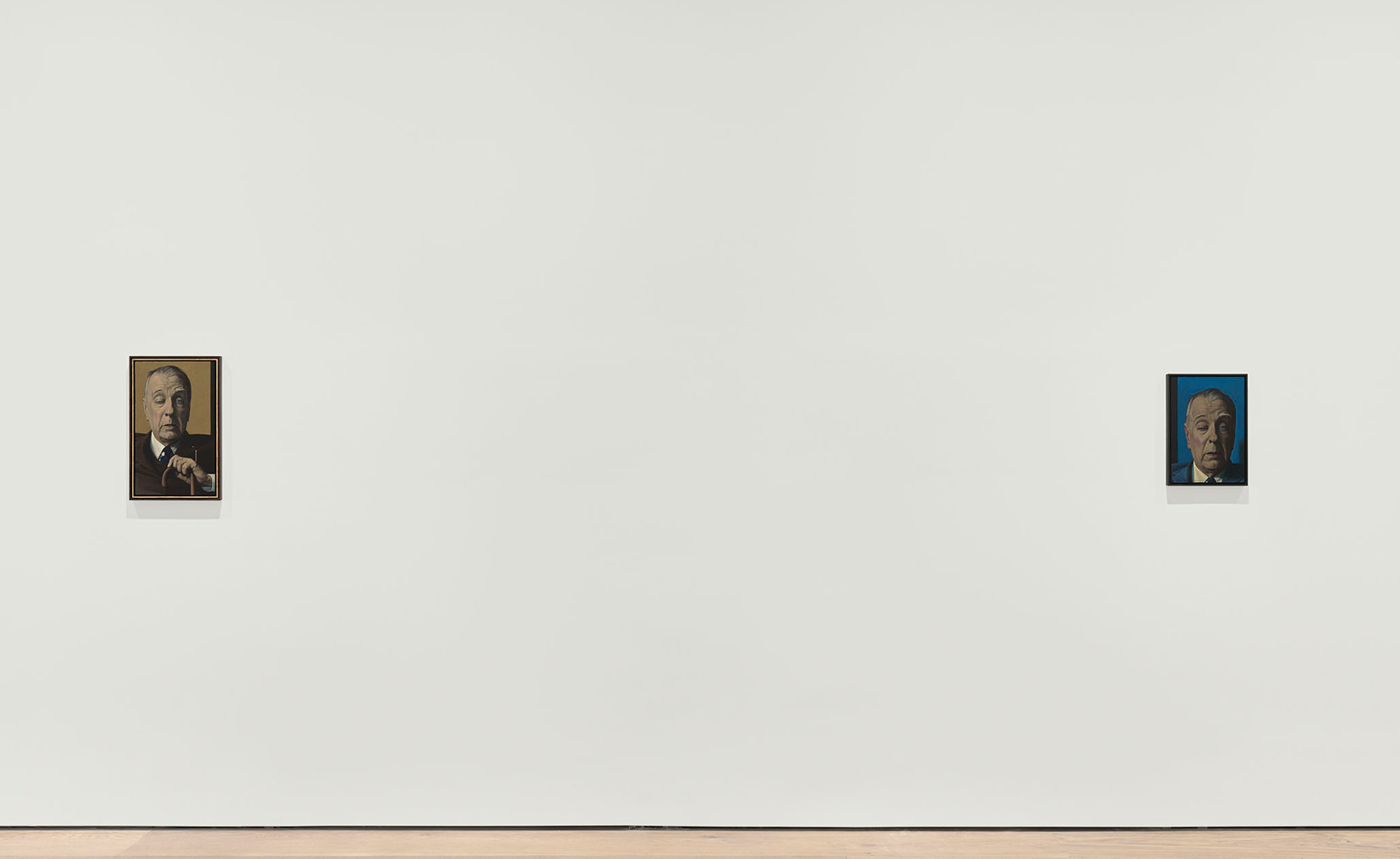

Liu Ye draws on a rich collection of literary references in ‘Naive and Sentimental Painting’, his exhibition currently on show at London’s David Zwirner gallery. The title, which references John Adams’ 1999 symphony Naive and Sentimental Music, offers a clue as to the cultural breadth spanned within.

