The debut podcast dropped just before Valentine’s Day 2022. Katie Meyer recorded it inside a conference room on Stanford’s campus, alongside her father, Steve. This episode, she hoped, would capture the desired tone of future editions of Be the Mentality. She’d feature young, ambitious, accomplished athletes and anyone who supported their aims.

Katie called her dad “my guy” as she walked through his life. From small-town Iowa, a college deejay and three-time state horseshoes champion, he met her mother in college at a Greek mythology final.

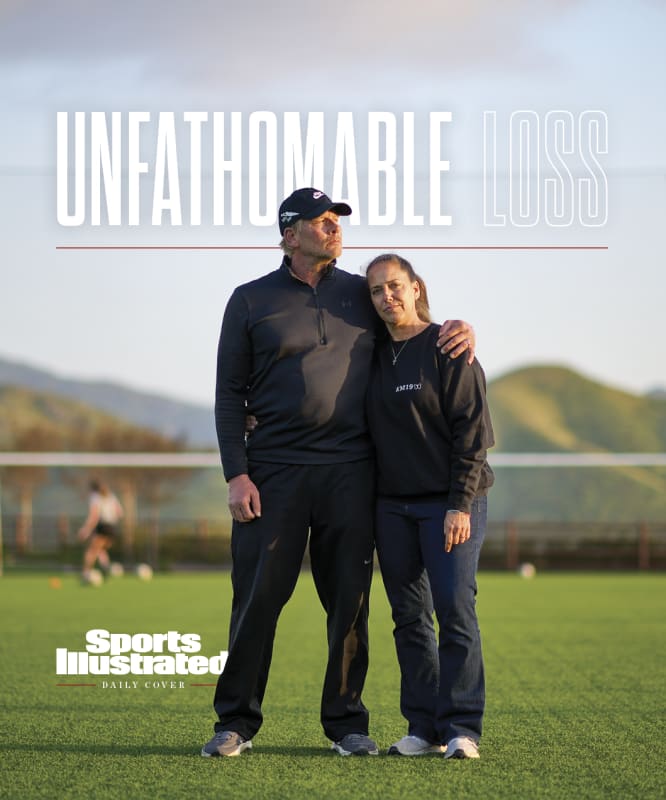

Kohjiro Kinno

“Did you study?” Katie asked.

“I studied her.”

“Ewwwwww, gross!”

The podcast sounds heavier now, over a year later, as Steve watches clips on his iPhone. His legs shake involuntarily, and tears form in his eyes.

Deeper in the episode, Katie turned toward youth soccer. The Cardinal goalie wanted to make U.S. national teams so badly as a teenager that she perpetually left family, friends and schools to attend tryout camps. “That creates such an interesting perception of reality in your mind,” she said. The competitive crucible split her life into two separate worlds. One: soccer star and honors student at Newbury Park High in Thousand Oaks, Calif. The other: elite but late-blooming USWNT hopeful. Not making a U-17 World Cup team marked the greatest disappointment of her life.

“I thought my world was ending ... crashing down. ... I’m the biggest failure ... so ashamed and terrified, because my entire identity was being ‘that’ soccer player,” she said.

Katie came from a family that didn’t do anything halfway, that lived and loved, its impact spreading all over Southern California. The exchange that night on the “Middle Daughter + Parents” group chat, all thank you and love you and heart emoji,

was proof of the bonds forged through endless activity.

Near the episode’s end, Katie pulled out a letter Steve had written two years earlier, on the eve of college soccer’s national semifinals. When Stanford advances that far in the postseason, its coaches invoke a tradition, asking parents to write to their children.

Steve watches now on his phone as Katie, on the podcast, began to read his letter out loud. He starts to cry. He looks thinner, lighter and happier in the video. He watches himself tell Katie that, no, life is not easy; players need supporters, advocates, champions to navigate social media negativity, outsized expectations and existences barreling so fast, in so many directions, that there’s no time to breathe. “Someone has to be a net,” she said, reading her father’s words.

She asked for one final nugget of wisdom. His answer: After failing, continue to move forward, however unsteadily, with an open mind. Unforeseen opportunities will roll in.

