Over Danny Woodhead’s voice, every few minutes, came the sound of a club smacking a golf ball—that distinctive thwack! It was a Thursday in June, and the former NFL tailback was at his home course, the Omaha Country Club, a few weeks after falling one leg shy of qualifying for the U.S. Open. It was mid-afternoon, his round was done and he’d see his kids soon.

And that’s where I asked if, in the midst of this athletic rebirth, his eyes are on the PGA Tour.

“Honestly, that’s not really something that I’ve thought about a lot,” he answered. “I’ve just thought about trying to get better every year. Not surprising, after playing under Eric Mangini and Bill Belichick, I’m just trying to get better and see what happens … Or, I can’t say that, because if I was that good to where you know you should be there, then it’s hard to say no. But I love my life, Albert. I love being around my kids, I love being around my wife. There are so many years that I sacrificed time.

“And I knew that, and they knew that. Now, I love that I get to be at my kids’ events, I love being around my family. That’s what’s sick about golf, is you can try to compete and do different things, and as you get better, you can try to qualify for certain things and still do what you love.”

Over the next month, plenty of NFL players will play plenty of golf. Lots of guys can play a little. Woodhead, very clearly, can play a lot.

But in his answer to the question of whether he plans to try to go pro in a second sport—something that’s become more realistic with time, even if it still would be a big-time long shot—was lying the real wisdom that Woodhead’s found. Every year players leave the NFL like he did four years ago, after his March 2018 release from the Ravens. Every year, a big percentage of them struggle to deal with it.

That’s the thing about all this. On the day I called Woodhead, I figured we’d just talk about how he’s somehow who turned himself into a very legitimate threat to at least get tee times at golf majors. In talking to him, I figured out that, for his football peers, he has a lot more than that to give, and show, them.

The fact that he’s pretty damn good at his second sport is only a jumping off point for it.

Siragusa: Robert Hanashiro/USA TODAY NETWORK; Woodhead: Charles LeClaire/USA Today Sports; Gronkowski: Jonathan Dyer/USA TODAY Sports

As you read this, I’m (hopefully) shutting it down for a few weeks. And the NFL is already in vacation mode. So we’ll jump around a bit in this week’s MMQB column. In the column, you’ll find …

• A look into who Tony Siragusa was, as a personality and football player.

• More on Rob Gronkowski as he rides off into the sunset (for now).

• My take on Dan Snyder’s situation.

But we’re starting a little off-beat, with Woodhead’s unique story.

Woodhead started playing golf when he was 8 years old, with his dad and brother, went through high school with it, mostly stopped as he dove into college football, picked it up again his senior year at Chadron State and then played more after catching on with the Jets in 2008.

He never took a single lesson over all that time. To the trained eye, it showed.

In New York, kicker Jay Feely, safety Jim Leonhard, running back Leon Washington and punter Reggie Hodges were among those who’d get him out—and access to the best tracks in the area helped to fuel Woodhead’s growing curiosity. Feely was the leader of the group, connected in golf circles, and got them on to Trump National courses in Bedminster, N.J. and Westchester County, as well as Liberty National in Jersey City and Bayonne Golf Club.

A scratch golfer himself, Feely recognized Woodhead’s talent quickly, with the crew going out on Mondays, Tuesdays and Wednesdays during the Jets’ offseason program.

“It was so much fun playing with those guys,” Feely said. “And back then, he had this big rope hook, and we used to give him a hard time. … You could totally see [the talent] with him, but hitting with that big hook, it’s hard to score low.”

His first year on the Patriots, Woodhead dialed back his time playing. Then, before his second season in New England, the NFL locked out the players. Suddenly, he had a lot of time on his hands.

“I did get to a point the lockout year where I got pretty decent, probably close to a scratch—and I still hit it like a joker,” Woodhead said. “That was probably the year that I knew I had some sort of talent.”

Woodhead left the Patriots for the Chargers in 2013, and a confluence of weather, comfort level as a sixth-year pro (experience allowed him to balance football with other pursuits), and access to more golf and golf pros in Southern California positioned him to where, he says, “I caught the bug aggressively.”

While that was happening, then San Diego safety Eric Weddle took him out for a round and introduced him to a friend named Rick Johnson, who was a golf pro at the Country Club of Rancho Bernardo, 20 minutes north of the old Chargers Park practice facility and five minutes from Woodhead’s house. Johnson had worked with scores of pro golfers, and lots of weekend warriors too, and pretty quickly saw something with Woodhead.

He was barrel-chested (not ideal for a golfer) and had a funky form. He was also pretty good.

So as one round turned into a bunch, conversation advanced.

“The first thing was he scored so well for having such a poor golf swing,” Johnson said. “It was one of those things where he could score well because of his football qualities; he was a really crafty, smart player, and he had really good hands around green, a really good short game, and an extremely positive attitude. And I could tell he’d put the work in. We’d play a lot, and I wouldn’t help him too much, but we always talked about, Hey, when you retire, let’s just rebuild this whole thing and start from scratch.”

Which, as you’d expect, only brought out the competitor in Woodhead.

“I told my wife this, I was probably in Year 7 or 8, I said, Babe, when I’m finished, I wanna just see how good I can get at golf. I just wanna take some time and see if I can get good,” he said. “And honestly, that’s where we lie right now.”

That, of course, is underselling it quite a bit. In between then and now, a lot of things have happened.

On the golf side, Woodhead’s retirement from football triggered a detailed process that would require, among other things, a certain level of humility, and just as much determination.

Rebuilding Woodhead’s swing, for Johnson, meant taking it down to the studs. It meant, for a time, higher scores. It meant some 100-yard tee shots (“That’s the most embarrassing thing,” Woodhead said). It meant having patience and faith that looking bad for a little while would mean looking a lot better for a lot longer.