The exhibition – marking the first time Ye’s work has been seen in London since 2002 – pays tribute to the movements and characters that have shaped his aesthetic. Authors and figures including Vladimir Nabokov, Hans Christian Andersen and William Shakespeare are portrayed here, alongside modern Chinese figures such as actress Ruan Lingyu and writer Eileen Chang. The paintings, rife with historical references and intertwining European and Chinese influences, cast an intimate, atmospheric tone. Here, Liu Ye tells us what inspired him in the creation.

Liu Ye on ‘Naive and Sentimental Painting’

Wallpaper*: You have frequently celebrated contrasts in your work, from Western culture versus Asian culture, to realism versus fairytales. How have you built on your past work and themes in this new exhibition of portraiture?

Liu Ye: My father was a children’s book author, and thanks to his influence, I delved into numerous fairytales during my childhood, with a particular emphasis on the works of Hans Christian Andersen. To this day, I still possess the complete collection of Andersen’s fairytales gifted to my father by Ye Junjian (the Chinese language translator of Andersen’s tales). The translations by Ye Junjian convey an exceptional elegance, and the beautifully melancholic narratives read as if they were originally penned in Chinese. During that time, I was unaware that Andersen was Danish, and I simply believed his surname was ‘An’. When I was a child, I took those fairytale stories to be true, believing that I could actually encounter mermaids, Thumbelina, and such; I mixed up reality and fantasy.