At that moment his words seemed charming, like sound advice. Today, they’re haunting. Katie never recorded another episode.

Two weeks later, she died by suicide.

The morning of Tuesday, March 1, 2022, began like any other in the Meyer household. Steve grabbed coffee and took the dogs out. For 25 years, he had worked in Hollywood, starting as a production assistant before rising to writer for shows like Everybody Loves Raymond and Hannah Montana. When COVID-19 halted the entertainment industry, Steve picked up an Uber Eats delivery gig. On this morning, before getting in his dented, messy, light-blue Prius, he partook in a favorite ritual: sending video of two scrambling, panting dogs to the “Smart Family” group chat.

Away at Stanford, Katie always found time to reply to these texts, even if only with a heart emoji. But today she did not.

She must be really busy, thought Gina, her mom. They knew she was. Everyone did. Ambition powered Katie. Stanford senior. Starting goalkeeper. Team captain. Not to mention: honors student with plans to attend law school. She applied only to Stanford.

The family had spoken to Katie the night before, over FaceTime. She complimented her younger sister Siena’s makeup and updated Gina on the previous week. She was recovering well from a recent knee surgery . . . anticipating her spring break in Tulum, Mexico . . . enrolling in classes for her final college quarter the next day. Older sister Samantha, a teacher, rushed in and announced her car had been broken into. Steve made a wave-hello cameo between drop-offs. All saw Katie as Katie: happy, vibrant, juggling, capable.

As Steve waited for the text response that never came, he had a premonition. He had them regularly, sometimes about Katie. He would feel an urge to drive to Stanford and check in. This time, the impulse felt stronger. He parked in front of Sally Beauty, a supply store near their home. His cellphone buzzed. He didn’t answer. It buzzed again. Same number. Ignore. When it buzzed once more, he picked up. It was Katie’s friend from Stanford, and he was so hysterical Steve could hardly understand him. But two words cut through.

“She’s gone!” the friend screamed, over and over.

John Hefti/USA TODAY Sports

To piece together Katie’s story, Sports Illustrated spent dozens of hours with the Meyer family; reviewed hundreds of pages of documents; interviewed more than a dozen of her teammates, coaches and friends; and spoke with experts on mental health and college discipline. The findings raise important questions about how Stanford dealt with its star goalkeeper and whether its policies hurt its students.

The Meyers’ search for answers started on the day she died, as a handful of teammates and friends began to fill in Steve and Gina. Katie had hidden an incident from her family for months. It started with a teammate alleging that she had received an unwanted kiss from a football player on Aug. 20, 2021. Then, according to court documents and confirmed in several interviews, eight days later, Katie happened by the football player while riding her bike through campus, and she spilled hot coffee on him. Katie, in her communications with Stanford’s Office of Community Standards (OCS), said she fell off her bike and that the spilled coffee was an accident—that she didn’t know the person it landed on. But according to a letter from Stanford’s disciplinary arm, the football player said she had intentionally poured it on his back. On Sept. 16, the OCS launched an investigation. Katie was informed the next day. The office interviewed her shortly afterward—and began talking to others as well.

A fleeting incident had suddenly morphed into a major issue. The investigation, one teammate says, instilled fear that “everything Stanford meant to her would be taken away.”

In the wake of Katie’s death, Steve and Gina found communication from the school lacking. They say they had trouble accessing Katie’s records and were put off by the clinical tone of Stanford’s statements. But that disappointment paled in comparison to their shock over what they would learn about Stanford’s disciplinary process.

The family filed its complaint against Stanford, and a number of its officials and administrators in Santa Clara Superior Court on Nov. 23, 2022, seeking injunctive relief and damages for, among other charges, wrongful death. Stanford declined to comment to SI but has declared in legal filings and in a news release that “we strongly disagree with any assertion that the university is responsible for her death.” (The school has also denied communication lapses with the Meyers and said it worked with them on statements about Katie.)

Now, the central argument in case No. 22CV407844 will play out in court: Did Stanford, Katie Meyer’s oasis, the engine for her driving ambition and home for most of her final four years, fail her?

Gina gave birth to Katie, the second of three daughters, in 2000. Right away, Katie struck both her parents as fearless. She scaled tall trees and leapt off; transformed living rooms into obstacle courses; adored animals, Star Wars and Lego.