“There’s a thing in golf, it’s a rotary golf swing, you want to rotate your body,” Woodhead said. “I was lateral, so I would sway to the right side, sway to the left side, I wouldn’t swing around my body, like it’s meant to be. … So in some ways, it was a complete overhaul.”

With Woodhead’s old form, Johnson said, “The club doesn’t travel as far on the golf swing and your body doesn’t rotate. It’d be the difference between a jab and an uppercut. He was just purely a jab puncher, so to speak. So what we did, we were able to use his rotation and his fast-twitch muscles, by creating more room and space in his golf swing.”

The flip side to all of that was, in Johnson’s assessment, Woodhead had, at baseline, “incredible fast-twitch muscles, and he’s incredibly coordinated.” He also, being a pro athlete, was easy to coach. And not just because he wanted to get better, but because he could make his body do what Johnson was telling it to, and because he was detail- and process-oriented.

“My wife and I still joke about it,” Johnson said. “When Danny would call, I’d show her the phone, and say, I’ll be back in a half hour.”

As for the non-golf part of it? That’s even more interesting.

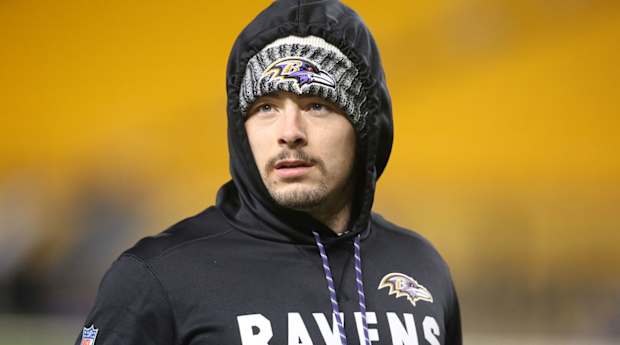

Charles LeClaire/USA TODAY Sports

This revelation stunned me a little bit. It came at the end of Woodhead’s four years in San Diego, just before he got to Baltimore and well before he and Johnson started serious work on turning Woodhead into more than just an awesome rec golfer.

“I asked God to take away the love of the game,” Woodhead said. “Because I’ve heard all those stats. I heard about all those guys that struggle in trying to find something to fill the void. And at the end of the day, even if I don’t have golf, there’s no void I have to fill. I have that in my faith. But I asked God to take away the love for playing football. … At the time, I was just praying that’s when I would know when I should retire. I didn’t want to leave still loving to play the game.”

Woodhead didn’t get what he’d asked for all at once. But during his last year, 2016 in Baltimore, as much as he liked the Ravens organization, there were little things that gnawed at him, almost as if the message was trickling through to him rather than coming like a flood. Meetings felt longer. The year did, too. And then after the season, that following March, the Ravens told him they were letting him go, but wanted to leave the door open for his return.

For a few days, Woodhead had vengeance on his mind—“I think all guys feel that, like, I wanna go sign with somebody that plays them.” Then, it hit him.

“I remembered what I’d been praying for,” Woodhead said. “And I really did have a love of the game—of playing it, not the love of the game, but the love of playing the game—taken. I was like, Wait a second, my prayer was answered. Why am I chasing this? Just because I’m mad, and I’m competitive and I got released?”

Four days after Baltimore cut Woodhead, he announced his retirement, and he, his wife, Stacia, son and three daughters started their new, different life in Omaha.

That, to be sure, doesn’t mean Woodhead completely cut himself off from football. He still watches and keeps track of his friends. He also knows that football gave him gifts that he still gets to open every day in his golf game.

In some ways, in fact, his drive to make it from Chadron State onto an NFL roster, and then on the field as a significant player, actually mirrors what’s motivating him in golf.

“I was probably around a five or six handicap when I retired, then I slowly got it down to close to a zero in that first year,” he said. “And I was like, Alright, I’ll try to get to the plusses. The next year, I make it into the pluses. And then, it’s like, I wanna keep going, go deeper, and then I went deeper. You keep taking these baby steps. I’ll be honest, there have been people that I know questioned me and talked and said different things to my face, or behind my back, saying, Oh, it’s so hard though, once you’re a zero, it’s hard to keep it there.”

Which, in many ways, is like someone patting a Div. II running back on the head for making it onto a roster, or carving out a role on special teams, while insinuating that’s enough.

“So you don’t think I’m gonna do it?” he continued. “And then I go deeper in the pluses and they’re like, Yeah, but that’s impossible. So in some ways, whether they were trying to be nice or not, it’s to set me up like, If you fail, it’s O.K. Every time someone’s said something like that to me, I knew they said that to me, and I kept it in the back of my mind.”

Of course, golf was perfect for more reasons than just scratching his competitive itch.

That much can be illustrated just by looking at his daily routine. Most days, Woodhead wakes up ahead of his family to work out, then makes breakfast for his kids. After that, he sees his girls and boy off to school. Then, he goes to his office—he and one of his best friends started Arise Ventures, a mergers-and-acquisitions business that helps small companies—for a couple of hours. If everything’s good there, with the ability to work through his phone if need be, he’ll go to the club to play a round or practice.

All of it allows him to get back in time to see his kids get home from school. So if you wonder why he doesn’t miss football, Woodhead will mention first, again, that his faith has really helped. But it’s also not like he has much time to think about it.

“Bro, if you ask me about my life, I’m having the time of my life,” he said. “I love being home. I loved competing, I thought I was having the time of my life living my dream when I was playing. And I was. But this side of the NFL is incredible. It’s the most amazing time I’ve been able to experience.”

As for Woodhead’s attempt to qualify for the U.S. Open, he got close, but not that close. He was 10-over at the Springfield (Ohio) Country Club (“Those events, they trick [the course] out, and it’s like, You better not make a mistake”) putting him well short of the scores posted by the eight players who made it out of the sectional to play in the Open.

