Greenpeace accuses ECan of throwing an ex-staffer 'under a bus'. David Williams reports

It took more than two decades for Canterbury’s regional council to notice a water consent for the Wilberforce River wasn’t being adequately monitored.

The scientist who discovered the problem, Wilco Terink, went on to find evidence the maximum discharge rate from the river was being exceeded.

The regional council, known as ECan, hasn’t published his research – although Newsroom published details from a leaked version last year – and Terink left the organisation in frustration.

Now, ECan is distancing itself from Terink’s report, and is publicly backing NZX-listed Trustpower that owns the Wilberforce consent.

Regional leader of compliance delivery James Tricker says there have been very few discharge exceedances since an improved metering system was installed and it is “generally satisfied” with compliance.

“The ‘Wilco Terink report’ you refer to is not an ECan report and we will not be commenting on unsubstantiated information,” Tricker says in an emailed statement.

“As previously stated, we are working to finalise a report into the Rakaia water balance model, and when it is ready to publish we will gladly share it with you.”

Greenpeace Aotearoa says disowning the report is a “shocker” and the council is throwing its former staff member “under a bus”. “It’s evidence that ECan is failing to take its responsibilities seriously,” says Christine Rose, the environmental lobby group’s senior agricultural campaigner.

Trustpower’s general manager of generation Stephen Fraser says the company operates its assets in line with consent conditions and cooperates fully with regulators to ensure compliance.

The claims in the now disowned report prompted the Environmental Defence Society to commission a legal analysis and issue a legal threat. Last month, EDS and Fish & Game met ECan, after which an agreement was reached to seek a joint Environment Court declaration.

Terink’s project, started in April 2018, was prompted, in part at least, by concerns over lower flows on the Rakaia River.

Lake Coleridge is a big factor in the Rakaia’s flows – and not just because of Trustpower’s hydroelectric power scheme, first commissioned in 1914. After a 2013 amendment to the river’s national water conservation order, the company was able to store water in the lake and release it along the Rakaia for irrigators, like Central Plains Water, to take further downstream.

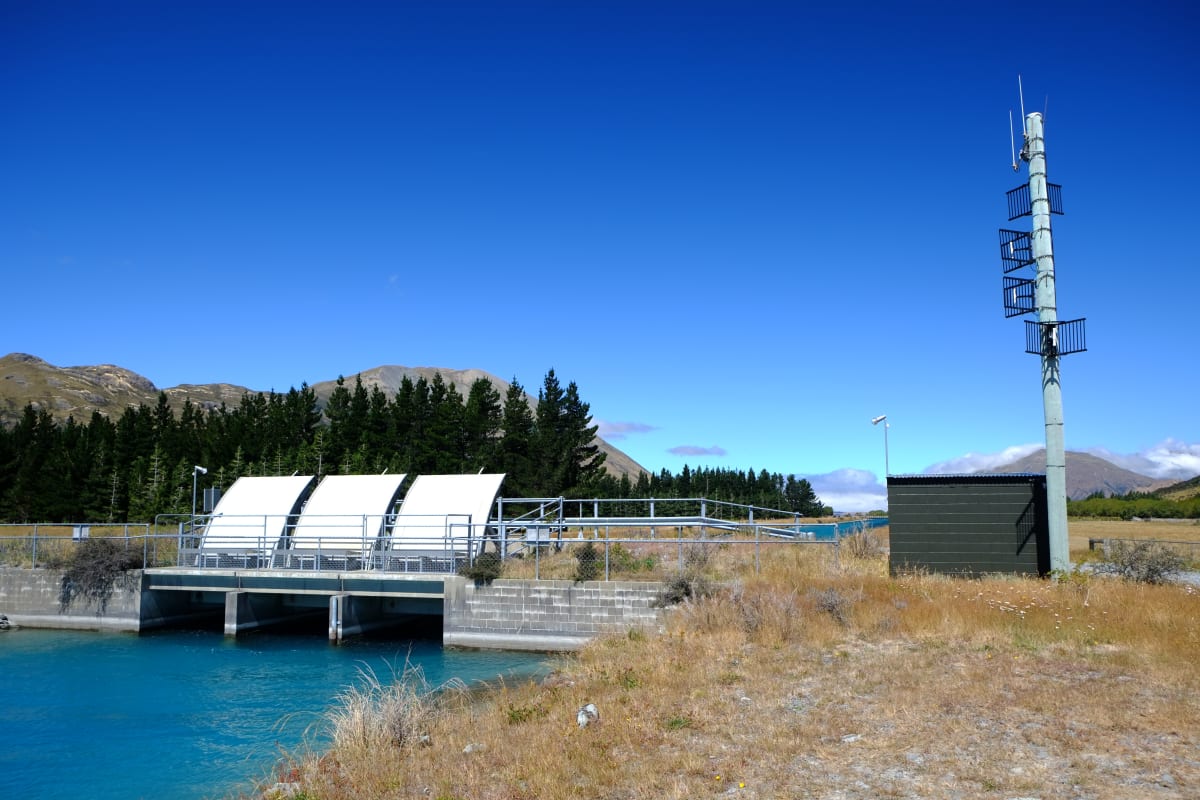

Diversion takes and discharges from the Wilberforce River have operated in one form or another since 1977.

A 1996 consent, issued to Electricity Corporation of New Zealand, states water discharged from the Wilberforce canal, bound for the hydroelectric power station at Lake Coleridge, has a maximum rate of 30 cubic metres a second (cumecs).

If flows in the Wilberforce canal were above 30 cumecs – which, Terink found, they often were – the excess was meant to flow over a spillway before entering the Oakden canal.

