France's treasury plans to borrow a record €310 billion on the markets in 2026 – even though it is set to start the year without a fully voted state budget. The move underscores how unprecedented debt and persistent deficits are colliding with a fragmented parliament and a president already focused on the high‑stakes 2027 election.

As a result of the parliament's failure to vote the 2026 budget, France's government was forced to invoke a special emergency budget law that rolls over the previous year’s budget to keep the state funded when a new finance bill has not been adopted.

The same type of emergency legislation was used ahead of the 2025 budget, which was only finalised in February after being forced through parliament, a delay that cost the government €12 billion.

Bank of France governor Francois Villeroy de Galhau has cautioned that carrying over the 2025 framework into 2026 would lead to “a deficit far higher than desired” – a warning that temporary fixes risk worsening France's financial situation.

Why €310 billion more?

According to the budget bill the Treasury presented to the government in October, France needs to raise just over €305 billion in 2026 – slightly more than in 2025 – to keep the state running and pay back part of its existing debt.

Under a funding plan unveiled earlier this week, that will be done by selling about €310 billion in government bonds – in other words, by borrowing money on the financial markets for several years at a time.

The extra borrowing is mainly because more old loans are coming due. Repayments on past borrowing will increase from €168 billion in 2025 to nearly €176 billion in 2026, while the annual shortfall between what the state spends and what it takes in – the budget deficit – is still expected to total some €124 billion.

On top of that, the cost of servicing the debt is rising as higher interest rates feed through, partly as a result of France's credit rating sliding downwards.

Lower credit ratings

Paris is starting to feel the effects of downgrades and negative outlooks from the big credit‑rating agencies, which act as referees for investors when they judge a country’s debt.

In recent years, Moody’s, S&P and Fitch have all warned that high and rising debt, political tensions over reforms and repeated budget slippages make France a riskier bet than before, even if it remains firmly in investment‑grade territory.

Overseas investors hold more than half of France’s tradeable government debt, leaving the country more exposed if confidence wobbles and markets start demanding higher rates.

The amount the state pays just in interest is set to jump from €52 billion in 2025 to more than €59 billion in 2026 – money that cannot be used for schools, hospitals or investment, and still does nothing to shrink the overall debt.

France faces credit downgrade as Moody's readies verdict on €3.2 trillion debt

In the EU's bad books

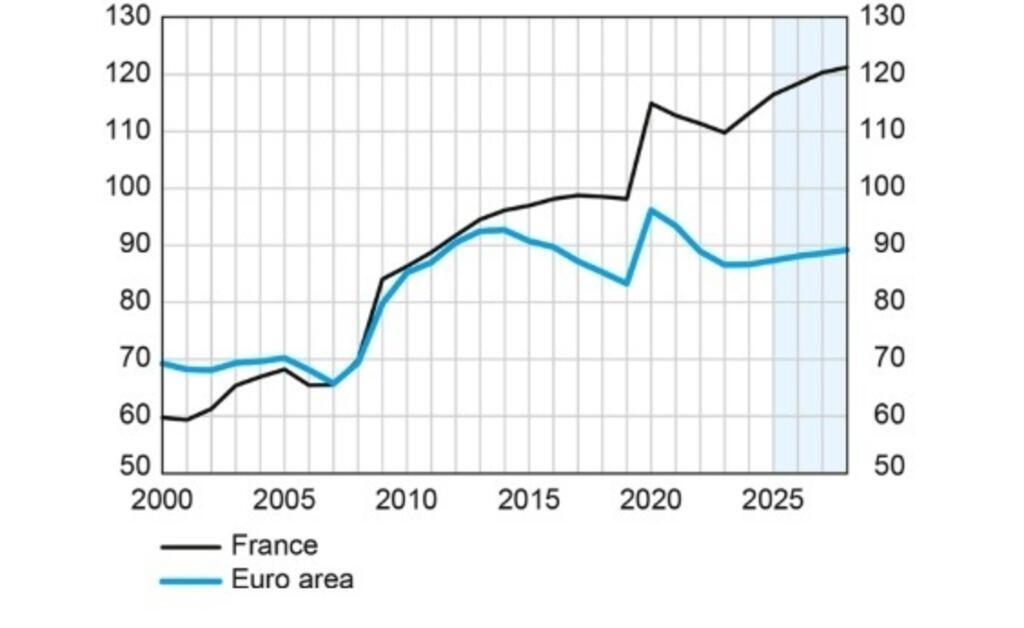

Meanwhile, with a staggering €3.2 trillion, France’s public debt has risen from around 97.4 percent of GDP in 2019 to more than 112 percent in 2023, placing it among the most indebted countries in the euro area and well above the 60-percent ceiling in the EU’s Stability and Growth Pact.

Germany's debt, by contrast, stands at around 62 percent of GDP, roughly half the French level, while the euro‑area average is below 90 percent.

Deficits have also widened. France moved from a government deficit of 2.1 percent of GDP in 2019 to about 4.9 percent in 2023 and remains in primary deficit, meaning it still borrows even before interest payments – unlike Germany, which has moved much closer to balance.

France is now the EU’s third most indebted member, behind Greece and Italy, and faces renewed EU pressure as fiscal rules are phased back in.

France braces for economic judgment amid political turmoil and record debt

High public spending, low growth

Several factors push France into repeated large‑scale borrowing.

The country has a tradition of high structural public spending, notably on social protection, health and pensions, which successive governments have struggled to trim without triggering protests.

Covid‑19 and energy‑price crises have also left a costly legacy. President Emmanuel Macron vowed to do “whatever it takes” to shield households and businesses, leaving a permanently higher debt burden.

Meanwhile economic growth remains weak, held back by low consumer spending and investment, as well as lingering political uncertainty.

Slower economic growth means France must cut €10bn in public spending

Eyes on 2027 presidential election

France's budget impasse comes after an exceptionally turbulent political period that has seen Macron cycle through five prime ministers in his second term. It reflects the difficulties of governing with a parliament deadlocked between rival blocs, none of which has a clear majority.

Current Prime Minister Sébastien Lecornu remains under intense pressure from the president to secure the 2026 budget while navigating threats of no‑confidence votes from both left and right.

Political challengers are likely to exploit the fiscal crisis and Macron's lame-duck status ahead of the 2027 presidential elections by framing the debt and budget situation as a failure of the president's centrist movement.

The far-right National Rally may blame what they see as excessive spending as well as ties with Brussels, while vowing to cut immigration and welfare programmes but protect pensions at the same time.

Meanwhile the left-wing New Popular Front is poised to attack austerity and push for new wealth taxes to fund social spending.

Insurance boss breaks ranks with French business elite over taxing the rich

And Macron's centre-right allies such as Édouard Philippe are likely to demand discipline via pension tweaks and caps, as all sides leverage Macron's PM carousel and institutional distrust to boost their ratings in the opinion polls.

The lower house of parliament will resume examining a full budget bill in the coming weeks, with debates expected to reopen on 13 January. Both houses must agree on the text before it becomes final.

(with newswires)