That said, he was one-over on 32 of the 36 holes, and nine-over on four of them, so if he can clean a few things up …

“I didn’t play like trash,” he said. “But if you’re playing in an event like that, you gotta bring your best. If I would’ve brought my best, do I think I could’ve shot the number? Yes, I do. But I would’ve had to have my best. And I didn’t. So it’s one of those things, alright, go back to the drawing board, try to get better and see what happens next time.”

It also didn’t take him long to get back in the saddle—last week, he qualified for match play at the Nebraska Amateur, and was medalist (meaning he had the low score) at the event.

“That’s his Masters,” said Johnson. “Last year, he made the quarterfinals. This year, he was medalist in stroke play. And we’re joking, You’re not even the guy who played in the NFL that’s the good amateur player anymore. You’re the best amateur player in Nebraska now, straight up. And he goes, How do we expand that to the country?”

That’s where all the work Woodhead and Johnson did together comes into focus. When Woodhead would get frustrated as he and Johnson were going through the year and a half (or so) golf rebuild, and Woodhead would come back with higher scores than he was used to, the coach would insist, Just trust me, if you can make it through this, you can have 15–20 years of great golf. Let’s not shortcut it just so you can play good golf for a year.

The result is that Woodhead's ceiling has been raised considerably. The old football player used to hit his drives 240 or 250 yards. He’s now bombing it 330. From here, over time, Johnson says Woodhead will fine-tune how he manages himself in big tournaments—“It’s how you approach each shot, when you take risks, keeping momentum, nutrition on the round, how you prepare for events”—and that’ll make a difference, too. And of course, he’ll keep tightening up details, with more of those half-hour calls.

But the foundation is already in place.

“Phil Mickelson told me once … I asked him, What’s the most important thing you can have as a golfer? And I thought he’d tell me chipping or putting,” Johnson said. “He goes, speed, and not even for the reasons you’d think. He goes, Obviously, hitting a longer tee ball is important. But, all of a sudden, you have three, four less clubs into the green. … Danny has elite, tour-player speed now. I mean, elite. Not like, Yeah, oh, he hits it far for an ex-NFL guy. No, dude hits it legit as far as some of the longest guys on tour.”

And at this point, Johnson knows Woodhead’s game as well as his own. When they started, they’d visit in-person three times per year, once in San Diego, once in Omaha and once in Las Vegas (where Johnson works with Norman Xiong, a rising star in the sport whom Woodhead’s now mentoring). That fell off a little during COVID-19 times, and is coming back now, with the limitations of the pandemic only further illustrating Woodhead’s commitment, in his willingness to work around whatever obstacle is in his way.

Now, whereas Woodhead wouldn’t get into exactly where he’s looking to take his game (“I have goals; I’m just not gonna tell anyone those”), Johnson sees potential for not just more runs at the U.S. Open (“Over the next five years, he’ll get through sectionals two, three times maybe”), but has eyes for other big events, too.

“The big goal, the stretch goal, is for him to win the U.S. Mid-Am, that’s the USGA event where it’s 25-and-older,” Johnson said. “The problem with the U.S. Amateur is it’s a college event, and that’s not fair for Danny. Guys there are six months away from being on the PGA Tour. With the US Mid-Am, you have guys that played college golf, but they’re all in real jobs and distanced from those days. So the Mid-Am, if he won it, he’d get in the Masters. And for me, that’s when it becomes fairy tale stuff.

“And does he have the capacity to do it? One-hundred percent. Will he do it? I don’t know. Would it surprise me? Yeah, maybe a little bit, but it wouldn’t shock me.”

But the biggest win for Woodhead is what he’s gotten out of all this, all the way around—a life he can live without any need to look back. And while he’s competitive as anyone now, and was as a football player, he’s always had this sort of different perspective that allowed him to get to this place. It’s obvious in how he looks at all his old football friends who’ve reached out the last couple months as his name returned to the headlines.

“I didn’t win a Super Bowl. I got to play in one,” he said. “If you would tell me that I would get a ring and I would lose those relationships, I’d never take it.”

And it’s just as obvious today, in his everyday life.

“Everyone that thinks life is over when the NFL is over, man, I feel like they’re just completely missing out,” he said. “Ten years in the NFL obviously gave me an incredible head start on this next phase of my life, and trying to do the best I can with what God’s given me, and the relationships I’ve been given. And hopefully any of my friends, whether it be at the club, whether it be who I played with, can say at the least that they enjoyed being around me, and I give them more life than bring them down.

“I think that’s what you want your friends to say, not so much, Man, he’s a really good football player. I want my friends to be able to say, I really enjoy being around him.”

The truth is, for so many of those guys, Woodhead has a lot more than just that to, again, give, and show them—and that’s whether they can swing a golf club or not.

Robert Hanashiro/USA TODAY NETWORK

SIRAGUSA’S OUTSIZED LIFE AND LEGACY

I met Tony Siragusa a few times through his work as a sideline reporter for Fox, so I got to see for myself how real the outsized personality we all saw over the years was.

But I didn’t really know him. Marvin Lewis did. He can confirm what we saw is what he got.

The story of the last time Siragusa and the old coordinator of the first generation of great Ravens defenses saw each other sure shows it. The 2000 group, which stands among the greatest units of all time, was planning to have a reunion two years ago. COVID-19 scuttled it, so tapings in Baltimore for an ESPN documentary on the historic season, held back in May, served that purpose. Lewis arrived late, after midnight, to sit for the filmmakers the next day, and was checking into his hotel when his plans to get some sleep changed.

“Anthony, his son, sees me,” Lewis said Saturday. “They’re going up in the elevator, and they all come right back down and we hang out in the lobby for like an hour. It’s like, ‘Goose, it’s 2 in the morning, man. I gotta go. We gotta get up.’”