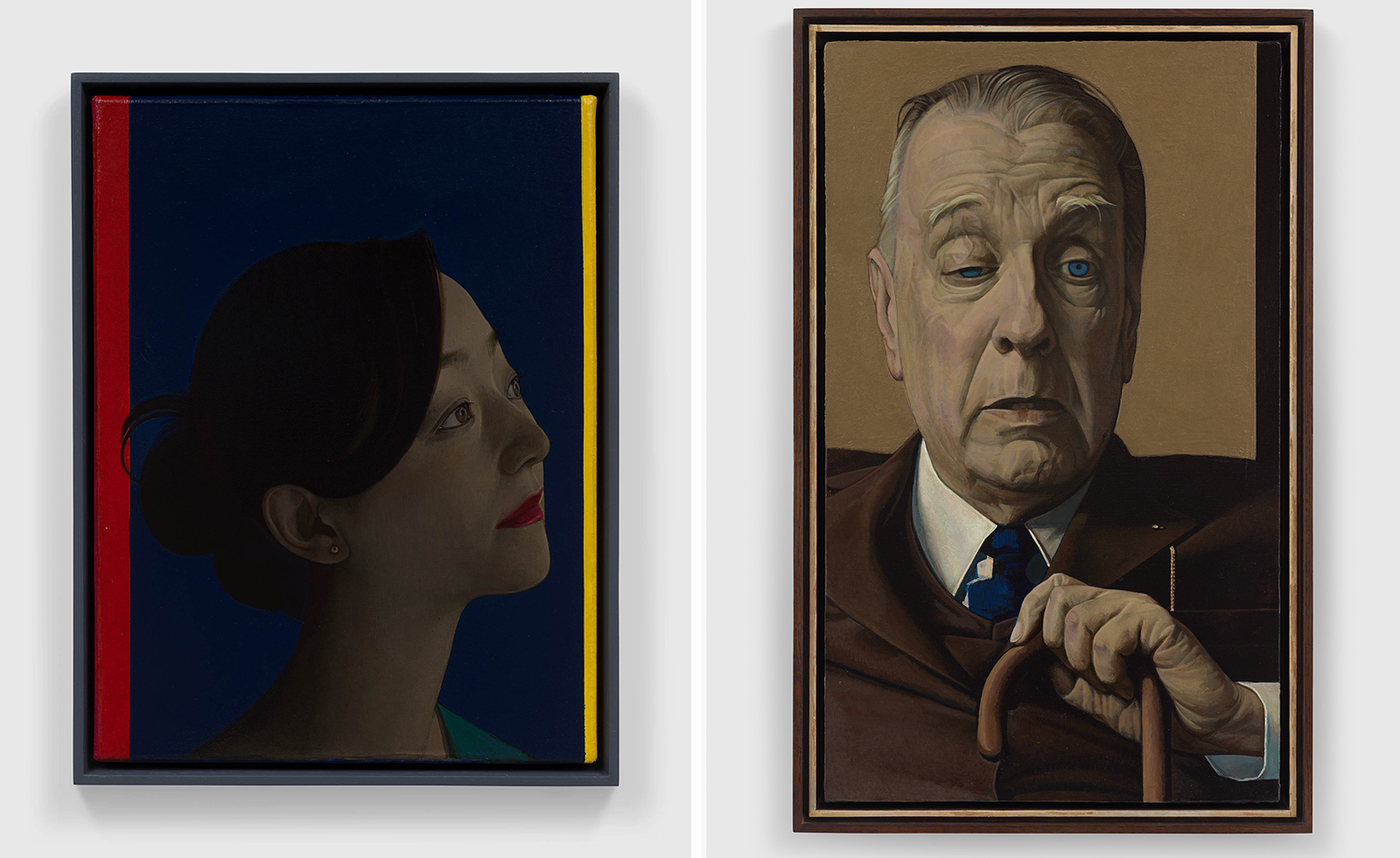

I hold deep gratitude for these remarkable translators, as their efforts have enabled me to explore literary works beyond the confines of the Chinese language. Whether it be the works of Shakespeare, Nabokov, or Borges, there exist exquisite Chinese translations of their masterpieces. I agree with this perspective: translation itself is a creative act. In the process of crafting this series of portraits, I envisioned myself as both a creator and a translator. The source material consists of historical photographs taken by photographers, while my role is to ‘translate’ them into paintings. When painting portraits of Borges or Nabokov, I wanted to get as close as possible to how they looked in those historical photographs. Simultaneously, I acknowledged the vast temporal and spatial distance that separates me from them, leading me to realise that what I truly require is the ability to conjure them in my imagination – a certain imagination that bridges distances ‘with wings‘. Of course, I've also come to realise that capturing their true essence is an unattainable endeavour; everything remains akin to the reflection of the moon upon water.

W*: How has John Adams' symphony inspired you here, and how has this intertwining of cultural references enriched your work?

LY: I love music profoundly, yet I must confess that I can neither play any musical instrument nor read sheet music. My relationship with music differs from Kandinsky's connection between art and music. While I'm painting, I often listen to music, enjoying a diverse array of genres. Among these, I find myself most drawn to Bach, although I generally avoid Beethoven as his heroic style doesn’t resonate well with me. I am not a musician in any sense, so I approach music with a casual and relaxed demeanor, purely for the sake of enjoyment. I find this approach quite satisfying, and to some extent, I could be considered a ‘naive’ listener. In light of the current state of relations between China and the US, I revisited John Adams’ CD, Nixon in China, and interestingly, I found myself more captivated by the music than the narrative.

This prompted me to explore all available resources of Adams’ musical compositions, discovering that his style harmonises remarkably with my taste. He employs techniques such as repetition, variation, symmetry, references, irony, and more, all of which I deeply appreciate. In preparation for my upcoming exhibition in London, I drew inspiration from the title of Adams’ three-movement symphony, Naive and Sentimental Music, titling my show similarly and substituting ‘music’ with ‘painting‘. I feel this adaptation aptly conveys the essence of my work. Later, I learned that Adams’ music serves as a response to Schiller’s renowned essay, On Naïve and Sentimental Poetry. This seems to complicate the issue while my interpretation of ‘naive‘ and ‘sentimental’ remains rooted in their literal meanings, rather than engaging with Schiller’s aesthetic viewpoints. For me, Schiller’s approach is too theoretical.

W*: It is an eclectic choice of subject, from Nabokov to Miffy. How do you choose the portrait subjects?

