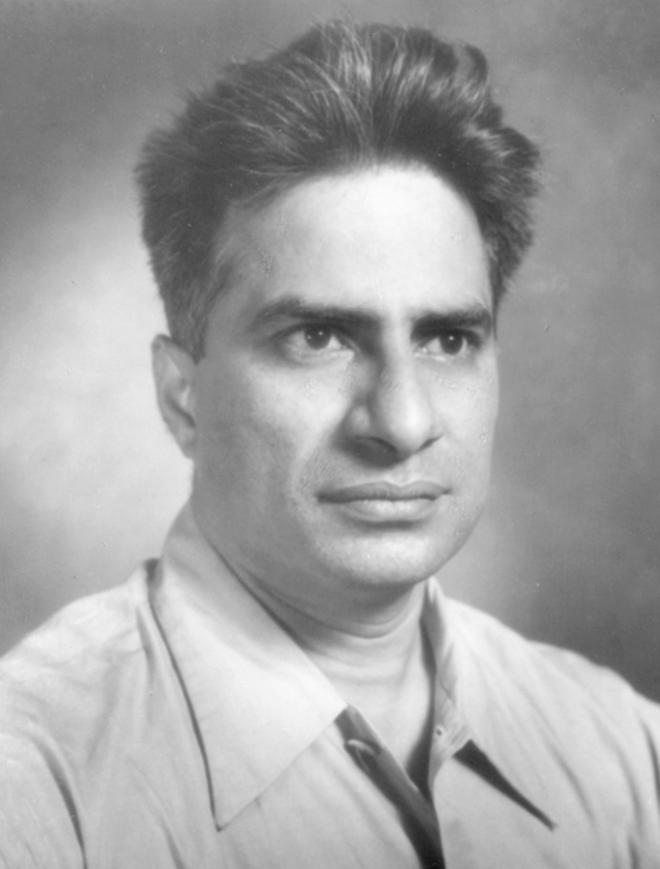

Professor K. Paddayya discusses a book written by British archaeologist and army officer Mortimer Wheeler titled Early India and Pakistan to Ashoka. Two chapters of the book dedicated to prehistory were called “Stones” and “More Stones.” “This is how prehistory was viewed in Indian archaeology till the 1960s, and to some extent, even now,” says the archaeologist and Emeritus Professor of Archaeology at Deccan College, Pune, at a recent talk titled Scientific Study of History and Society, part of a day-long conference held at the National Centre for Biological Sciences focusing on the life, ideas and perspectives of the noted scholar, scientist and historian D.D. Kosambi.

Paddayya, who shared the forum with archaeologist Sharada Srinivasan, professor in archaeology and history at the National Institute of Advanced Studies (NIAS), Bengaluru, offers more insights into the study of prehistory. “Prehistory is regarded as being a very dull subject dealing with the collection of stones… classifying and describing them… giving good photographs,” he says. Kosambi, however, had a very different take on prehistory, as pointed out by Paddayya. “He saw it as being filled with people.”

In a session moderated by Nandita Chaturvedi, Paddayya and Srinivasan offered several intriguing insights into ancient civilisations and societies, ranging from Kosambi’s work and how it has shaped their own, the importance of prehistory in contemporary times, ideas around living history, and more.

Pioneering work

Paddayya refers to Kosambi as a “great public intellectual” and a “great scientist” who, part-way in his career, also began investigating the history of the country, coming up with “real nuggets” of knowledge. “For these things he is very much remembered even now, though he passed away nearly 60 years ago,” says Paddayya.

The most important thing is that his work on the country’s history was adjunct to his career as a scientist, adds Paddayya, who believes there were three phases in Kosambi’s historical scholarship. “For the first 10-12 years, he was trying to relook ancient Indian texts. He did not take them at face value,” he says. He adopted a scientific way of looking at these texts, influenced by the scientific attitude towards history started by Gopal Bhandarkar in the 1880s. “I think he really imbibed it,” believes Paddayya, going into how Kosambi’s historical scholarship vastly differed from the prevailing ones of his time. “He was looking for an approach which would allow him to capture the people of the past, a professional approach towards Indian history,” he says.

He also dispells the tendency to dub Kosambi singularly a man of Marxist Indian historical scholarship. “That was true only upto a point,” says Paddayya, adding that while he was a Marxist, he did not like the “extravaganza” of Marxism. “In other words, he was a cobra without fangs. This is important (to note) when we judge him as a Marxist,” he adds.