Siragusa died at 55 on Wednesday in his native New Jersey, passing away after Toms River Police were called to his house and he received CPR.

The legacy he leaves is as both a football player and as a person.

On the first count, he’ll be remembered as one of the anchors of a defense that started a tradition that, in a lot of ways, mirrors that of the rival Steelers (having been established by Lewis, an ex-Steelers assistant), and lives on more than two decades later. Siragusa was never an All-Pro and, over 12 seasons, seven as a Colt and his final five as a Raven, never played in a Pro Bowl.

But the way he played did help pave the way to those sorts of accolades for a lot of other guys on the star-studded defense around him.

“I think the thing that people say, ‘Well, Goose was big,’” Lewis said. “Yeah, he was big, but he was an athlete, and he was smart. And that’s what made them such a good group up front, because those guys were not only strong but they were so athletic, they were so smart. And he had a lot of adjustments to things up front based on tendencies and formations and everything. And they could handle it all, and so they could really take the game plan and let it unfold on Sundays. And that’s what made those guys so special.

“And he was such a good athlete. He never got knocked off his feet. They had to block him—they had to account for him because they weren’t gonna be able to cut him off or cut him down. He was always able to stay on his feet, which made them have to account for those guys up front. It kept Ray [Lewis] free to go to the football.”

Just as important, Siragusa’s intelligence would show up constantly.

If Lewis would flip a play in the other team’s offense during scout-team work, Siragusa, Lewis says, would be the first to shout over, “They don’t run it like that, Coach!” The ability to think that way, and that critically, wound up helping take the Ravens to another level, because the coaches and players were constantly working together to tweak, adjust and stay ahead of the opponent.

“They knew the opponent inside and out,” Lewis said. “They knew our plan inside and out, and they took it to the field on Sundays and applied it.”

The result, in 2000, was a season in which Baltimore put itself next to groups like the 1985 Bears and the ’70s Steelers among the greatest defenses ever assembled. The Ravens allowed just 165 points and 970 rushing yards that year, both records for a 16-game regular season, while leading the league with 49 takeaways. They then allowed 3, 10, 7 and 10 points in their four-game playoff run to a win in Super Bowl XXXV.

Which brings us to the second count—who Siragusa was a person, and teammate.

Lewis tells the story of how Siragusa would keep bugging him to come over and get a fried turkey from him on Thanksgiving. The coach would tell him he couldn’t because he was busy with family, but Siragusa persisted. “Just come over when you’re done.” So Lewis did, and he saw one of Siragusa’s buddies working the deep fryer in the yard. And more than two decades later, he’d see Siragusa, and the same guys were there.

“He had the same cronies, still hanging around him,” Lewis said. And while it’s funny to think about for Lewis, it also said something about who Siragusa was. “He held people together that way,” he continued. “He was very loyal to them. He took care of them—they took care of him.”

So on one hand, yes, Siragusa was the guy who could always bring the house down, the one who parked his bus in front of Mons Venus during Super Bowl XXXV week after coach Brian Billick specifically told his players to avoid the place when they arrived in Tampa, and the one who once grabbed an ill-fitting leather jacket from a motorcycle cop on the Ravens’ police escort. “Poor motorcycle cop doesn’t have his nice leather coat and Goose is fitting into the size medium leather coat that the guy paid $300 for,” Lewis laughed.

But on the other hand, there was real value in how Siragusa understood the ebbs and flows of a team, and a defense, through a season.

“During the week, he was a pain in my ass,” Lewis said. “And then on Saturday night, all of a sudden, he wanted to know the plan. And he’d be an extension of me on the field. But during the week, he kept everything light and was always messing around with those guys, giving everybody a hard time. No matter what it was, he was in the middle of it giving somebody a hard time about something, but when Sunday came, you couldn’t find a finer teammate.”

Or, Lewis continued, a finer friend. That much was obvious in the charity work he did, and the droves of people who’d come out for his celebrity golf tournament—from Ravens players, to Pitt football alumni like Dan Marino, to the neighbor guys from Jersey. It’d be obvious on wives’ trips to Ravens preseason games against the Jets and Giants, when they’d walk into an Italian restaurant as couples and Siragusa happened to know everyone.

It was there, too, in harder times, and so it was a couple weeks ago when Lewis had his last communication with Siragusa, who’d reached out over text to get Jack Del Rio’s number—Del Rio was linebackers coach for the 2000 team. He wanted to just check in, knowing that Del Rio was dealing with a lot, after his comments about Jan. 6.

“I said, ‘What’re you gonna do? Give him a loan?’” Lewis said. “And he said, ‘Yeah, 300 Italian points.’ And that’s him. I mean, he’s just, no matter what it was, he was there.”

And it breaks Lewis’s heart to know that Siragusa won’t be there for weddings for his three kids, or the birth of grandchildren, or any of the other things a 55-year-old guy has to look forward to in life.

“I know how proud he was of them,” he said. “I will miss him saying, ‘Samantha’s getting married, Anthony’s getting married. And hey, we want you to come.’ Stuff like that. That’s what I’m gonna miss—what he has given everybody else, the joy that he gave everybody else, being able to experience for his family the same joy he gave every one of us.”

Here’s hoping for the best for all of them, at a tremendously sad time.

Ken Blaze/USA TODAY Sports

TEN TAKEAWAYS

The public-relations positioning in the Deshaun Watson case is underway. The NFL has gotten word out there, now on multiple occasions, on what it is seeking: a full-season suspension of Watson. The NFLPA has too, in explaining why it would argue for much lighter discipline, in pointing to precedent set in cases involving owners Daniel Snyder, Robert Kraft and Jerry Jones, where sanctions were either (arguably) light or nonexistent (Pro Football Talk had the report on that one).