Gina taught her careful planning and tireless execution. Steve drilled protect the meek, a favorite phrase, and to be decisive and kind. Katie became a star goalkeeper and, for one season, a kicker on her high school football team. She embraced goofy excursions (afternoon tea, anyone?) and aced her classes. But nothing called to her like soccer.

She joined her first team at age 5, so determined—and so in love with The Lion King—that she sometimes literally roared at opponents. She moved to club soccer by 9 and switched from forward to goalkeeper. Soon she joined travel teams and state teams and qualified for the U-16 national team.

Her position fit Katie like the gloves that snuggled both her hands. She made diving stops and sprinted toward attackers, dismissing bruises and ripped skin and jammed fingers (and one broken toe). She wasn’t the tallest goalie, but she was quick, agile, athletic. “Born to play keeper,” says Steve, who also works as a private soccer coach. “The different textures of her personality folded into that position.”

When Katie was young, Steve once accidentally blasted her in the chest with a wayward shot. He stared back in amazement when she screamed, “That all you got?”

Soccer gave Katie purpose, popularity and acclaim. She fell for her future university on her initial visit, at age 15, carving an “S” into a pumpkin that Halloween. In Stanford, she saw all the spaces she planned to conquer. The soccer field. The classroom, where she planned to study international relations and one day become president of the United States. The campus, where she was endlessly involved.

For Katie, anything seemed possible. Especially at Stanford.

Courtesy of the Meyer Family

On that terrible Tuesday, Steve pointed the family north in their white SUV, destination Palo Alto, same as usual and like never before. The sounds in the car haunt still. Screams, sobs, deep breaths, hyperventilating, swearing, praying, comforting, questioning. The silent stretches were even worse, as four brains spun in four million directions. Steve hoped: Maybe everyone has it wrong. All considered the obvious yet unanswerable question.

Why didn’t she call me?

The next morning, the Meyers went to Katie’s dorm room, accompanied by a Stanford Student Care liaison. Bed, made; cellphone, laid next to her computer; everything clean and tidy. At that point Katie’s family knew what happened, but not why. The room, at first, provided little in way of clues.

They looked through her belongings: portable speaker, tapestry, small plants, pictures, coffee table, books, LSAT study guide. Looking back, they can see that this tiny room gave them unexpected gifts. “Like everything was her,” Gina says. “Her smell. Her vibe. Very . . . peaceful.”

They couldn’t grieve; there simply wasn’t time. Steve and Gina spoke in public, surrounded by hundreds holding candles on Stanford’s soccer field. They addressed Katie’s teammates privately, emphasizing that Katie loved them, saw them as warrior queens and sisters. When they cleaned out her locker, Siena nabbed a captain’s armband. She still carries it in her backpack.

The Meyers held a visitation that Friday at a local mortuary. With no time to plan, they limited the guest list to teammates, coaches and relatives. When the rest of the crowd departed, the immediate Meyer family stayed behind to say goodbye. Katie lay there, in a casket, clad in her Stanford soccer uniform. Each member of her family approached with a rose and placed it on her body. Some leaned in for a final hug. Gina followed Steve to the casket, rubbing Katie’s forehead and stroking her hair. This was the first time they had seen her body. Each family member kissed her forehead.

They didn’t finish packing until Monday, when they left campus, broken but still intact. Steve drove the rented U-Haul home, mind spinning. Katie’s ashes rested in a box below the passenger seat. Her remains were soon placed into necklaces for her sisters and spread off the Florida Gulf Coast and in her grandfather’s backyard outside Chicago. They will be taken on family trips, whenever those resume, and dispersed in Katie’s favorite park, near the Stanford campus and at a beloved beach where she surfed.

Erick W. Rasco/Sports Illustrated

Stanford’s Office of Community Standards operates as the school’s disciplinary arm for most cases. It is run by administrative staff who investigate and prosecute cases, while a panel of faculty, students and staff sit in judgment.

The Meyers’ complaint against Stanford echoes many other criticisms of its disciplinary arm and the school’s pressure-cooker atmosphere. In 2019, the student newspaper, the Stanford Daily, reported that a psychiatric ward near campus admitted between one and three students a week. From ’19 to now, at least nine Stanford students have died by suicide.

