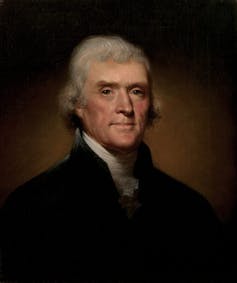

When his turn for the highest office came, Thomas Jefferson also shivered with ominous presentiments.

“I know well that no man will ever bring out of that office the reputation which carries him into it,” he wrote.

Public officials will unavoidably fall from grace, Jefferson concluded: “The honey moon would be as short in that case as in any other, and its moments of ecstasy would be ransomed by years of torment and hatred.”

The founders had good reasons to tremble for their reputation – many of these men enslaved other human beings. At the same time, none of them tried to cling to the role of leader when their time had passed. That was because they dreaded the idea that public opinion would censor them as self-serving and cunning operators.

And, more important, it was because they didn’t want to become an embarrassment, a hindrance, a chunk of gravel in the very machinery of the nation.

Stepping down

Washington, famously, set the example. In June 1799, Jonathan Trumbull Jr., the governor of Connecticut who had also served as Washington’s military secretary during the American Revolution, urged him to run for a third term. Many others had previously prodded him.

But Washington demurred. He was determined not to appear egotistical and be “charged” in the public eye “with concealed ambition.”

Perhaps even stronger, given the country’s heated political climate in the 1790s, there was also Washington’s awareness that he had become a problem himself.

“The line between Parties,” Washington wrote to Trumbull, had become “so clearly drawn” that politicians would “regard neither truth nor decency; attacking every character, without respect to persons – Public or Private – who happen to differ from themselves in Politics.”

Washington was aware that he was no longer the leader in the position to unify the nation in the way he did in the 1780s, at the end of the revolution. Even if he were willing to run for president again, “I am thoroughly convinced I should not draw a single vote” from the opposite side, he wrote Trumbull.

Retiring from public life

The founders were able to create a network of admirers who would serve as stewards of their reputation, while downplaying the missteps they made.

“Take care of me when dead,” old Jefferson begged James Madison, his friend of over 50 years, just a few months before he passed away.

For their part, flawed though these leaders were, they helped their friends and admirers by trying not to make them too uncomfortable. They stayed away from public controversy as much as they could. And when they believed they were done, they retired from the public scene – a political act in its own terms.

Even before entering the presidency, Washington wasn’t at all afraid to “tread the paths of private life.” He would do that eventually, right after his second term, in 1797, and “with heartfelt satisfaction.”

Washington had always accepted the unavoidable fact that, like every other mortal, he also would “move gently down the stream of life, until I sleep with my Fathers.”

Washington would be remembered as the American Cincinnatus. Just like Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus, the mythic Roman statesman and military leader, Washington himself relinquished power – and he did so voluntarily.

Relinquishing power and retiring were the best way to ensure Washington’s glory and reputation.

Apparently, passing the scepter to the next generation and worrying over one’s reputation don’t come as naturally today – at least to some.

Maurizio Valsania does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.