And so that leaves the NFL with the ability to say, “We tried,” if Watson gets a lighter penalty, and the NFLPA with the ability to say their case is about consistency, not morality.

One source from the player’s side said their belief is the limited scope of the NFL’s investigation, and the league’s history with these sorts of investigations, should weigh in Watson’s favor. My understanding, along those lines, is that the NFL will present the cases of five women, four of whom the league spoke with, to arbitrator Sue L. Robinson, the former U.S. District Court judge. Twenty-four filed suit, though the league has spoken to women who didn’t sue Watson. Sources say settlement talks collapsed over the league’s insistence on a full-year suspension.

Talks between the league and union on a potential settlement happened two weeks ago, and Robinson scheduled this week’s hearing last week, after the talks broke down.

You’re hearing about all this, too, with an important week ahead. On Tuesday, Robinson will hold her hearing, taking arguments from Watson, the league and the union. At the end of the week, the deadline for pretrial discovery in the four remaining lawsuits will pass. All of which sets up so Robinson’s initial decision could become public just before the Fourth of July weekend.

Of course, that wouldn’t be the end of it. Unless there’s no discipline, which I’d say is highly unlikely (though no one really knows what the arbitrator’s thinking), Robinson’s decision will then go to either commissioner Roger Goodell or his designee, who’ll then hear final appeals and render a ruling. And while Goodell could then impose what the league wanted all along, it might not be great for the league going forward to throw out an arbitrator’s decision in the first high-profile case since the new process went in as part of the 2020 CBA.

Doing so, you could argue, would undermine a process they just negotiated in future cases, and could make it harder to get arbitrators on board to hear them. I’d also say it’s fair to think Robinson might be upset to begin with over how public the arguments being made by both sides have become in recent weeks.

But for now, that just leaves us knowing where the league and union stand. And we might know more later in the week.

I don’t think the Browns have thought much about keeping Baker Mayfield—but maybe they should now. I’ll be clear on this. Holding Mayfield’s rights the last four months, for Cleveland, was never done to create any sort of Watson insurance policy. The Browns wouldn’t have offered to take on much of his salary to facilitate a trade if that was the case. That said, my feeling is the construction of the quarterback room around Watson was done with the thought that he’d miss a percentage of the season, rather than the whole thing.

Making Jacoby Brissett the team’s starting quarterback, with the experienced Josh Dobbs as backup, for six or eight weeks makes sense. The guy has 37 career starts, 14 career wins and a 36:17 TD:INT ratio—as temps go, he’s pretty perfect. But if he’s the quarterback the whole year? We saw where that went for the Colts in 2019, and with a roster full of guys in their primes, it’d make sense for the Browns to want a little more.

Mayfield can give them that. And looking at the landscape, and lack of teams willing to take on even half his $18.85 million number for 2022, you could argue Mayfield’s best shot, and the best team (by far) he could start for this fall would be the one he’s on.

Now, I’ve heard repeatedly that Mayfield’s done with the Browns, and that there’ll be no fence-mending happening. But I’m not sure why, if Watson gets sat down for the whole season, that wouldn’t be the best thing for everyone involved. And I say that fully acknowledging that, if Watson’s only missing a piece of the season, the Browns should redouble their effort to find Mayfield a new home.

I could listen to Rob Gronkowski’s coaches talk about him all day—and hearing Josh McDaniels’s memories of the four-time first-team All-Pro the other day was awesome. The first one I’ll share relates back to the topper for our mailbag last week, where Alabama offensive coordinator Bill O’Brien said Gronkowski made the Patriots’ offense tougher in every game he played, in a first-guy-off-the-bus sort of way.

“I always felt this way,” McDaniels said. “With Tom [Brady], I always knew we had a chance to win. When Tom ran out of the tunnel, I didn’t give a s--- who we were playing, or what game of the year it was, or what odds were stacked against us, I always knew we had a chance to win. With Rob, when he ran out of the tunnel, you always felt like, O.K., we got the baddest guy on the field. It doesn’t matter who you are, you ain’t roughing him up.

“He’s gonna take a defensive end and run him out of bounds. Or he’s gonna pancake a linebacker. Or he’s gonna run a safety over trying to tackle him. Or he’s gonna throw Sergio Brown out of bounds. Like, you just knew, at his position, with the matchups he was going to be faced with, you felt this enormous edge. I’m sure this is what every team that had Shaquille O’Neal felt like when he ran out of the tunnel. Like, nobody’s f---ing with him.”

In turn, that became a part of the Patriots’ identity on offense during the second phase of the New England dynasty.

McDaniels, now in charge in Vegas, was Gronkowski’s coordinator for most of that time, taking over for O’Brien after the 2011 season and remaining through the tight end’s final game as a Patriot (a win in Super Bowl LIII). As such, he has lots to say on No. 87. And with Gronkowski’s retirement this week, it was a good time to catch up with McDaniels on those.

The first point McDaniels wanted to make was that Gronk may have come off as immature, but those who worked with him know there was a whole lot more to him than that. And that’s because, McDaniels says, Gronkowski had an incredible sense of what his team needed, and what he needed, in the moment.

“All that stuff, Rob always knew, When do I lighten it and when do I not?” McDaniels said. “I never, ever, ever had to say, Hey, Robbo, tap in here for a minute and let’s finish this up, and then go ahead and do your thing. When you were coaching, he was as serious and intent on listening to what you were saying as anyone in the room. I think the great misconception about Rob Gronkowski is that he’s immature. He’s not. He’s mature. And so like when you coached Rob, he wasn’t being silly in your meetings.

“Now, I’ve coached guys that don’t know how to do that. You’re telling them all the time, knock it off, or whatever, because they just don’t have the idea of when to do it and when not to do it. Rob never had that problem. When you coached Rob Gronkowski, he sat there with his notepad open, he took notes, he listened intently, he was ready to go. And then when the meeting was over, he went about his life.”

