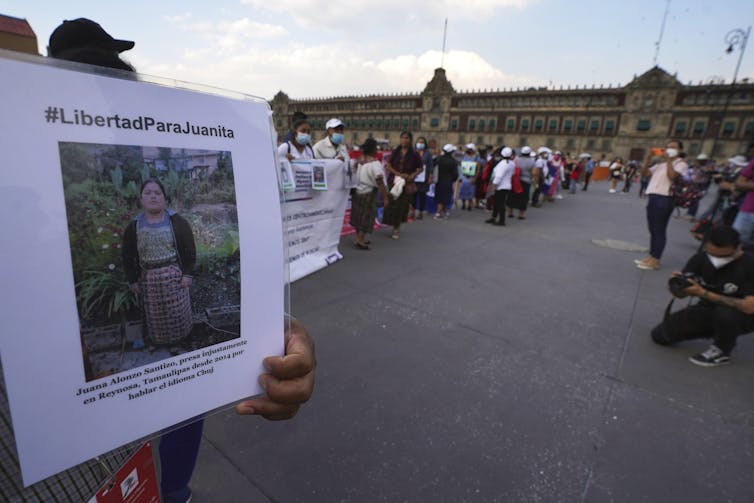

On Mexican Mother’s Day on May 10, 2022, Central American and Mexican mothers searching for their disappeared children marched through the streets of Mexico City.

They demanded answers from President Andrés Manuel López Obrador and are seeking justice for their loved ones who suffer violence across the vertical border, a reference to how the U.S.-Mexico border has been extended across all of Mexico territory to block Central American migrants.

Beyond their aim to find or at least learn what happened to their children, they grieve and collectively contest the brutalities that migrants in search of safety and protection are experiencing in Mexico today.

Migrants disappearing

The disappearances of Central American migrants in Mexico quadrupled in 2021. This is a direct outcome of Mexico’s enhanced policing of unwanted migrant flows and directly related to the selective, racist outsourcing migration policies by the United States and Canada.

Read more: The role of Canadian mining in the plight of Central American migrants

In recent years, I have witnessed the outcomes of a staggering number of kidnappings, arbitrary detentions, incarcerations and gendered violence in the region. Women’s rights and activist groups in Mexico stress that the government is both overseeing and actively concealing the situation.

They argue that exceptionally high rates of both femicide and impunity for its perpetrators, along with the efforts to thwart feminist organizations, are part of Mexico’s historical patriarchy and structural racial state violence.

Read more: In Mexico, how erasing Black history fuels anti-Black racism

The National Centre for Human Identification was recently established to improve and centralize the search for missing people. The centre has been celebrated, though the fact that it was established without a budget, as well as the role that the state itself plays in many of the disappearances, are disregarded.

Data collected by the National Search Commission recently reported that 100,000 persons are officially listed as missing in Mexico. Mothers, and groups supporting their search, believe the actual number — which is growing daily — is much higher while efforts to find missing people are largely inadequate.

The latest caravan of mothers

In May 2022, I accompanied the XVI Caravan of Mothers from Central America through four Mexican states as they called attention to and demanded action for their disappeared children.

The final march in Mexico City ended a long list of political actions carried out in multiple cities by this year’s caravan, which was co-organized by el Movimiento Migrante Mesoamericano, Puentes de Esperanza and national search committees from Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala.

Some of the mothers have participated in the caravan since it was first established in 2005. Others, whose daughters and sons have disappeared in the last couple of years, joined for the first time as the COVID-19 pandemic and related travel restrictions prevented them from initiating their search earlier.

Carrying portraits of their missing children, more than 60 mothers and other family members publicly displayed both their grief and their political grievances. In the words of Mayan community feminist Lorena Cabnal, to “acuerpar” involves taking personal and collective action via the gathering of mothers, outraged by the injustices experienced by their children, and generating political pressure. The closeness and collective indignation results in revitalization and new strength.

As one of the mothers told me:

This shared fight of grievance and hope momentarily displaces my pain. It gives me strength to continue the search and to denounce the systemic violence towards migrants.

The power of mothers

Employing maternalism in political protests isn’t unique, but something seen in Latin America and other parts of the world throughout history. This includes mothers searching for their disappeared migrant children in Tunisia, African-American mothers calling out police brutality that has result in the murders of their children in the U.S. and families demanding answers about missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls in Canada.

Read more: MMIWG: The spirit of grassroots justice lives at the heart of the struggle

What is special about the Central American caravan of mothers, however, is how it is also an important space for collective self-care across borders. That concept involves self-defence and political agency employed by those practising it.

This makes the caravan a space where, along with grieving, both personal and collective care are cultivated among the mothers who share the pain and indignation of not knowing if their children are dead or alive, and if still living, what they’re enduring.

Two disappeared people, in fact, were found and reunited with their families during this year’s caravan. Both had been arbitrarily incarcerated for years in Coatzacoalcos, in southeastern Mexico, and in Reynosa, near the Mexico-U.S. border.

Collective self-care creates relationships and understanding that are not commonly seen elsewhere, according to Kata Lopez, a psychosocial worker from Guatemala accompanying the searching mothers.

The caravan that takes place two weeks every year receives a lot of media attention, she says, while all the work that is done throughout the rest of the year is less known.

Insights from three mothers

I spoke often with the three co-ordinators of the national search committees — Eva from Honduras, Anita from El Salvador and Maria from Guatemala. Their search, together with other mothers and family members, is constant.

Every day there is something new happening, my phone never stops ringing, says Eva. And the more we work, the more cases of disappeared persons are reported to us.

This is the “other, less known pandemic,” adds Maria.

Anita points out that the world is only aware of a small fraction of Central American migrants who disappear in Mexico.

The three mothers agree that their fight is difficult, but that they cannot and do not want to leave #HastaEncontrarles (until we find them in English), until their children are found.

It’s a cause that should affect us all, they say, since it illustrates what so many people are experiencing as they navigate a violent and unjust world.

Linn Biorklund is affiliated with York University Centre for Refugee Studies and Centre for Research on Latin America and the Caribbean. She receives funding from Canada's Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.