Two independent analyses—from the Student Justice Project (2012), a group of Stanford students, parents and alumni, and the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (’20)—found a host of problems with Stanford’s disciplinary system, including slow response times and poor communication.

“It’s a system that presumes guilt,” says Bob Ottilie, a lawyer and one of the SJP founders. After issuing his report, at first privately to Stanford, his group met with school administrators. Officials engaged, Ottilie says, for seven months. But, he adds, “Literally, nothing changed.” In May 2013, the SJP started publicizing the report. It hammered the OCS for failing to provide due process and said its officers used their positions to intimidate students. Stanford responded by criticizing the study as flawed. So the SJP produced a second report in ’13, this time including 24 testimonials from students. Each described trauma, depression, anxiety and more born from the disciplinary process.

The SJP offered recommendations—like free representation for the accused—but Ottilie says the school met them with “hostility.” Stanford does allow for trained, independent advisers called “judicial counselors” to assist students. The counselors can be faculty, staff or students, but are not professionals. Ottilie thinks the advocates should be able to operate more like lawyers.

Katie did not choose to have a counselor. One student Ottilie represented told him that when he asked Stanford whether he needed a lawyer, an OCS official told him hiring one for representation would be “used against you.” (Stanford did not respond to questions about Ottilie’s statements.)

In 2019, Stanford created the Committee of 10 to review its Student Judicial Charter (drafted in 1896) and Honor Code (written in 1921). The committee filed an interim report in April 2021, about a year before Katie’s death. It contained many of the same findings about Stanford discipline, including that the process took too long, even for minor violations.

Hideki Nakada served as Stanford’s assistant coach and goalkeeper specialist from 2014 to ’21. Katie, he says, “was the epitome of what we wanted.”

Nakada understood why Katie viewed redshirting in her freshman season of 2018 as a personal affront. When he relayed the staff’s decision, she broke down, crying on the field. On the podcast, Katie said the moment reminded her of the national team she didn’t make. “I was ready,” she said. “Because if I put my mind to something, why not?”

She returned to Stanford the next summer and declared she would start. Her best friends on the team, Sierra Enge and Naomi Girma, liked her chances. Girma, now a U.S. women’s national team star, had met Katie years earlier, at a national team youth camp, and was “in awe of her boldness.” As the season began, Katie split the starting duties. She seized the gig full time midway through the year.

When the Cardinal advanced to the national semifinals in 2019, Steve sat down and wrote his letter. He started with the little girl whose father sat her on a giant picnic table at a dog park near their house. He did this for two reasons: so she could look out at the amazing world around her and so she could, if she wanted, sail through the air, into his arms. But maybe, he wrote, there was a third reason. That girl was developing her boldness, the trust she needed to leap.

That little girl is strong from the inside out, and she ... lives within you. Approach this weekend with the bold spirit of that little girl. Get way up on the picnic table. ... And then, yes, LEAP.

Katie sent him a text message: “Your letter made me cry.” He shot back three rows of eight heart emoji.

Stanford played rival UCLA in the semifinals. Katie had chosen the Cardinal over the Bruins, and the early goal she allowed opened a can of trash talk. UCLA star forward Mia Fishel called out, “It’s the keeper.” But in the 42nd minute, Katie stood in goal, between Fishel and the net. Fishel ripped a short, hard liner toward the bottom-right corner. Meyer inched left, then exploded that way, blocking the attempt with both hands. While the crowd roared, Meyer sauntered up to Fishel, eyes ablaze, blond ponytail bobbing. “Is it the keeper?” she asked. Stanford won 4–1.

Forty-eight hours later, before the national title game against powerhouse North Carolina, Katie delivered a speech to her teammates in their locker room. Her voice grew so loud the coaches could hear every word from the next room. Their destiny had already been written. They had toiled, survived and fought for this. All they needed to do was sign the document they’d already authored. At the crescendo, she yelled, “Make it official.” Teammates screamed and hollered. “I felt invincible,” Katie said on her podcast.