McDaniels’s second point concerned another misconception—that Gronkowski was this rockheaded Ogre-from-Revenge-of-the-Nerds type character. Of course, people should’ve probably known better on that one. The guy scored 10 touchdowns as a rookie in a New England offense that incoming veterans routinely struggle to grasp, and broke the touchdowns record for tight ends in his second year. Still, the idea held that he was just Tarzan out there, when there was a whole lot more to it.

“When I was in Denver, he came and visited with us,” McDaniels said. “I would say just how intelligent he was from a football perspective, his instincts, his savvy, just his ability to learn different things week-to-week, that would’ve been almost impossible to gauge from his film at Arizona, because he was hurt so much, they didn’t do a lot with him. You saw a guy run and catch, he was big, but it was hard to gauge him in terms of how intelligent he was and how much savvy and instincts that he possessed. Like I said, that was pretty special.

“The guy’s very smart.”

And his toughness and intelligence, to put a bow on McDaniels’s thoughts, unlocked Gronk’s physical ability to play so many different spots on the field, which made him a nightmare to deal with. Which is really what separated Gronk from so many other guys (and we covered this part on Wednesday)—when the huddle broke, it was tough for a defense to know exactly how to deal with him.

“So many of the issues on defense were created because he just wasn’t lined up in the same spot the whole game,” McDaniels said. “You had to deal with him as a very traditional tight end, which he was the best that I’ve ever coached, no question. And you also had to deal with him potentially on the move, you had to potentially deal with him split out on the backside of the formation, by himself. And he was able to produce in all those spots.

“There are a lot of guys that get split out but they don’t do anything. Rob could catch touchdowns or create big plays as the widest guy on the field, as the slot receiver, as the traditional tight end, and he could do it with an array of different routes.

“You put a corner on him, he’s too little. You put a linebacker on him, he’s too slow. You put a safety on him, he’s just not agile enough. That’s what made him, his size, his skill, his catch radius was the best I ever coached, him and Randy [Moss]. Anytime the ball was near him, they talk about wingspan in the NBA, Rob’s catch radius was unbelievable, and his hands were an 11 on a scale of 1–10. It was really difficult to stop.”

And that added up to a player who may be unlike any the NFL has ever seen. I did, for what it’s worth, ask McDaniels for his favorite memories. We talked about the 2015 AFC title game, one Gronkowski basically held the Patriots in (they lost to Denver) with the offense around him depleted, and McDaniels pinpointed a single catch from the year before against those same Broncos, in which Gronk reached back with his left hand, in traffic, deep in the red zone, to pluck a ball over Denver safety T.J. Ward.

I found that one on YouTube.

I’d forgotten about it, to be honest, because there’ve been so many great ones since. And then, I thought about it, and you realize that the play came the year after he tore his ACL, when a lot of players are still skittish as they relearn to use a rebuilt knee, and it came over the guy, in Ward, who delivered the hit that blew out the ligament in a game the year before.

So yeah, as McDaniels said, Gronk was one bad dude.

I’m like everyone else. I won’t close the door on Gronk returning. Agent Drew Rosenhaus, over text, said last week that he wouldn’t be surprised to see Gronkowski back in the NFL by the end of the season, and that he could envision a scenario where Brady reaches out to get him back on the Bucs’ roster around, say, the holidays or so. Why would that make sense? I think simple math can explain it.

Gronk made $9.25 million in 2020 and $8 million last year in Tampa. Let’s say the Bucs offered him $8 million to play in ’22. That’s $8 million for five or six months of work and would eat up almost all of the cap space Tampa has left (they’re at about $10 million). And Gronk has set himself up to be good financially for decades to come, so maybe he figures he doesn’t need to endure the toll six months of football would take on his body.

But if Tampa came back with $4 million on Dec. 1? Now we’re talking about a commitment that’d be just over two months, tops, Gronkowski would be fresh physically for the stretch run, and he’d get to see where the Bucs are in the standings before making that decision.

So stay tuned. We might not be done with him.

Next year’s college class looks strong. It’s no secret how much of the NFL saw the 2022 draft—one that had some depth but lacked star power at the top. At this early juncture, it looks like ’23 should make up for it. National Football Scouting, which runs the combine, just distributed its annual summer grades for teams. Here are the top 25 (third-year players hadn’t been included in the past, but now are; and positions listed are NFL projections).

- Jalen Carter, DT, Georgia

- Will Anderson, DE, Alabama

- Tyree Wilson, DE, Texas Tech

- Bryce Young, QB, Alabama

- Bryan Bresee, DE, Clemson

- Michael Mayer, TE, Notre Dame

- Will McDonald, DE, Iowa State

- Kelee Ringo, CB, Georgia

- Isaiah Foskey, DE, Notre Dame

- Jahmyr Gibbs, RB, Alabama

- Brett Johnson, DT, Cal

- Colby Wooden, DE, Auburn

- Derick Hall, DE, Auburn

- Will Levis, QB, Kentucky

- C.J. Stroud, QB, Ohio State

- Joey Porter, CB, Penn State

- Nolan Smith, DE, Georgia

- Cam Brown, CB, Ohio State

- Andre Carter, DE, Army

- Ali Gaye, DE, LSU

- Dawand Jones, OT, Ohio State

- Tyrique Stevenson, CB, Miami

- Kenny McIntosh, RB, Georgia

- Jaxon Smith-Njigba, WR, Ohio State

- Zach Charbonnet, RB, UCLA

The one thing that’s interesting is that the grades don’t exactly match the way the guys are stacked here, with the grades factoring in positional value. In the system that NFS uses, a grade of 7.0 or higher makes a player blue-chip (defined as a truly elite player). Carter graded at 7.5, Anderson at 7.3. Grades of 6.5 and above are red-chip (defined as the kind of player you win because of, rather than win with), and 10 more players (Wilson, Young, Bresee, Mayer, McDonald, Ringo, Foskey, Gibbs, Levis and Stroud) made that cutoff.

