In August 2022, Republican Gov. Greg Abbott of Texas staged a political publicity stunt by spending nearly $13 million in public money to bus migrants, who had crossed that state’s sprawling Mexican border seeking asylum, to northern Democratic cities. These refugee men, women and children have unexpectedly arrived in Chicago with little more than the clothing on their backs.

As a result of this unnecessary and heartless act of cruelty, these political pawns, through no fault of their own, have created a humanitarian crisis in our city. By all accounts, Abbott and other like-minded Republican governors intend to continue this practice so closely akin (if not identical) to human trafficking.

The citizens of Chicago have shouldered the responsibility of caring for thousands of men, women, and children who have no resources of their own. In a letter to Abbott, former Mayor Lori Lightfoot wrote:

“Nearly all the migrants have been in dire need of food, water, and clothing and many needed extensive medical care. Some of the individuals you placed on buses were women in active labor, and some were victims of sexual assault. None of these urgent needs were addressed in Texas. Instead, these individuals and families were packed onto buses and shipped across the country like freight without regard to their personal circumstances …”

Assimilating migrants is certainly nothing new for the “City of the Big Shoulders.” Looking back through our rich history, we can find a ready-made blueprint for addressing this newest immigration challenge.

In 1887, Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr, prominent American social reformers and activists, traveled to London where they visited Toynbee Hall, a settlement house in that city’s East End.

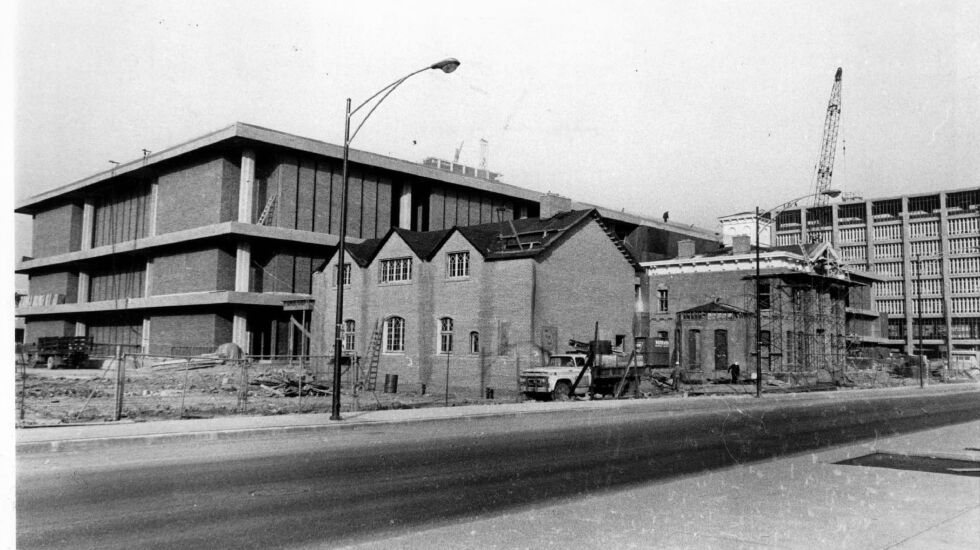

Inspired by the work of Toynbee Hall and its efforts to address the social issues caused by urban poverty, Addams and Starr decided to establish a similar institution in Chicago. They returned to Chicago to establish Hull House, which opened its doors on Sept. 18, 1889, and became one of the most influential settlement houses in the United States.

Helping migrants — and those in poverty already here

Toynbee Hall still exists today, but sadly, the Hull House Association closed its last facility in January 2012. Lessons from the mistakes and missteps that led to its demise have been well-documented and are readily available.

Despite the failings of Hull House’s past leadership, there are practical advantages to resurrecting the Jane Addams settlement house movement, not only in solving our immediate immigrant crisis but also in addressing the concern and resentment of impoverished communities of color, who feel that the needs of the new migrants are taking precedence while their own needs are being ignored.

This became apparent during the recent City Council debate about granting additional funding to help asylum-seekers.

Additionally, such an organization can act as an incubation and umbrella agency as well as a clearinghouse for funding and supporting all community members who need settlement social services, not just immigrants.

A settlement house agency would provide a platform for funding lobbying to advance immigration reform legislation, as well as addressing homelessness and other pressing social issues.

Perhaps the MacArthur Foundation could provide grant money for organizing a settlement house revival. The Chicago Community Trust, The Joyce Foundation, the McCormick Foundation and others might create a 21st century “Settlement Fund” to include decade-long funding for a renewed Hull House coupled with other immigration and neighborhood transformation support.

The University of Illinois Chicago, where the original Hull House is now a museum, is home to the Jane Addams School of Social Work, which could provide some funding and student volunteers.

Perhaps the Union League Club, the Standard Club, the University Club, the Civic Federation and similar organizations would provide the forum and impetus for private funding.

If we all pull together, Chicago could revive the Hull House settlement movement.

The Spanish-American philosopher George Santayana wrote “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” Chicago’s history has provided us with an exemplary template for supporting those who are in need, regardless of whether they are recent arrivals or longtime residents.

Stan Hollenbeck is a former director of the Chicago City Council’s Legislative Reference Bureau and was an associate board member of the Jane Addams Hull House Association in the late 1960s.

Send letters to letters@suntimes.com

The views and opinions expressed by contributors are their own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Chicago Sun-Times or any of its affiliates.