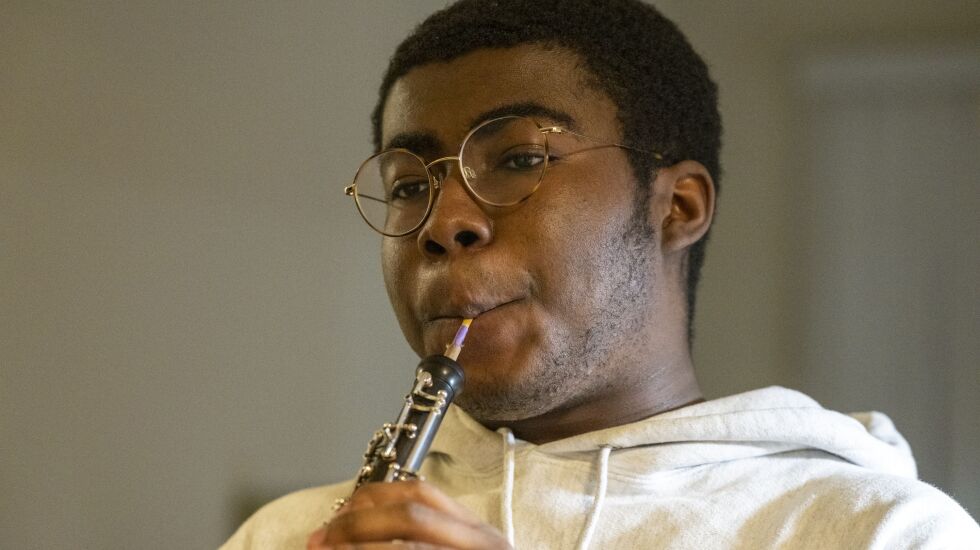

“This whole thing needs to be more angry,” Allen Tinkham, who was at the Chicago Youth Symphony Orchestra podium, told the 18-year-old. “It’s too pretty.”

The rehearsal resumed, this time with Allen providing the snarl and hiss Tinkham wanted as his mother, Denise Allen, who was among the handful of spectators at Symphony Center, kept a watchful eye.

Allen has played at Carnegie Hall and in some of Europe’s great concert venues. He’s applying to some of the top music schools in the United States.

But the most remarkable thing about the talented young musician — who was preparing for a CYSO concert Sunday at Symphony Center — is that he is playing at all after having a stroke in July.

The stroke was a consequence of lupus, an incurable autoimmune disease.

On Monday, the day after this weekend’s concert, Zach Allen expects to have his last session of chemotherapy, which his doctors have used in an effort to control the inflammation that restricted blood flow in his brain and led to the stroke.

It has been a lifetime of off-and-on-again illness that began with a severe infection at birth that doctors twice warned his mother he might not survive.

Denise Allen had miscarried four times. She wasn’t about to lose Zach.

A single mother, she has been a behind-the-scenes dynamo in her son’s life. When a physical therapist began explaining worst-case scenarios to Zach, Mom was there to step in and say, “Tell him what he needs to do to get better.”

“I’m kind of a rally-the-troops, tell-me-what-we-have-to-do-and-let’s-do-it kind of person,” the mother, 59, says at the Skokie apartment where she and her son live. “I’m not a fatalistic person.”

Allen says of her: “I would not be where I am right now without her doing all the stuff that she does.”

Life for him is hectic these days. A senior at Niles West High School in Skokie, he is applying to eight schools, including The Juilliard School in New York. There are recordings to make, accompanists to book, trial lessons with professors, senior portraits, college essays.

In his college application essays, he writes about the struggles he has faced and has overcome: “By age two, I was living in a single-parent household. By age three, I had a series of seizures, signaling the start of yet another medical emergency. My illnesses, though challenging, had always been a series of temporary inconveniences.”

His mother says she noticed her son’s smarts early: He could read at 2 and wrote a simple short story a year later.

In elementary school, Zach started playing viola, then cello.

It wasn’t until he was attending an arts camp in 2019 and heard the hypnotic oboe solo from the second movement of Rimsky-Korsakov’s “Scheherazade” that he knew he wanted to play oboe.