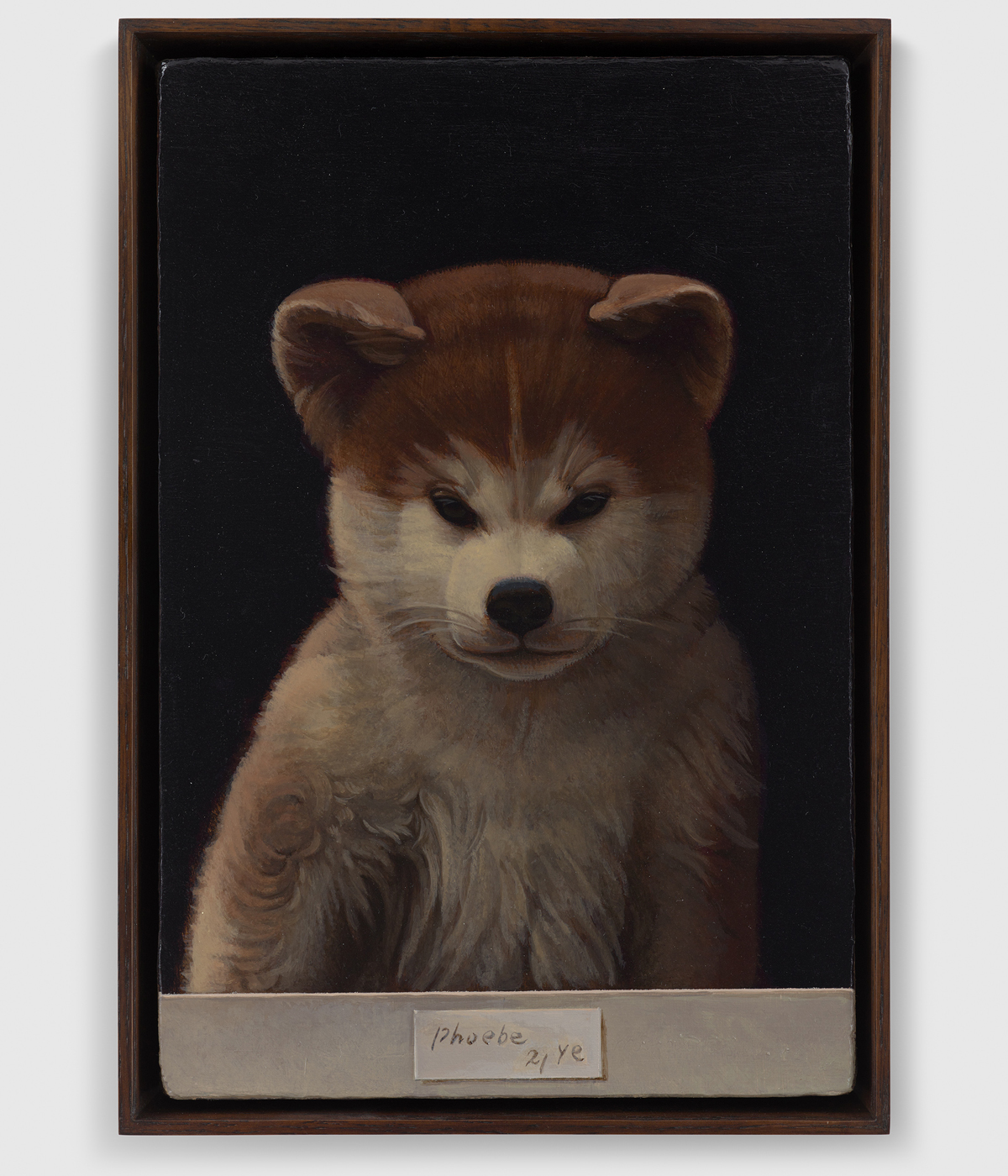

LY: I am deeply fascinated by the relevance of my subjects; they hold contextual connections that often do not unfold in an obvious linear manner, but more like lively leaps and, at times, even deceptive twists. Nabokov’s admiration for Carroll (the author of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland) inspired me to portray Miffy the rabbit, reminiscent of the childhood game of ‘hide and seek’. In contemplation of the limited span of our lives – much like Nabokov’s opening words in Speak, Memory: ‘...our existence is but a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness…’ – I exercise careful deliberation when selecting subjects for my portrait paintings. Only when his or her presence becomes a recurrent image, profoundly influencing my reality or inner world, do I consider depicting her or him.

W*: Can you talk about references to both Chinese and European references in your work generally, and in these new portraits for the London exhibition?

LY: In creating the portraits of Borges and Nabokov, I began by collecting hundreds of their photographic images, then I started with sketches and slowly refined the one image I envisioned in my mind, and after that, I’d move on to my working process of ‘translation‘.

The inspiration behind the portrait of Su Li-zhen comes from the character of the same name in Wong Kar-wai’s films In the Mood for Love and Days of Being Wild. The character of Su Li-zhen is portrayed by Maggie Cheung in both of these films. Therefore, this series of portraits serves as both a depiction of Maggie Cheung and the character Su Li-zhen.

W*: What is your daily working routine?

LY: I take pleasure in working in natural light, painting while listening to music, watching movies in the evening, reading before bedtime, and maintaining an orderly studio.

‘Naive and Sentimental Painting’ is on show at David Zwirner, London, until 18 November 2023