Also, Georgia and Ohio State led the way with four players each on this list, while Alabama had three (all in the top 10).

Should be a fun class to follow.

Geoff Burke/USA TODAY Sports

I don’t know that there’s a whole lot else to say on Daniel Snyder. The Commanders’ owner looked terrible again this week in no-showing the House Oversight Committee hearing on the team’s workplace culture, and came off as slimy in a letter to employees pointing the finger at the media for making the team look bad after all the improvements that have come over the last two years—the truth is no one’s pointing the finger at current employees who weren’t there prior to 2020, and an effort to make them a part of this comes off as only to deflect criticism that’s so clearly directed at Snyder himself.

So where does this go next? Snyder’s testimony will be interesting, assuming he’s subpoenaed, as Committee chairwoman Carolyn Maloney promised he would be. And Roger Goodell’s actions in regard to Snyder continue to be interesting.

First, at his Super Bowl press conference, Goodell laid out plainly the process for ousting an owner—it takes 24 votes from the other 31 to get it done. That he’d answer the question so directly, to me, was a remarkable break in character for the commissioner. Second, in his testimony, Goodell repeatedly positioned Snyder’s absence from the team’s day-to-day operations over the last year as a de facto suspension, an idea that Snyder and his henchmen have quietly, and aggressively, been pushing back on since last summer.

That means at two critical points, a commissioner who rarely ever crosses an owner publicly was willing to go on the record first to explain how an owner would be thrown out of the league and second to contradict the narrative an owner’s been trying to push. Without getting too conspiratorial about it, I’d say that’s worth paying attention to. And while I still think the other owners are loathe to actually vote out one of their peers (they don’t want the precedent, or anyone looking through their own trash), it’s not hard to conjure a scenario where, in the months to come, they work to turn up the heat on Snyder.

That said, I’m not really confident there’s a boiling point out there that would get him to sell on his own. We’ll see.

The money part of the Jimmy Garoppolo saga bears watching. The expectation is, and has been, that the 49ers’ quarterback will start throwing again soon. And that could well change everything. The rotator cuff surgery he underwent in March is the main reason the 30-year-old is still a Niner. The problem, for teams that would be interested, is that rehab for this sort of injury, for a quarterback, can be unpredictable. And with just one year left on Garoppolo’s contract, you really would be buying him for right now, with little wiggle room for being patient in letting the shoulder heal.

A real sign that he’s past it changes that dynamic and leaves one more major factor: money.

Garoppolo is due $24.6 million this year. The Niners, I’ve been told repeatedly, are willing to let other teams talk to him about renegotiating the contract—and that’s necessary now, because just two teams (the Browns and Panthers, interestingly) could absorb that lump-sum without any sort of cap maneuvering.

Meanwhile, San Francisco is extremely tight to the cap, with both Nick Bosa and Deebo Samuel needing deals. So when Garoppolo’s healthy, which should be soon, will he be willing to work with another team to lower his number (his salary doesn’t become guaranteed until Week 1, which means the Niners can cut him without penalty before then) to get the chance to start somewhere else? Or will he try to leverage his release, which would likely mean losing money, but getting to pick his destination?

Finding answers to those questions won’t be easy and, accordingly, this situation remains delicate, with camp serving as the next soft deadline to get something done.

I think we should listen to the point Eli Manning was making this week. It was in regard to his ex-Giants teammate, Daniel Jones. But it really could’ve been about any young quarterback.

“By my fifth year, I had been in the same offense the whole time. I knew it, I could coach it up, new guys are coming in, I was speaking the same language as my offensive coordinator and as coach [Tom] Coughlin, and kind of preaching the same stuff,” Manning said on NFL Network at the Manning Passing Academy. “And with [Jones], it’s all new, and it’s learning, and he’s consistently trying to learn and learn and learn, and it just takes some time before it all sinks in.”

Now, consider this …

• Peyton Manning had the same offensive coordinator for his first 11 NFL seasons.

• Brady had the same head coach for his first 20 NFL seasons.

• Aaron Rodgers had the same head coach for his first 10 years as an NFL starter, and played for that head coach for two years before becoming starter.

• Patrick Mahomes has had the same head coach his first five years in the league, and the same coordinator for all four years as starter.

• Josh Allen has had the same head coach for his first four years in the league.

• Joe Burrow has the same head coach, coordinator and position coach his first two years in the league.

Now, to be fair, there’s a bit of a chicken-and-egg argument to all this too—a really good quarterback creates job security for the coaches, through his own play and winning. Still, environment matters. Alex Smith was once the best example of that, with a tumultuous six-year start to the ex-Niner’s career giving way to a mid-career rebirth under Jim Harbaugh. And if you look hard enough at it, Jones, who’s had two head coaches and three play-callers in three years, and will have his third head coach and fourth play-caller this year, is becoming a pretty good example, too.

Here's a rare business-side-of-football take: I think whatever the NFL does with Sunday Ticket will be largely focused on what the viewing experience will look like 10 years from now. DirecTV was great for its time. Back in the ’90s, the idea of having a satellite dish seemed space-aged, and the first real at-home version of one was the perfect way for the NFL to introduce a product that gave fans more access to games than ever before. All these years later? Satellite dishes have gone the way of VCRs.

So I think there’s good reason why Disney, Amazon and Apple are in front of the bidding for Sunday Ticket, and it’s because each has proven to be ahead of the pack on streaming content. That doesn’t mean they will be 15 years from now. But it does mean that for the foreseeable future, those companies probably give the NFL the best chance to reach a younger audience and continue to evolve as technology does.

