Yelena Monroy was 3 years old when she was imprisoned for more than a year along with her younger sister and her mother, a socialist activist targeted by the regime of Gen. Augusto Pinochet after he came to power in Chile in a military coup in September 1973.

“We were scared, we were crying,” recalled Monroy, now a 53-year-old commercial engineer and one of more than 1,000 children and adolescents who were detained in the name of fighting communism and leftist guerrillas during Chile's military dictatorship from 1973 to 1990.

When Pinochet installed himself as leader, the age of majority in Chile was set at 21 years. But being a minor was no protection from the dictatorship's crackdown. Children were detained, tortured, killed, and even used as decoys to apprehend their parents.

The trauma of that period has made many of the young victims of the military regime reluctant to speak out, and the process of prosecuting that era's crimes and making reparations generally has made no distinction among victims based on age. So, the child victims of the Pinochet era have not had much visibility, though minors represent nearly 10% of the deaths attributed to the regime.

“We don’t classify them by age, because they all suffered,” Gaby Rivera, president of Chile's Association of Relatives of the Detained-Disappeared, told The Associated Press.

However, the National Commission on Political Imprisonment and Torture figures show that the Pinochet regime detained 1,132 minors under the age of 18. Of these 88 were under 13 and 102 were arrested along with their parents — or were born in prison.

Some 307 children under the age of 18 were killed during that period, according to human rights groups' reviews of documentation from the National Truth and Reconciliation Commission. About 3,200 people overall were killed during the dictatorship, or went missing and are believed dead.

Chile's National Stadium, in the country's capital, became the largest detention center of the military government. That is where they arrested — and beat — Roberto Vásquez Llantén, when he was 17, for being an active militant of the Revolutionary Left Movement.

He had been in hiding since the start of the coup, but was arrested on Jan. 15, 1974. Vásquez Llantén, who is 67 today, spent a year in the Chacabuco Prison Camp in the Atacama desert along with 16 other minors. There was no electricity or hot water, he recalled. There were antipersonnel mines outside the barbed-wire to keep prisoners in line, while guards kept watch from towers.

If minors had political significance, they were detained just like adults. But they also were used as lures to trap and detain their parents.

The Fernández Montenegro sisters were imprisoned in February 1974 when they were teenagers.

Viviana, 14, and Morelia, 17, were accused of being guerrillas in the Chilean port of Valparaíso where they lived, some 120 kilometers (75 miles) northwest of the capital. Their mother was arrested and released after 24 hours. The whole family, with the exception of the father, were active communists.

The sisters were first held together in the Silva Palma Navy Barracks, on one of the many inhabited hills of Valparaíso.

“I was in a cell, wearing a hoodie, while some guys put electricity cables on my fingers, yelling and screaming profanities and threats," demanding to know where the weapons were, Viviana Fernández recounted.

“The only thing I did was cry and cry ... I felt very afraid, very afraid," she said.

Fernández, who is 64 today, and Yelena Monroy are members of the Association of Former Minors Victims of Political Imprisonment and Torture, created nine years ago in part to raise awareness about the fate of children and adolescents under the dictatorship.

Fernández, who is the spokesperson, says the organization has about 100 members, but she thinks there are many more, and that many are still afraid to talk about what happened to them during those years.

Many other minors of that time did not survive to tell their story.

José Gregorio Saavedra González, a militant of the Revolutionary Left Movement, was executed at the age of 18 by soldiers in Calama, in the north of the country, together with 25 other political prisoners on Oct. 19, 1973. He was one of the disappeared who years later were located — and identified.

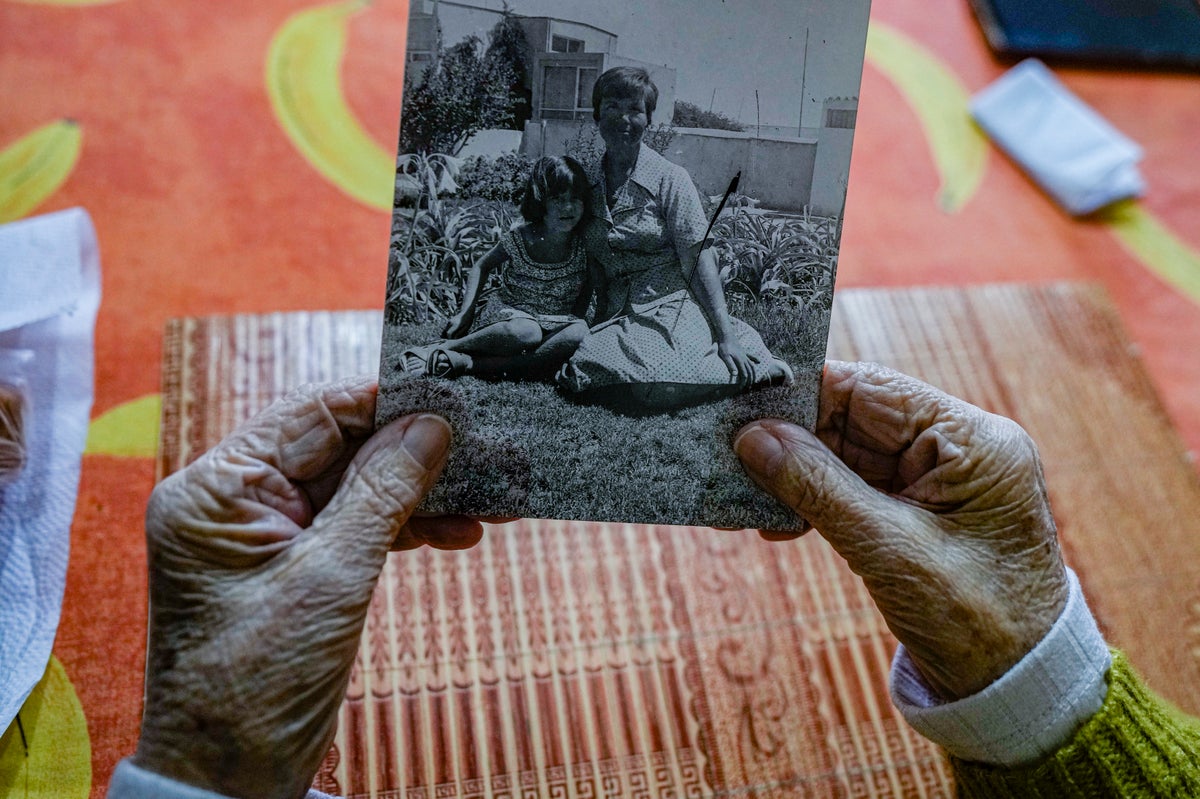

“They gave us a little bit of a finger in a small box, and a little bit of what I imagine was a small tooth,” recalls his sister, Ángela Saavedra, who is 81.

Monroy and Fernández fault the Chilean government for not fully acknowledging past violations of children's human rights.

“We have been totally forgotten by the state, it is very much in debt,” Fernández said.