This winter, tens of thousands of birders will survey winter bird populations for the National Audubon Society’s Christmas Bird Count, part of an international bird census, powered by volunteers, that has taken place every year since 1900.

For many birders, participating in the count is a much-anticipated annual tradition. Tallying birds and compiling results with others connects birders to local, regional and even national birding communities. Comparing this year’s results with previous tallies links birders to past generations. And scientists use the data to assess whether bird populations are thriving or declining.

But a change is coming. On Nov. 1, 2023, the American Ornithological Society announced that it will rename 152 bird species that have names honoring historical figures.

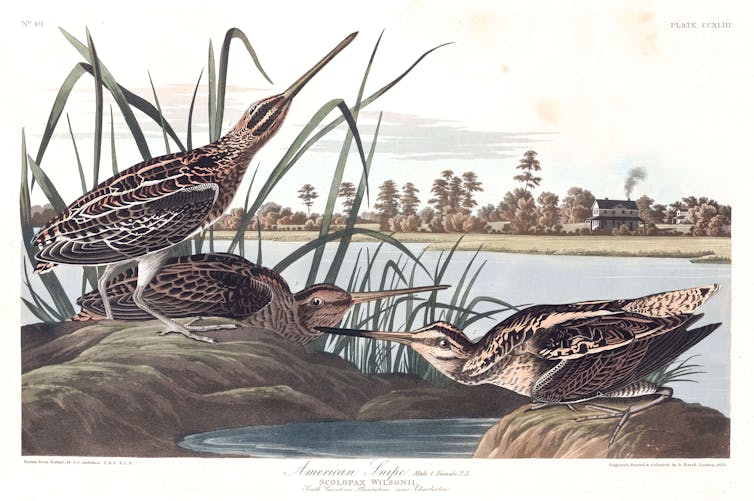

Soon, Christmas bird counters will no longer find Cooper’s hawks hunting songbirds. They won’t scan marshes for Wilson’s snipes. And here in Colorado’s Front Range, where I’ll participate in a local count, we’ll no longer encounter one of my favorite winter visitors, Townsend’s solitaires.

New names will take the place of these eponymous ones. With those new names will come new ways of understanding these birds and their histories.

Names matter

In my time birding over the past decade, learning birds’ names helped me recognize the species I encounter every day, as well as the ones that migrate past me. So I understand that it may not be easy to persuade people to accept new names for so many familiar North American species.

But as a scholar of politics, culture and denial, I also know that language shapes our understanding of history and violence. This includes bird names, as I’ve learned through my ongoing research into one iconic species’ place in American culture: the Eastern whip-poor-will.

Eastern whip-poor-wills are nocturnal birds who nest in forests of the eastern U.S. and Canada. English colonialists named the species for their distinct, repetitive call, which sounds like a malicious command to inflict punishment: “Whip poor Will, whip poor Will, whip poor Will.”

This naming had consequences. Generations of poets and naturalists, like John Muir and Mabel Osgood Wright, associated the species with whippings. Their writings often tell us as much about 19th and early-20th century Americans’ views of morality and punishment than about this remarkable bird.

What’s wrong with eponymous names

The whip-poor-will’s name translates the species’ song, leaving room for interpretation. Eponymous names based on a specific person, like Audubon’s oriole or Townsend’s solitaire, are less descriptive. Even so, these names shape how people relate to birds and the history of ornithology.

Many of these names honor people, usually white men, who engaged in racist acts. For example, John James Audubon owned slaves, and John Kirk Townsend robbed skulls from Native American graves. Changing these names helps separate birds from this harmful, exclusionary history.

But for multiple reasons, the American Ornithological Society is changing all eponymous names, not just those linked to problematic historical figures. First, the organization decided that it did not want to make judgments about which historical figures were honor-worthy. Second, it recognized that all eponymous names imply human ownership over birds. Third, it acknowledged that eponymous names do not describe the birds they name.

Change as a constant

While birders certainly will have learning to do once these changes become official, change is a constant in how people relate to birds.

Consider the technologies birders use. In the early 20th century, binoculars became more affordable and readily available. As Texas A&M historian Thomas Dunlap has shown, this helps explains why birders now “collect” birds by spotting them, rather than by shooting them, as Audubon and others of his time did.

Field guides, too, have come a long way. Early guides often relied on dense written descriptions. Today, birders carry compact, smartly illustrated guides, or we use smartphones to check digital guides, share sightings and identify birds from audio recordings.

Names, too, have long been open to revision. When the American Ornithological Union, the predecessor of today’s American Ornithological Society, created an official list of bird names in 1886, it erased untold numbers of Indigenous names, as well as local folk names.

Since then, some names have come into use and others have fallen out of fashion, especially as ornithologists lump and split species. Consider the ongoing adventure of just one species: Wilson’s snipe, a round marsh bird whose name will be among those changed.

In the American Ornithological Union’s original checklist of North American birds, Wilson’s snipes were a distinct species from the Common snipes of Europe and Asia. Then, in the mid-1940s, the Union decided the two were one, and Wilson’s snipes became Common snipes. In 2000, the Common snipe was split back into two species, and Wilson’s snipes again became Wilson’s snipes.

Either way, many early accounts of the North American species simply call these birds “Snipes.” This is the name Alexander Wilson, for whom the bird is named, himself used in his account of them.

Names reflect new knowledge and values

Science has greatly expanded human understanding of birds in recent decades. We now recognize that birds are intelligent, with rich emotional lives. Radar, lightweight transmitters and satellite telemetry have helped scientists map the transcontinental migrations that many bird species make each year.

Trading eponymous names, which treat birds as passive objects, for richer descriptive names reflects this sea change in our understanding of avian lives.

Our thinking about race and racism has evolved dramatically as well. For instance, we no longer use folk names for birds based on racial and ethnic slurs, as Americans of the 19th and early 20th centuries did. The decision to change eponymous bird names reflects this shift.

It also reflects broader efforts to reckon with the legacies of racism and colonialism in our relationships with the natural world. There is increasing recognition that legacies of racism shape our natural landscapes. Just as public monuments can have “expiration dates,” so can names for species, geographic features and places that no longer reflect contemporary values.

Birders no longer live in Audubon’s world. We rarely consult his heavy, multi-volume folios. We celebrate that we list birds that we have seen in the wild and left unharmed, rather than collecting their bodies as specimens.

Soon, we’ll also stop using some of the names that this world gave to birds.

Jared Del Rosso does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.