He’s made astonishing progress in that short time, says Erica Anderson, his teacher at the Music Institute of Chicago. She wrote Juilliard’s admissions office on his behalf: “He is the best student I have ever taught in 29 years of teaching.”

Anderson jokes about playing oboe, calling it a “wretched, wretched” instrument. Playing it well is hard enough. But oboists also make their own reeds — a difficult task that might yield just one good one in 12 attempts.

At home, in the living room, a table is covered in slivers and curls of discarded cane from those efforts. Allen owns a two-inch-thick book titled “Understanding the Oboe Reed.”

Of his playing, Anderson says it’s his tenacity and technique that stand out. But there’s also something more.

“When you hear someone like Zach play, you don’t go, ‘Oh, lovely vibrato’ or ‘What a nice turn of phrase,’ ” she says. “You say, ‘That was amazing.’ And you don’t even have words for it.”

Of his mother, Anderson says: “She is not a stage mom. She is just a really good advocate for her kid. They make an excellent team.”

Allen’s ability led to a Zoom coaching session with conductor Riccardo Muti, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s acclaimed music director, in 2020, an experience the young player says was “very inspiring and also intimidating.”

Allen has played with the CYSO for four years, including playing concerts last summer in Berlin, Leipzig, Vienna and Prague.

“It was a lot of fun,” he says. “There was one point during rehearsal when our conductor had to remind us that we were going on tour, not having a vacation.”

Tinkham, the conductor, calls Allen “extremely talented.” When he singled him out at the recent rehearsal, he says he was challenging the young oboist.

“It’s a tricky thing for him because everything he plays is so beautiful,” Tinkham says. “There are times when the composer asks things that sometimes musicians don’t want to do because you’ve spent your whole life trying to sound pretty.”

Allen’s lupus diagnosis came in 2016. It’s rare in children and often hard to diagnose because the symptoms vary so widely. It made his joints painfully stiff. At one point, he lost a lot of weight — about one-quarter of what he weighed. And he suffered through scorching fevers.

“One of the challenges with lupus, we do have some good medicines to treat it, but we do not have a cure,” says Dr. Brian Nolan, a Lurie Children’s Hospital specialist who has been treating him for about a year. “And we do not have very many medicines that are FDA-approved for the purpose of treating lupus, particularly in pediatrics.”

Allen had avoided the disease’s more serious complications until this past summer.

It was just days after returning from the European tour that he had the stroke. It cut blood flow to the part of the brain around the right eye that controls muscle movement, Nolan says.

Allen was lucky. The stroke appears to have left no permanent damage.

But he had to lie flat for an entire week in a hospital bed to avoid sudden changes of blood flow in his brain that might bring another stroke.

“Being completely honest, since they had me lying flat for a long time, the main thing I was thinking about was wanting to eat,” he says.

He has had to undergo six infusions of a chemotherapy drug.

But he shows no sign of illness or fatigue either at home or during a grueling rehearsal.

Before dismissing his young musicians, Tinkham reminds them their concert is just days away and urged them to wear masks when out in public.

“Don’t get sick!” Tinkham tells them.

Allen says he didn’t need to be told. He wears a mask everywhere.

During a short dinner break at rehearsal, he goes with friends to a nearby Potbelly Sandwich Shop. They talk about applying to music schools and the stress that entails.

And he tells a woman who is preparing a video for the CYSO that what people don’t understand about classical musicians is just how much work it takes to get ready for a performance.

“They write it off as talent,” he tells her.

His mother waits outside, then sits quietly in the auditorium for the remaining three hours, there in case her son might need her.

Some time next year, she’ll no longer be hearing the fluttering notes of the oboe in her apartment. Nor the scraping of knife blade against cane to make the oboe reeds.

She’ll miss that, of course. But she says she won’t be the type of mother who has to check in on her son every day when he’s away at college. He will be on his own.

“This is the goal: the great letting go,” she says. “That is what you’re preparing for the whole time. And you want them to be this fully actualized person. And you want them to go off into the world.”