Many people see death as a rite of a passage: a journey to some new place, or a threshold between two kinds of being. Zoroastrians believe that there is a bridge of judgment that each person who dies must cross; depending on deeds done during life, the bridge takes the deceased to different places. Ancient Greek sources depict the deceased crossing the river Styx, overcoming obstacles with the help of coins and food.

But the dead cannot make this transition alone – surviving family or friends play key roles. Ritual actions the living perform on behalf of the dead are said to help the deceased with their journey. At the same time, these actions give the living a chance to grieve and say goodbye.

As a scholar of South Asian religions specializing in death and dying, I have seen how much surviving family depend on these rituals for peace of mind. Traditions vary widely by region and religious tradition, but all of them help mourners feel that they have given one last gift to their loved one.

Fire, water and food

Some Hindu death rituals have roots in ancient Vedic rites as old as 1,500 B.C.E. The survivors’ goal is to ensure that a dead person separates from the realm of the living and makes a safe transition to a blessed afterlife or rebirth.

Death rites typically use fire, water and food in a sequence of three stages.

Stage one is cremation, the fiery incineration of a corpse on a stack of wood infused with flammable oils. Cremation is considered the dead person’s willing, final gift to the god of fire, traditionally officiated by the oldest son of the deceased.

Stage two is the immersion of cremated remains in a flowing body of water, such as the Ganges River. There are many sacred rivers in India where the ashes of a loved one can be immersed, and Hindus regard them as goddesses who carry off impurities and sins, assisting the soul on its journey.

Many Hindus believe the ideal place to immerse a loved one’s ashes is in the sacred city of Varanasi, in northern India, where the Ganges flows in a broad stream. Families carry corpses in festive processions to the cremation site, hopeful that their rituals will help loved ones move to another state of existence.

Stage three is entrance into the realm of the ancestors. Ancient Hindu belief depicts relatives who have died living in a realm where they are maintained by offerings given by their living descendants, whom they assist with fertility and wealth.

Hindu beliefs and practices are extremely diverse. In many communities, however, descendants perform rites that offer nourishment to the dead person, represented in the form of a ball of rice. Through these offerings, which can be performed after the death or during certain holidays and anniversaries, the deceased spirit is said to gradually become an embodied ancestor, reborn thanks to the ritual labor of their offspring.

Colorful processions

Buddhist death rituals differ considerably from culture to culture, yet one commonality is the amount of human effort that goes into sending off the dead.

In Chinese and Taiwanese culture, it is thought best to send off the deceased with a well-attended funeral procession, full of pageantry for deities and mortals alike. Many people rent “Electric Flower Cars,” trucks that serve as moving stages for performers – even pole dancers are not uncommon. Fifty jeeps with pole-dancing women graced the funeral procession of a Taiwanese politician who died in 2017.

Though pole dancers are a newer phenomenon, Taiwanese funerals and religious processions have long showcased women and young people, including female mourners hired to wail. Scholars such as anthropologist Chang Hsun suggest that a combination of such traditions led to the inclusion of women dancing and singing in some modern funeral processions.

By the 1980s, scantily clad women were a fixture of rural Taiwanese funeral culture. In 2011, anthropologist Marc L. Moskowitz produced a short documentary called “Dancing for the Dead: Funeral Strippers in Taiwan” about the phenomenon.

Funeral performances show tremendous freedom and innovation; one sees drummers, marching bands and Taiwanese opera singers. Paper objects in the shape of things the deceased is believed to use in the afterlife are burned, from microwaves to cars. Likewise, specially printed money called “ghost money” is burned to provide the deceased with funds.

Guiding the dead

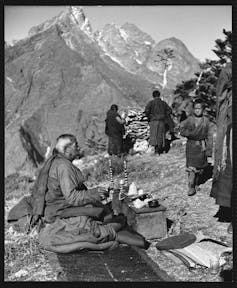

In Tibet, Buddhists believe that the vital energy of a person who has died stays with the body for 49 days. During this time, the dead person receives instruction from priests to help them navigate the journey ahead.

This journey toward the next stage of being involves a series of choices that will determine the realm of their rebirth – including rebirth as an animal, a hungry ghost, a deity, a being in hell, another human being or immediate enlightenment.

Priests whisper instructions into the ear of the dead person, who is believed to be capable of hearing so long as they retain their vital energy. Being told what to expect after death allows a person to face death with equanimity.

The instructions given to the dead are described in a sacred text called the “Bardo Thodol,” often translated in English as “The Tibetan Book of the Dead.” “Bardo” is the Tibetan term for an intermediate or in-between state; one might think of the bardo of death as a train that stops at various destinations, opening doors and giving the passenger opportunities to depart.

Tibetan Buddhists believe that these instructions allow the deceased to make good choices in the 49-day interim between their death and the next life. Different rebirth realms will appear to the person, taking the form of colored lights. Based on the karma of the deceased, some realms will seem more alluring than others. The person is told to be fearless: to let themselves be drawn toward higher realms, even if they appear frightening.

For several days before burial, the deceased is visited by friends, family and well-wishers – all able to work out their grief while assisting the dead in a postmortem journey.

Liz Wilson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.