The word “narcissism” is often associated with selfies, posting content that boasts one’s achievements, or other forms of showing off.

In Indonesia, the world’s largest Muslim-majority country, “showing off” can also take the form of religious expression.

This was on display in the discrimination and attacks against heterodox Islamic groups such as the Shia community in East Java and South Sulawesi, and also the Ahmadiyya community in Banten.

These interdenominational conflicts involved younger and older adults, as a form of “collective religious narcissism”. This psychological tendency can span a community and is based on a certain religious bond.

My research has attempted to understand this phenomenon, and investigate what it looks like in practice, by looking at four Instagram and Facebook pages of youth Muslim groups in Indonesia.

Collective narcissism

In psychology, the concept of narcissism is taken from Greek mythology. The Thespian hunter Narcissus is said to have fallen in love with his own reflection in a pool of water. His name was then adopted as a psychological term for someone exhibiting tendencies of extreme self-admiration.

Narcissism was then acknowledged in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Its most extreme form entails a number of symptoms, including: intense fixation on one’s self; feelings of superiority; a lack of empathy; and tendencies to exploit others.

According to psychology researchers Kevin S. Carlson and Joshua Grubbs, narcissism is most prevalent among young people. Grubb’s research found people in the 18-25 age group are often more narcissistic than their older peers.

Social psychologist Agnieszka Golec de Zavala also posited that narcissism, often starting at the individual level, can develop into a group symptom. For instance, narcissism can manifest in a range of collective phenomena, including ethnocentrism, hyper-nationalism, and religious extremism.

So how do these forms of collective narcissism show themselves among religious youths in Indonesia?

Indonesian youth, in-group logic, and religious superiority

My research attempts to investigate this by looking at a number of accounts on Instagram and Facebook.

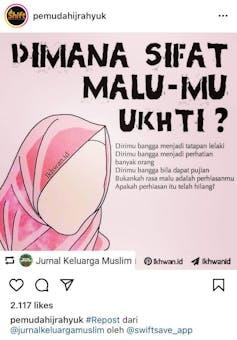

These include the youth movements of Indonesia’s two largest Muslim majority organisations, Nahdlatul Ulama (@generasi_muda_nu_official) and Muhammadiyah (@pp.pemudamuhammadiyah). I also studied posts by @pemudahijrahyuk (a conservative Islamic youth movement) and Indonesia Tanpa Pacaran/ITP (a youth-led movement advocating for Muslims to reject modern dating).

Although my initial study was conducted in 2019, I argue these groups’ posts in 2022 still follow a similar pattern of advocacy and self-expression.

The youth wings of Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) and Muhammadiyah, for instance, show religious expressions that focus on in-group pride. Muhammadiyah projects messages of self-confidence, potentially as an attempt to bolster a sense of loyalty within the organisation.

The young cadres of NU, similar to their Muhammadiyah counterparts, also proactively express themselves in the digital space.

They often share posts containing messages of self-belonging, pride and greatness. In a 2019 post, an NU regional leader was quoted saying that his organisation’s members are on the “right path to religious truth”.

However, they sometimes upload responses that can be considered aggressive or offensive toward those that do not share their views.

Earlier last month, for instance, the account uploaded a post supporting Saudi Arabia’s call to behead Muslims that advocate for the establishment of Islamic states or caliphates, and urging Indonesia to do the same.

While the ‘collective narcissism’ exhibited by the two Muslim organisations above mostly focus on their sense of pride, posts by Pemuda Hijrah (roughly translated as ‘Youth Returning to Islam’) and Indonesia Tanpa Pacaran (roughly translated as ‘Indonesia Without Dating’) contain strong sentiments of superiority.

Posts by Pemuda Hijrah actively invite Muslims to adopt Islamic puritanism – a form of the religion that more closely conforms to its original teachings and social context in the 7th century.

The views of these youth-led movements are often viewed as conservative, although their social media posts sometimes also reference popular culture, from TikTok posts to Korean dramas.

In a 2019 post, for instance, the group expresses concern and attacks other Muslim women who wear clothes they regard as provocative or revealing the “awrah” — men’s and women’s body parts that may be considered intimate in Islam.

Meanwhile, Indonesia Tanpa Pacaran represents a group that militantly rejects modern dating in Indonesia. In numerous posts, such as one uploaded last July, the group vilifies other Muslim women who participate in that culture.

From these social media accounts, we see examples of how Indonesia’s youth Muslim groups express various forms of collective religious narcissism.

Some of them can be considered “positive”, in line with French psychoanalyst Andre Green’s argument, as being able to boost individuals’ self-esteem and drive for group activity.

On the other hand, others can be considered “negative” and exhibit narcissism that focus on feelings of religious superiority at the expense of those who do not share their views.

Some of those posts, for instance, express messages that tend to devalue other Muslims and push an “us versus them” narrative that could potentially cause discrimination and oppression.

Young Indonesians need to be more aware and empathetic

Based on the above examples, we still see some individuals and groups in Indonesia that champion certain labels of Islamic tradition in a way that tends to be hostile to others, fueled by their in-group logic.

These expressions can push individuals or communities to legitimise violent behaviour in the name of group loyalty.

Young people in Indonesia need to be aware of these social and psychological tendencies – particularly those that strive to exert social dominance over other minority groups.

Training ourselves and the groups we’re involved in to be more empathetic, is now more important than ever to preserve harmony within our society, and in turn, suppress potential points of conflict between religious groups.

Muhammad Naufal Waliyuddin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.