Now, obviously, money’s going to be a factor in who Sunday Ticket goes to. But I also think the vision each company presents for the future of the product will be, too. And that’s smart, because the NFL knows as well as anyone the importance of continuing to be wherever the audience is going.

My final set of takeaways, before I shut it down for vacation is here. And there are, as usual, 10 of them.

• Condolences to the family and friends of Ravens pass rusher Jaylon Ferguson. Regardless of circumstance, 26 years old is way too young. Obviously, between the news on Siragusa and Ferguson, and given the number of people who’ve worked there for long enough to bridge the eras, it was a very, very tough week for those in the Baltimore organization.

• The health of Colts LB Darius Leonard looms as a pretty big story line for the summer. Leonard had back surgery. And while the expectation is he’ll be ready for Week 1, back problems can linger, and usually make it hard to talk about a rehab timetable in absolutes.

• Really interesting initiative from the NFL, to go into Africa with this sort of purpose.

• I love Chargers quarterback Justin Herbert saying “whatever happens, happens” when it comes to his eligibility for a second contract in early 2023. He, and we, have a pretty good idea what’s going to happen, I’d say.

• Both Micah Parsons (setting a sack “minimum” of 15) and Justin Jefferson (saying he wants to be a Hall of Famer) set high bars for themselves last week. Which is great—both guys have shown the potential they have. They should be ambitious.

• The Tyreek Hill thing shows one of two things. Either we’ve collectively become incredibly sensitive to criticism or we’re all just world-class instigators now. Did anyone really go back and listen to what he said? “[Patrick] Mahomes had the strongest arm, but as far as accuracy-wise, I’m going with Tua [Tagovailoa] all day.” Does it merit asking Mahomes about it? Of course. Does it merit a week of coverage? I … guess so?

• Hill also said Mahomes is “top two, and he’s not two.” And two more things, while we’re here. One, anyone getting death threats over dumb stuff like this is, of course, ridiculous (and it’s probably some knucklehead teenager screwing around). Two, the funniest part of this is the title of Hill’s podcast: “It Needed to Be Said.”

• Good to see the Saints recognizing the place Demario Davis holds on their team, and rewarding him accordingly this week.

• An interesting nugget I picked up: The Rams actually involved Matthew Stafford and Cooper Kupp in the decision to sign Allen Robinson to fill the void left by Odell Beckham Jr. and Robert Woods. To me, it’s smart, and not because players usually know things about other players that coaches and scouts don’t, but also because Stafford and Kupp will be invested in seeing that Robinson succeeds.

• One underrated pivotal player for 2022: Jets tackle Mekhi Becton. If he becomes what he looked like he could be as a rookie, then I think Zach Wilson, and the whole team, could be ready to contend. If concerns on him manifest (and they were real enough for the Jets to seriously consider taking N.C. State’s Ickey Ekwonu No. 4), then New York has itself a tackle problem, and those are tough to manage.

SIX FROM THE SIDELINES

1) Whoever winds up with Kyrie Irving next year will get what they deserve.

2) I love following the NBA draft, and it was through that where I found out about Victor Wembanyama. Go to YouTube and check him out. I think he’s about to make the end of the 2022–23 NBA season very interesting.

3) That Avalanche team is fast, entertaining and impressive, and should be good for a really long time to come. And Nathan McKinnon and Cale Makar are something to see.

4) Big shoutout to MMQB alum, and my buddy, Emily Kaplan for her work on the Stanley Cup Final. I couldn’t be happier to see her rise. Of all the younger people I’ve worked with, I don’t think I know anyone who was more ambitious, and willing to do the work it takes, to reach her goals. It’s great to see it happening.

5) The debate over the LIV Golf tour has been interesting. But honestly, functionally, has it really changed much as far as how most people follow golf? It doesn’t feel like it to me.

6) Regardless of what you think of the Mannings, it’s easy to appreciate the way they handled Arch’s recruitment and commitment to Texas. No top-10 or finalists posts, no jersey shoots splashed on Instagram, no retweeting every nice thing someone says about him. And it’s not that there’s anything wrong with all that stuff—kids should have fun with it, it’s a great accomplishment to be courted that way. I just like how they committed to letting him live life as a kid for as long as they can, and I’d think handling it this way will have some nice benefits in the long run.

BEST OF THE NFL INTERNET

Brady insisting on getting Gronk to Tampa should tell you all you need to know about him as a player.

LOL indeed.

Nothing says “internet report” like someone confusing Trevor Lawrence’s actual signing bonus for his crypto endorsement signing bonus.

Pacman’s had his issues, but it’s really great what he’s doing for his late teammate’s kid. And it sure looks like Chris Henry Jr. can ball (Ohio State offered him earlier this month, and I can tell you that program doesn’t just throw offers around, especially at receiver).

Mike Tomlin’s so good at illustrating why coaching an NFL team is so much more than what goes on a play sheet.

Just a great picture that captures Siragusa, all the way through.

I’m convinced Eli could teach a class on social media. So much so that I wonder if he’s got some consultant running that account.

The pause before … “yeah” … on the Allen video is fantastic. (And Taylor Lewan and Will Compton are doing a great job with that podcast.)

… Although this took the edge off a little.

That’s what’s great about the NBA draft—the mystery. That guy over there? Is that hat indicative of who he’s going to play for or … not? Let’s go to Adrian Wojnarowski for more.

I don’t even know why this is funny anymore. It just is.

WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW

I’m on vacation! Over the next three weeks, you’ll get three outstanding guest columnists who we’re excited to roll out for you. And I’ll be back on July 25, fresh off a concert at Wrigley that weekend, and raring (hopefully) to go on my training camp trip.

But until then, keep locked at the site. We’ll have plenty of coverage on Watson, Snyder and anything else that pops through the (normally) quiet time on the NFL calendar.

And I’ll see you on the other side.