Research Checks interrogate newly published studies and how they’re reported in the media. The analysis is undertaken by one or more academics not involved with the study, and reviewed by another, to make sure it’s accurate.

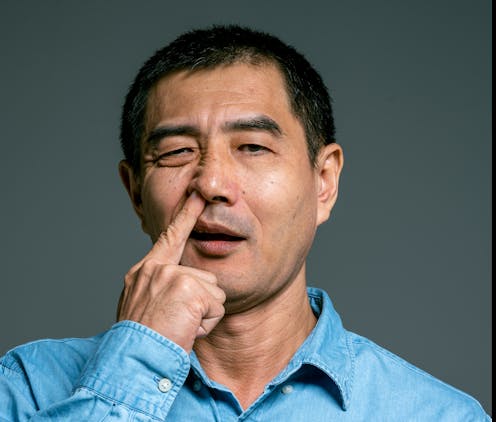

No matter your age, we all pick our nose.

However, if gripping headlines around the world are a sign, this habit could increase your risk of Alzheimer’s disease, the most common form of dementia.

One international news report said:

‘SCARY EVIDENCE’ How a common habit could increase your risk of Alzheimer’s and dementia

Another ran with:

Alzheimer’s disease risk increased by picking your nose and plucking hair, warns study

An Australian news article couldn’t resist a pun:

Could picking your nose lead to dementia? Australian researchers are digging into it.

Yet if we look at the research study behind these news reports, we may not need to be so concerned. The evidence connecting nose picking with the risk of dementia is still rather inconclusive.

Read more: What causes Alzheimer’s disease? What we know, don’t know and suspect

What prompted these headlines?

Queensland researchers published their study back in February 2022 in the journal Scientific Reports.

However, the results were not widely reported in the media until about eight months later, following a media release from Griffith University in late October.

The media release had a similar headline to the multiple news articles that followed:

New research suggests nose picking could increase risk for Alzheimer’s and dementia

The media release clearly stated the research was conducted in mice, not humans. But it did quote a researcher who described the evidence as “potentially scary” for humans too.

Read more: Is this study legit? 5 questions to ask when reading news stories of medical research

What the study did

The researchers wanted to learn more about the role of Chlamydia pneumoniae bacteria and Alzheimer’s disease.

These bacteria have been found in brains of people with Alzheimer’s, although the studies were completed more than 15 years ago.

This bacteria species can cause respiratory infections such as pneumonia. It’s not to be confused with the chlamydia species that causes sexually transmitted infections (that’s C. trachomatis).

The researchers were interested in where C. pneumoniae went, how quickly it travelled from the nose to the brain, and whether the bacteria would create a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease found in brain tissue, the amyloid β protein.

So they conducted a small study in mice.

The researchers injected C. pneumoniae into the noses of some mice and compared their results to other mice that received a dose of salty water instead.

They then waited one, three, seven or 28 days before euthanising the animals and examined what was going on in their brains.

Read more: Of mice and men: why animal trial results don’t always translate to humans

What the study found

Not surprisingly, the researchers detected more bacteria in the part of the brain closest to the nose in mice that received the infectious dose. This was the olfactory brain region (involved in the sense of smell).

Mice that had the bacteria injected into their noses also had clusters of the amyloid β protein around the bacteria.

Mice that didn’t receive the dose also had the protein present in their brains, but it was more spread out. The researchers didn’t compare which mice had more or less of the protein.

Finally, the researchers found that gene profiles related to Alzheimer’s disease were more abundant in mice 28 days after infection compared with seven days after infection.

How should we interpret the results?

The study doesn’t actually mention nose-picking or plucking nose hairs. But the media release quoted one of the researchers saying this was not a good idea as this could damage the nose:

If you damage the lining of the nose, you can increase how many bacteria can go up into your brain.

The media release suggested you could protect your nose (by not picking) and so lower your risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Again, this was not mentioned in the study itself.

At best the study results suggest infection with C. pneuomoniae can spread rapidly to the brain – in mice.

Until we have more definitive, robust studies in humans, I’d say the link between nose picking and dementia risk remains low. – Joyce Siette

Blind peer review

Nose picking is a life-long common human practice. Nine in ten people admit doing it.

By the age of 20, some 50% of people have evidence of C. pneumoniae in their blood. That rises to 80% in people aged 60-70.

But are these factors connected? Does one cause the other?

The study behind these media reports raises some interesting points about C. pneumoniae in the nasal cavity and its association with deposits of amyloid β protein (plaques) in the brain of mice – not humans.

We cannot assume what happens in mice also applies to humans, for a number of reasons.

While C. pneumoniae bacteria may be more common in people with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease, association with the hallmark amyloid plaques in the mouse study does not necessarily mean one causes the other.

The mice were also euthanised at a maximum of 28 days after exposure, long before they had time to develop any resultant disease. This is not likely anyway, because mice do not naturally get Alzheimer’s.

Even though mice can accumulate the plaques associated with Alzheimer’s, they do not display the memory problems seen in people.

Some researchers have also argued that amyloid β protein deposits in animals are different to humans, and therefore might not be suitable for comparison.

So what’s the verdict?

Looking into risk factors for developing Alzheimer’s is worthwhile.

But to suggest picking your nose, which introduces C. pneumoniae into the body, may raise the risk of Alzheimer’s in humans – based on this study – is overreach. – Mark Patrick Taylor

Mark Patrick Taylor works for the Environment Protection Authority (EPA) Victoria. He is the Executive Director of EPA Science and is also Victoria's Chief Environmental Scientist.

Joyce Siette does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.