But it was difficult to tell if that was happening.

Another complication arises because the Oakden’s discharge rate into Lake Coleridge is 50 cumecs, as it also takes excess water from the Harper River and its tributaries.

What that means is when the diversion into the Wilberforce canal and the discharge into the Oakden canal were running at above 30 cumecs it wasn’t clear how much water into the Oakden came from the Wilberforce.

In other words, it wasn’t clear if the Wilberforce canal’s maximum discharge rate was being met.

Terink’s analysis took him to the skies. The senior hydrological scientist and data analyst used imagery from a European Space Agency satellite to check consent compliance.

He checked three dates in 2016, 2017, and 2018 – when flows in the Wilberforce and Oakden canals were more than 30 cumecs – to see if water was flowing over the Oakden spillway.

On May 18, 2016, no water was detected flowing over the spillway which, the report states, “clearly demonstrates a breach” of Trustpower’s latest consent. No such breaches were shown on the dates in 2017 and 2018.

However, Terink’s report highlights 16 other dates, between 2005 and 2017, on which Wilberforce and Oakden canal flows were above 30 cumecs.

The report’s executive summary – excised from a sanitised version sent to fishing groups last year – highlighted diversions from the Wilberforce River into the canal, after the 2013 amendment of the water conservation order, had been substantially higher.

The report noted: “The quality and availability of water metering data for resource consents in the Rakaia catchment is poor, making consent compliance very difficult if not impossible to determine.”

“Since this more accurate monitoring has been put in place very few exceedances have occurred.” – James Tricker

ECan’s Tricker, the regional leader of compliance delivery, confirms that problems monitoring the Wilberforce Canal discharge only came to light when Terink started analysing Trustpower’s data in more detail.

The council doesn’t have real-time access to flow meters. Under current rules, Trustpower is required to submit daily abstraction data just once a year: by July 31. (From September, however, new regulations require Trustpower to provide 15-minute abstraction data once a day.)

Before 2019, Trustpower only provided ECan with data from the Oakden canal – “which they considered to be sufficient for us to determine compliance with the Wilberforce take and discharge consents”, Tricker said.

However, once Terink highlighted the situation, ECan advised the company it had to provide Wilberforce canal abstraction data from its already-installed measuring system. This information was required, Tricker says, because it would “determine compliance with the Wilberforce consents, based on our interpretation”. (However, comparing data from the two canals doesn’t determine how much water is flowing over the Oakden spillway.)

“Since this more accurate monitoring has been put in place very few exceedances have occurred, and we are generally satisfied with the rate of compliance with the 30 cumec limit.”

Measuring diversions and discharges was being affected by high lake levels, causing water to back up the Oakden canal, ECan said. The issue was resolved by installing more sophisticated measurement equipment.

It’s worth painting this picture again.

Until 2019 – 20 years after Trustpower bought the Lake Coleridge hydro scheme from ECNZ – ECan’s “monitoring” of the Wilberforce diversion relied on data submitted annually by the company operating the scheme, from which it was difficult to decipher how much water was being discharged. And even though Trustpower measured flows in the Wilberforce canal, it didn’t provide that data – and ECan didn’t think to ask for it.

Fraser, the Trustpower general manager of generation, says it uses a combination of in-river gravel bunds and spillways at the Wilberforce and Oakden canal intakes to manage flows.

“This, combined with control gates at the Oakden Canal, provides an effective method for ensuring the diversion of water into Lake Coleridge from the Wilberforce River is compliant with our consent conditions.”

Non-compliance events are rare, he says, adding “we seek to inform regulators of them promptly, typically within 24 hours”.

ECan’s Tricker explains the Wilberforce intake is “manually controlled”, requiring extensive river-works to increase, reduce or cease abstraction.

“During times of flooding, health and safety constrains what work can be undertaken, meaning temporary exceedances of the 30 cumecs Wilberforce canal limit can occur.”

Since 2019, these exceedances – at a maximum of 3.7 cumecs – have occurred over a total of 3.41 days.

Excess water is designed to be returned to the Wilberforce River via the Oakden Canal spillover and the Harper River. Tricker says: “We ensure that this occurs through looking at the Oakden canal abstraction data.”

A question might be, did this always happen prior to 2019 when Trustpower was only supplying the Oakden canal data? Newsroom put to Tricker the Terink report proved this wasn’t the case.

That’s when he disowned the report as “not an ECan report”, calling its contents “unsubstantiated information”.

“Environment Canterbury considers that these consents allow Trustpower to take a maximum of 30 cumecs from the Wilberforce,” Tricker says.

“Trustpower have agreed to our interpretation but, as explained … are unable to meet this limit at all times due to the Wilberforce gate being manually controlled.

“Environment Canterbury continues to work with Trustpower to make sure they comply.”

Rose, of Greenpeace, isn’t reassured. She thinks ECan is hiding behind technicalities to avoid responsibility, in a way that diminishes transparency and public confidence.

She says there appears to be a culture within the regional council of putting the interests of profits before public goods and the environment – including, in this case, a high-value river managed by a water conservation order.

“It’s quite worrying, given the extent of intensive dairying, the contamination of groundwater and aquifers and rivers, and what that means for the environment generally.”

She notes the Government’s recent freshwater reforms will require regulators like regional councils to put the interests of rivers first.

“We need to have confidence that the regulators are doing an independent job, and in a timely, accountable, and transparent manner. And it’s clearly not the case with ECan.

Also, if there are other consents not being monitored properly, one would hope it doesn’t take another two decades to come to light.