After a goal-less regulation and overtime, the game went to penalty kicks. Katie, naturally, felt calm. Nakada pulled her aside and reminded her, “This is why you came to Stanford.”

Hell yeah, it was.

“Remember?” Steve asked on her podcast. Of course. When she was 15 or so, the father of the other goalie from her first PK shootout came up to Katie after she won, expressing awe at how easily she guessed where attempts were headed. “I DON’T GUESS,” Katie responded.

Against the Tar Heels, she blocked the first attempt, diving right. With the teams still tied after five attempts each, she noticed the shooter’s hip shift before ball met foot. She dived left, blocking the shot. I DON’T GUESS, true as ever. She stalked toward the stands, thumping her chest. When a successful Stanford kick clinched the victory, Katie piled on her teammates. Then she took a moment alone, patting the grass beneath the goal and fighting back tears. She left her championship ring and replica trophy with her parents. That night, she took back to campus only one thing.

The letter her dad wrote. She would frame it.

Jamie Schwaberow/NCAA Photos/Getty Images

John Todd/ISI Photos/Getty Images

COVID-19 cost the Cardinal most of their 2020 season, with the team finishing its abbreviated schedule at an uneven 6-6-2. Katie vowed the next season would be different.

She dived more deeply into everything in her senior year. She hunkered down to study for the LSAT. She cofounded a cheering armada at Stanford sporting events, helping rebrand the student section as The Forest. She fought for LGBTQ rights as part of an advocacy group, Cardinal Pride, consisting mainly of athletes. She was one of four Cardinal athletes chosen to deliver a TEDx Talk and wanted to become the first keeper selected in the first round of the NWSL draft.

Katie dreamed out loud, her future divided into Act I (professional soccer), Act II (lawyer, specializing in international relations) and Act III (the presidential bid). Sometimes her most audacious ambition, becoming President Meyer, came across as a joke. But confidants knew she meant it.

From the day they dropped her off to that horrific morning in March 2022, Steve believed Katie had found her place at Stanford. The university appeared to agree. Her smiling face became the lead photograph on the Stanford Athletics Twitter page. After she died, the image came down.

Katie flew home for Christmas in 2021. She trained at her favorite park with her father and younger sister, sang carols, opened presents. She admitted to stress only once that anyone can recall, when mentioning her still-pending law school application. She visited London during that winter break. In her journal, she wrote: You’re living the dream. You’re in London, sitting in the most beautiful café in the park. . . . It’s a beautiful morning to be exactly where you are.

But Katie didn’t tell her family everything. They found out later that she had been required to check a box on that application divulging that she was involved in a disciplinary proceeding. In a formal statement to the OCS she had sent the previous month, she had written that she was “terrified an accident will destroy my future.” She had been “scared for months,” she added, “that my clumsiness will ruin my chances of leaving on a good note.”

She also addressed life as a female athlete at a school like Stanford, where, she wrote, “male athletes are untouchable, female athletes know one mistake can ruin everything.”

The football player alleged to have kissed her teammate without consent, it turns out, did not receive any discipline. (Sexual harassment and assault cases, like his, typically go before the Title IX office, not the OCS. Per U.S. government guidance, Title IX cases don’t move forward without survivor participation unless it is “clearly unreasonable” to drop the matter.)

Katie also described her assertiveness as demonized. A perfectionist, she had been terrified of making mistakes her entire life. No alcohol, no speeding tickets, no A- marks. “I have given everything to this school,” she wrote. “I love Stanford.”

On Nov. 12 she had met with Julie Sutcliffe, then the assistant director of sport psychology. Katie detailed elevating feelings of anxiety and depression, describing her mood as irritable, frustrated and down, according to Sutcliffe’s notes, referenced in the Meyers’ complaint against Stanford. Katie scheduled a follow-up for the next week but missed the appointment after oversleeping from exhaustion, according to the complaint. She also saw Francesco Dandekar, the university’s associate director of sport psychology. According to the lawsuit, on Nov. 22 she told him she “was experiencing increased depression symptoms associated with perceived failure and [she reported] suicidal ideations.” (Dandekar did not respond to a request for comment.)

