China’s National Bureau of Statistics has confirmed what researchers such as myself have long suspected – that 2022 was the year China’s population turned down, the first time that has happened since the great famine brought on by Chinese leader Mao Zedong in 1959-1961.

Unlike the famine, whose effects were temporary, and followed by steady population growth, this downturn will be long-lasting, even if it is followed by a temporary rebound in births, bringing forward the day the world’s population peaks and starts to shrink.

The National Bureau of Statistics reported on Tuesday that China’s population fell to 1.412 billion in 2022 from 1.413 billion in 2021, a decrease of 850,000.

The Bureau reported 9.56 million births in 2022, down from 10.62 million in 2021. The number of births per thousand people slid from 7.52 to 6.77.

China’s total fertility rate, the average number of children born to a woman over her lifetime, was fairly flat at an average about 1.66 between 1991 and 2017 under the influence of China’s one-child policy, but then fell to 1.28 in 2020 and 1.15 in 2021.

The 2021 rate of 1.15 is well below the replacement rate of 2.1 generally thought necessary to sustain a population, also well below the US and Australian rates of 1.7 and 1.6, and even below ageing Japan’s unusually low rate of 1.3.

Calculations from Professor Wei Chen at the Renmin University of China, based on the data released by the National Bureau of Statistics data on Tuesday, put the 2022 fertility rate at just 1.08.

Births declining even before COVID

In part, the slide is because three years of strict COVID restrictions reduced both the marriage rate and the willingness of young families to have children.

But mainly the slide is because, even before the restrictions, Chinese women were becoming reluctant to have children and resistant to incentives to get them to have more introduced after the end of the one-child policy in 2016.

One theory is that the one-child policy got them used to small families. Other theories involve the rising cost of living and the increasing marriage age, which delays births and dampens the desire to have children.

In addition, the one-child policy left China with fewer women of child-bearing age than might be expected. Sex-selection by couples limited to having only one child lifted the ratio of boys to girls to one of the highest in the world.

Deaths growing, even before COVID

The number of deaths, which had roughly equalled the number of births in 2021 at 10.14 million, climbed to 10.41 million in 2022 under the continued influence of population ageing and COVID restrictions.

Importantly, the official death estimate for 2022 was based on data collected in November. That means it doesn’t take into account the jump in deaths in December when COVID restrictions were relaxed.

China might well experience a rebound in births in the next few years as a result of looser COVID restrictions, an easing of the pandemic and enhanced incentives to have more children.

But any such rebound is likely to be only temporary.

When the total fertility rate is as low as China’s has been for a long time, without substantial inward migration, a decline in population becomes inevitable.

Population prospects bleak

Last year the United Nations brought forward its estimate of when China’s population would peak by eight years from 2031 to 2023.

My calculations suggest that if China was to quickly lift its total fertility rate back to the replacement rate of 2.1 and keep it there, it would take 40 or more years before China’s population began to consistently grow again.

And bringing fertility back to 2.1 is most unlikely. Evidence from European countries, which were the first to experience fertility declines and ageing, shows that once fertility falls below replacement it is very hard to return it to 2.1.

If China was instead merely able to lift fertility to 1.3 by 2033, then gradually to 1.49 by the end of this century as the United Nations assumed last year, China’s population would continue to decline indefinitely. That central UN projection has China’s population roughly halving to 766.67 million by the end of the century.

Just as likely is that China’s total fertility rate will slip even lower. The Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences experts a drop to 1.1, pushing China’s population down to 587 million in 2100.

A more severe scenario, put forward by the United Nations as its low case, is a drop in total fertility to around 0.8, giving China a population of only 488 million by the end of the century, about one third of its present level.

Such a drop is possible. South Korea’s total fertility rate fell to 0.81 in 2021.

China’s population drives the globe’s population

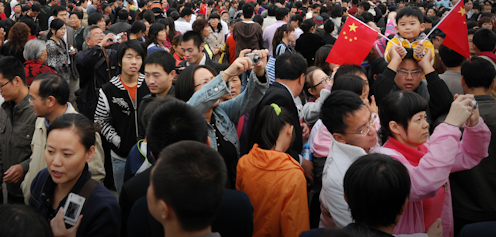

China has been the world’s biggest nation, accounting for more than one sixth of global population. This means that even as it shrinks, how fast it shrinks has implications for when the globe’s population starts to shrink.

In 2022 the United Nations brought forward its estimate of when the world’s population will peak by 20 years to 2086. The Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences forecasts for China would mean an earlier peak, in 2084.

India is likely to have overtaken China as the world’s biggest nation in 2022. The UN expects it to have 1.7 billion people to China’s 1.4 billion in 2050.

Forecasting when and if the global population will shrink is extraordinarily difficult, but what has happened in China is likely to have brought that day closer.

Xiujian Peng works for/consults to/owns shares in the Centre of Policy Studies, Victoria University. She receives funding from Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences from 2017 to 2019.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.