The Environment Minister is asking local authorities to juggle food production and freshwater quality as climate change and population growth stretch vege supplies

Regional authorities working to improve freshwater management have been asked by the government to check whether their vege patches can grow with a view to keeping Kiwis fed.

Population growth and climate change are driving a desire to know how Otago - and other regions - rate in food resilience capacity.

However, the request comes as stricter rules over water quality and commercial usage are progressively being introduced.

“Among other issues, this summer’s extreme weather has highlighted the importance of a wide geographic distribution of fresh vegetable production so New Zealanders can continue to access healthy food options at a reasonable cost,” says Environment Minister David Parker in a letter to Otago Regional Council.

The question appears to be how will the council allow vegetable production to continue and expand at the same time as improving freshwater resources.

The council is working through a long-winded and fraught process of creating a new land and water regional plan, which will have a big effect on Otago irrigators.

Once signed off it will form part of the national policy statement for freshwater management 2020 (NPS-FM).

In March Parker gave the council a six-month extension to notify its proposed water plan by June next year, requiring it to report to him monthly.

The newly requested vege reports will be required each year for at least the next two years, with the first due on May 19.

Parker says the resilience of New Zealand’s food system will continue to be tested as the effects of climate change intensify.

The number of mouths to feed is another factor with New Zealand’s population forecast to grow eight percent in a decade, according to StatsNZ.

“There is uncertainty as to how plans in development under the NPS-FM will enable continuity for vegetable growing and expansion of the domestic supply in line with future growth of New Zealand’s population.”

Parker wants to know about any mechanisms the Otago council is developing that enable vegetable growers to practise crop rotation or movement of production - and associated discharges - from one property to another.

He also wants to know about planning that might allow expansion of the region’s total area of vegetable production, noting “this will almost certainly lead to an increase in nitrogen-related discharges and potentially other discharges”.

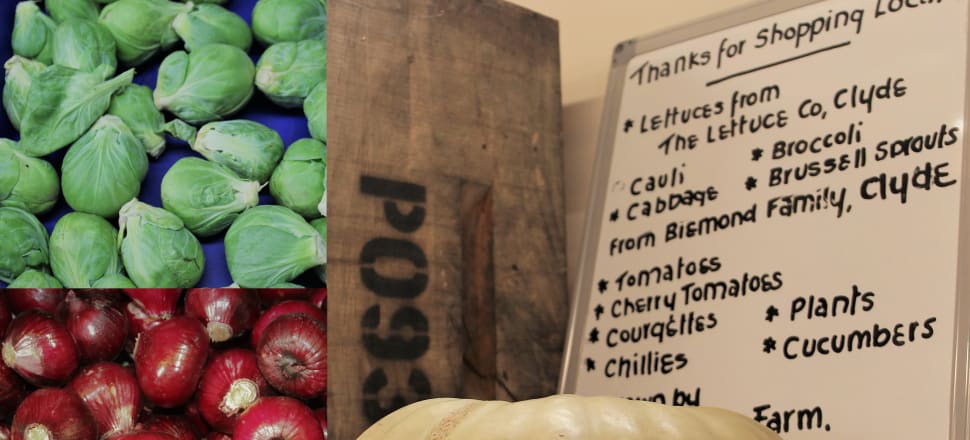

The bulk of Otago’s vegetables are grown in the north of the province around Oamaru, Palmerston and Kakanui, with Waitati, just north of Dunedin city, another productive patch.

Historically the Taieri Plains and Outram area have been big producers but much of that land has now been subdivided, according to a council report.

Environmental monitoring from 2000 to 2020 shows degrading trends for some water-quality parameters, including nitrogen, at various sites in North Otago and in tributaries of the lower Taieri River.

Councillor Michael Laws thinks the issue is more closely related to the loss of highly productive land to residential development than to freshwater management.

The former was dealt with through the government’s national policy statement on highly productive land introduced last October.

“This [ORC staff report] paper seems to link the request for vegetable statistics to freshwater - it’s got nothing to do with freshwater,” Laws said at a regional council meeting in Balclutha yesterday.

ORC chair Gretchen Robertson says the minister’s requirement for information, which was sent to 16 unitary and regional councils in New Zealand, relates to “potential” water-related issues.

“For example, councils that set a per hectare cap on nutrients could perhaps … be inadvertently making it difficult for vegetable production whereas if you looked at the area from a catchment load or a smaller type area it would be different.”

The challenge is to avoid unintended consequences for food production when setting irrigation water limits.

Not a pretty picture

Yesterday ORC’s environmental science and policy committee reviewed a new Ministry for the Environment report, “Our Freshwater 2023”, which concluded nationally freshwater resources are widely under pressure from both human activity and climate change.

Nationwide 46 percent of lakes larger than 1ha have been found to have poor or very poor health, according to computer-model estimates, the report states.

The amount of irrigated land in New Zealand almost doubled between 2002 and 2019 from 384,000ha to 735,000ha.

Over the same period 73 percent of increases in irrigated land area were related to farms, with dairy farming as the dominant farm type.

Eighteen percent related to growing grain, fruit, berries and vegetables and nine percent to sheep and beef production.

Models suggest such on-farm mitigation as fertiliser management and protecting waterways from livestock reduced the amount of phosphorus and sediment that reached rivers between 1995 and 2015, but not nitrogen.

“While the mitigations were estimated to reduce nitrogen losses from individual farms, this was not enough to offset the effects of the expansion of dairy and intensification of pastoral agriculture, which resulted in an increase in the nitrogen that reached our rivers during this period.”

Although some freshwater bodies remained in a reasonably healthy state, many have been degraded by the effects of excess nutrients, pathogens and other contaminants from land.

Made with the support of the Public Interest Journalism Fund