Stanford’s policy is that conversations between its students and its psychologists are confidential. For confidentiality to be broken, there must be an imminent threat of harm to oneself or others. The judgment call would have fallen to Dandekar as to whether Katie had met that threshold and he should alert others at Stanford of her condition. Kim Dougherty, the Meyer family lawyer, says the family believes the situation merited reporting. “There should have been communication,” she says. “There are supposed to be flags within the system.”

The next day, the lawsuit says, Katie met again with Sutcliffe, describing “worsening anxiety and mood and increased depression” coinciding with her interactions with the OCS. The lawsuit also states that, at the same time, she was having trouble filling her prescription for an ADHD medication. Though it is uncertain whether Katie suffered from withdrawal symptoms from the drug, they can include feelings of depression and

increased anxiety.

After hanging up with her family on the evening of Feb. 28, 2022, Katie hopped on another FaceTime call, with Girma. They talked about which classes both should take, with enrollment starting the next day. Shortly after 7 p.m., Katie paused abruptly. She said to Girma, “Oh my god. They’re charging me.”

Katie hung up and continued reading the email that had landed in her inbox from the OCS dean telling her that she would shortly be receiving a “formal written notice” from her office. The charge: “Violation of the Fundamental Standard by spilling hot coffee on another student.” The notice ran five pages and listed potential witnesses in her case (some of whom have been redacted from the version that became public through court proceedings). Katie also had access to a case documents folder. According to the notice the OCS sent her, the folder included interview notes from meetings with both her and the football player as well as other interview notes and pieces of evidence (like text exchanges between the football player’s mother and his coach). None of these documents are public.

The Meyer family contends, in its lawsuit, that Katie consistently said the spill was an accident (and witnesses agreed). But Stanford was claiming in its notice that, according to its investigation, Katie had told others that she had dumped the coffee intentionally, to defend her teammate. The notice also said the football player had told investigators he believed the act was intentional, claiming that Katie briefly followed him on her bike, said something referencing the interaction with her teammate and seemed to be laughing as she rode away.

The notice said that violating Stanford’s fundamental standard of behavior could result in “removal” from the university. Per university policy, the college senior’s degree was put on hold, meaning that she could not graduate until the matter was resolved. Having redshirted, she still had soccer eligibility left and could have continued as Stanford captain if she were accepted to its law school. Now both those things were threatened.

Six months had passed from the day Katie learned of the OCS complaint to the night she received that letter. In that time, communication from the OCS was sporadic. Hearing little, Katie considered the saga over, according to four others at Stanford who knew her well. Administrators sent the formal OCS charge on the last day before the university’s statute of limitations would have closed the case. It was sent after hours, when offices that could help Katie deal with any aftershocks (fear, anxiety, dark thoughts) were closed.

Naomi R. Shatz, a lawyer at Zalkind, Duncan & Bernstein, in Boston, who represents students in similar cases, says Stanford’s actions reflect “very common” problems in school disciplinary systems. Specifically, Shatz cites the length of the case and the lack of communication between officials and Katie. She wondered to SI why Stanford did not at least notify her during normal business hours. Difficult messages should be delivered face-to-face, she says. In-person meetings allow disciplinary officials to gauge student reaction while giving immediate referrals for any counseling, treatment or support options available. The notice directed Katie to the “on-call dean” as a support resource. But that’s it.

“I’ve done a lot of these,” Dougherty says, “and I’ve not seen one other charge like this go out after hours.”

Katie replied immediately to the OCS, at 7:11 p.m., describing herself as “shocked and distraught.” Thirty-seven minutes later, the university sent back a message to schedule a meeting. Katie responded to the last email within a minute, selecting a time in three days.

From the moment Stanford’s formal written notice had arrived, Katie found herself unsettled and alone. All while she was juggling several other stressors: her surgery, the pandemic, her team’s difficult season, her law school application.

According to the lawsuit, a forensic analysis of her computer showed that Katie “frantically toggled back and forth” among the letter, case documents and one internet search: how to defend herself against a disciplinary complaint. Katie read and reread statements from the player she had confronted, his mother, teammates, athletic trainer and football coach David Shaw, the complaint says.

Often in the case of suicide, families spend decades searching for why. The Meyers think they have theirs. In some ways that helps. In others it makes it harder.