He delves into the specifics of Kosambi’s pioneering work, referring to his books such as An Introduction to the Study of Indian History and The Culture and Civilisation of Ancient India in Historical Outline as classics with a very secure place in Indian historical scholarship. “He is recognised for his processes, approach rather than a chronological descriptive approach,” says Paddayya, who believes that in adopting this approach he came down heavily on other interpretations (of history). “Nit-picking is there in his writing, and it is this nit-picking that makes him unpopular.”

Other ideas

Paddayya and Srinivasan also elaborate on Kosambi’s influence on today’s scholarship. “Kosambi pointed to the importance of statistics in looking at the large assemblages before making conclusions about artefacts in a particular context. And that is important in today’s analysis,” believes Srinivasan. In her illustrated talk, she discusses several things, including the similarities between the material culture of certain communities today and ancient ones, details of the Adichanallur archaeological site, some insights into India’s legendary wootz or steel and the continued relevance of spirulina, a food source for the Aztecs and other Mesoamericans, “all that point to long-standing connections and notions of living prehistory that Kosambi was talking about.”

Paddayya, on the other hand, goes into some of the myths about prehistory that Kosambi busted. For instance, the idea of prehistory having a “golden age”, something both ancient Indian texts and some American anthropologists have talked about, where everything was said to be available in plenty. Bringing up the anthropologist Marshall Sahlin’s idea of an “original affluent society“, he states that while Kosambi looked at all these ideas, he didn’t wholly subscribe to it. “He said that yes, there was some progress in prehistoric times, but this progress was partial and slow,” says Paddayya.

Prehistory, believed Kosambi, was a story of triumphs, critical periods and failures. “He got this idea of man being a tool maker, a unique property of man… that we are able to create artificial extensions to our limbs, whether they are stone tools or atoms,” he says, adding that while this enabled man to make some progress and able to adjust better to the environment, it was an arduous process.

Not just big sites

Some of the other ideas Kosambi disputed, according to Paddayya, included the following: that prehistoric Indians were primarily cave-dwellers, that prehistoric man was a mighty hunter and that it was enough to understand all of history through a few big sites like say, Mohenjo-daro and Harappa. “The Indian archaeological record is very rich; it consists of sites of various sizes,” he says, pointing out that limiting it to simply the large ones is a rather limited way of understanding history, akin to understanding an entire people through only its prime minister or president

“What is important is that these sites did not exist in vaccuum. They were all supported by a variety of sites spread all around,” he says, also delving briefly into how Indian society is intrinsically linked to its tribal cultures. “Kosambi was the first to say in a formal way that you cannot understand Indian society and the fabric of India’s culture unless you understand the contribution made by the tribal component,” he says, adding that the whole course of Indian history is incorporation of tribal elements into the mainstream. “In modern times, we think of society in a very homogeneous way. But society and culture we have are composite items,” he says.

Why prehistory

“Why should we study prehistory?” asks Chaturvedi, a question on which both panelists have strong views. Srinivasan, for instance, talks about how, in a country like India, the past continues to be a part of a lived experience. “There are a lot of living traditions,” she says, adding that even in this modern age, with Artificial Intelligence and so on, there is much to learn and discover from the early steps of humankind. “There is a lot of value in understanding how cognitive understanding and creativity and so many things (came into being). You can’t divorce all of that and carry on as if we are now in a different world, “ says Srinivasan, who believes that engaging in the past is enriching for our own development.

Paddayya opines that we don’t talk enough about why we need to study the past at all, in the first place. “I think this is a topic which is not entertained at all in academic circles. In India, we have so many universities; every university has a history departments with many of these departments having archeology attachments,” he says. Also, many universities have philosophy and religion departments, he adds. “But, unfortunately, I have not come across even one occasion where a seminar or conference was held to deal with the topic of why we study the past at all,” he says.

Without tags

He firmly believes that asking this question is very important in our times “when all across the world there is a phenomenon of ethnonationalism.” It is here that we really need to understand why we need the past at all, he says, adding that the prehistoric past is one phase where there are no tags attached, religious, ethnic or cultural. “It is a study of a formative phase of the human story, and it tells us that everywhere in the world, people were eking out their own ways of life, in tune with the ecosystems in which they were raised.”

In other words, this is the anthropological concept of adaptation, where people worldwide adapt to their own environment to arrive at their ways of life. According to Paddayya, understanding this principle about adaptation is liable to make us cautious about rating cultures as high, low, inferior or superior. “You develop a spirit of tolerance in a positive way where you appreciate other ways of life,” he says, arguing that this is one of the most important learnings from the study of the prehistory.