Eli Lilly will cut prices for some older insulins later this year and immediately give more patients access to a cap on costs they pay to fill prescriptions.

The moves promise relief to some people with diabetes who can face yearly costs of more than $1,000 for the insulin they need to live.

Lilly’s changes come as lawmakers and patient advocates have been pressuring pharmaceutical manufacturers to do something about soaring prices.

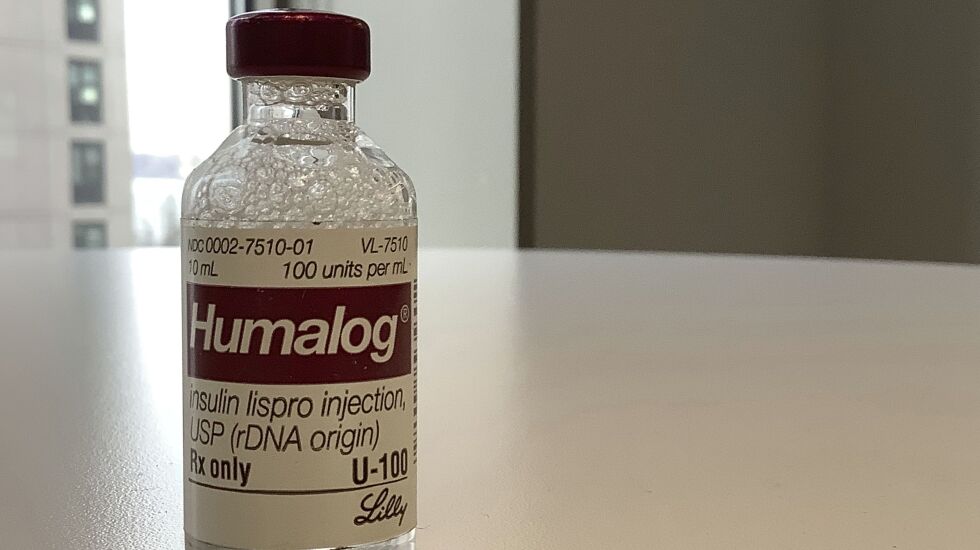

Lilly said it will cut the list price for Humalog, its most commonly prescribed insulin, and for another insulin, Humulin, by 70% in the fourth quarter of this year, which starts in October.

List prices are what a drugmaker initially sets for a product and what people who have no insurance or plans with high deductibles are sometimes stuck paying.

David Ricks, Lilly’s chief executive officer, said his company was making these changes to address issues that affect what patients pay for its insulins.

Ricks said that discounts Lilly offers from its list prices often don’t reach patients through insurers or pharmacy benefit managers. High-deductible coverage can lead to big bills at the pharmacy counter, particularly at the start of the year, when new deductibles haven’t yet been met.

“We know the current U.S. health care system has gaps,” Ricks said. “This makes a tough disease like diabetes even harder to manage.”

Patient advocates have long called for insulin price cuts to help uninsured people — people who wouldn’t be affected by price caps tied to insurance coverage.

Lilly’s planned cuts “could actually provide some substantial price relief,” according to Stacie Dusetzina, a Vanderbilt University health policy professor who studies drug costs.

Lilly’s moves probably won’t affect the company much financially because the insulins are older, and some already face competition, Dusetzina said.

Lilly also said it will cut the price of its authorized generic version of Humalog to $25 a vial starting in May.

And it’s launching a biosimilar insulin in April to compete with Sanofi’s Lantus.

Ricks said it will take time for insurers and the pharmacy system to implement the drugmaker’s price cuts, so Lilly will immediately cap monthly out-of-pocket costs at $35 for people who aren’t covered by Medicare’s prescription drug program.

The cap applies to people with commercial coverage and at most retail pharmacies.

Lilly said people without insurance can find savings cards to get insulin for the same amount at its InsulinAffordability.com website.

In January, the federal government began applying that cap to patients with coverage through Medicare, for people 65 and older or those who have certain disabilities or illnesses.

President Joe Biden, who brought up that cost cap during his annual State of the Union address, calling then for insulin costs for everyone to be capped at $35, tweeted in response to Lilly’s moves: “Today, Eli Lilly is heeding my call. Others should follow.”

Huge news.

— President Biden (@POTUS) March 1, 2023

Last year, we capped insulin prices for seniors on Medicare, but there was more work to do.

I called on Congress – and manufacturers – to lower insulin prices for everyone else.

Today, Eli Lilly is heeding my call. Others should follow. https://t.co/Kv57KFATe9

Chuck Henderson, the chief executive officer of the American Diabetes Association, also called on other insulin makers to cap patient costs.

Aside from Eli Lilly and the French drugmaker Sanofi, other insulin makers include the Danish pharmaceutical company Novo Nordisk.

Neither company responded to a request for comment.

Insulin is made by the pancreas and used to convert food into energy. People who have diabetes don’t produce enough insulin.

People with Type 1 diabetes must take insulin every day to survive. More than eight million Americans use insulin, according to the American Diabetes Association.

Prices for insulin have more than tripled in the past two decades, and pressure has been growing for drugmakers to help patients.

The state of California plans to explore making its own, cheaper insulin. Drugmakers also might face competition from companies like the nonprofit Civica, which plans to produce three insulins at a recommended price of no more than $30 a vial, a spokeswoman said.

Drugmakers could be seeing “the writing on the wall that high prices can’t persist forever,” said Larry Levitt, an executive vice president with the nonprofit Kaiser Family Foundation, which studies health care. “Lilly is trying to get out ahead of the issue and look to the public like the good guy.”

Ricks said that Lilly made the changes “because it’s time and it’s the right thing to do.”

In 1923, Eli Lilly and Co., based in Indianapolis, became the first company to commercialize insulin. That was two years after University of Toronto scientists discovered it. The drugmaker built its reputation around producing insulin even as it branched into cancer treatments, antipsychotics and other drugs.

Humulin and Humalog and its authorized generic brought Lilly revenue of more than $3 billion last year and more than $3.5 billion the year before that.

“These are treatments that have had a really long and successful life and should be less costly to patients,” Dusetzina said.