What was Katie feeling? Steve and Gina can’t go there. Sitting on their patio, Gina places a hand on her husband’s leg.

“That’s what I’m scared of,” he says. “To let that sit in your head and think about what she was feeling right before she made that impulsive decision.”

“I just ... I just ... I can’t.”

Yalonda M. James/San Francisco Chronicle/AP

Has anything changed at Stanford? A Los Angeles Times story in March 2022 reported that, in the preceding two years, the school had increased its clinical staff by 20%, and, following Katie’s death, promised to add more positions. Earlier this year, Stanford updated its honor code and judicial charter. The main headline had to do with how exams would be proctored, though. Ottilie has advised three students in their disciplinary cases since Katie’s death and says most of the changes are window dressing. He believes that Katie’s alleged offense was a relatively minor one and should have been handled in a lower-stakes environment than the OCS.

The Meyers wake up every morning and choose to fashion what they can from the same grim reality. All in, still. They speak to groups—high school teams, soccer clubs, college teams and students—and cite statistics. Like: 125 Americans die by suicide every day. Or: It’s the second-leading cause of death for ages 15 to 24. They remind college athletes that, while they’re considered adults at 18, their brains aren’t fully developed until around 25. Then they segue into Katie’s story, saying how it drives them and the work of their foundation.

Katie’s Save is an initiative based on the principle of choice. The foundation provides the resources and paperwork necessary to help students select an empowered advocate to represent them in medical, emergency, academic or, yes, school disciplinary matters.

If only Katie had that ... there’s the genesis. The Meyers want to hold Stanford accountable. They want the disciplinary system changed. They want to bludgeon stereotypes. But, more than anything, they want her back.

The Meyers amended their complaint to withdraw six of the eight initial counts in their lawsuit, but the core charge remains: wrongful death. In sum, the Meyers contend that Stanford’s disciplinary system drove Katie to a desperate act, and that the school had failed to care for her properly.

The case is currently plodding through the California legal system, as the Meyers seek discovery. The next court date, for a “Case Management Conference,” is in March.

Where they can’t go with Katie’s death propels Steve and Gina forward. They haven’t taken a break from their new mission since the day they returned from Palo Alto. The understanding between them is implicit and unsaid. Maybe they’re channeling her energy, her spirit.

“Maybe we’re supposed to be doing this,” Gina says. “Maybe Katie is passing the baton to us, like a sign from the universe.”

Sometimes, Steve thinks back to the day he and Gina dropped Katie off at Stanford as a freshman. They went for a walk around campus. Steve asked Katie for a selfie. He always did. She never said no, never seemed embarrassed. He pulled her close and wrapped her tightly. Letting go, he teared up.

His daughter comforted him. She always did that, too.

“Dad,” Katie said, “don’t be like that.”

“I can’t help it,” he said. “I’m so proud of you.”

He still heads to the park near their house that Katie loved, to manage his grief. Steve wants to go to that park now, so he does, with one dog tucked under his right arm and the other straining the leash in his left hand. It’s been nearly a year since that terrible Tuesday. His hair is long, on purpose, an homage to Katie. In the months ahead, Samantha will become pregnant with their first grandchild, while Siena will net another family soccer scholarship, from UCLA.

Steve and Katie spent hundreds of hours out here, forsaking fancier parks nearby for this field with chewed-up grass and dirt patches. Every time he visits, the memories return. The cones they set up for drills. The hill she ran for cardio.

Steve thought he’d never coach again. But he is, still. Like on the afternoon he rolled a soccer ball toward Siena for the first time since Katie’s death, then felt an intense vibration on the left side of his head. “It’s high-pitched, deep, rapid, confusing. Almost like a hummingbird went inside my ear.” When it ceased, a butterfly cruised by. Katie, right?

He’s pointing now. She did pull-ups over there. Set the speed ladder up over there.

The sun drops. He carved Katie’s initials into a tree, and they’ve taken on a green hue, a coincidence perhaps, but also the preferred color for mental health advocacy. In the same spot as always, he stares in the same direction.

Over the mountains of Los Padres National Forest.

Toward Palo Alto.

Toward Stanford.

And Katie.