Taking a breath becomes increasingly difficult, foam starts pouring out of your mouth, your vision becomes blurred and your heartbeat slows right down. Then the convulsions take over.

“Then we surrendered to death,” said Dr Salim Namour, describing the symptoms of sarin gas inhalation. He experienced them twice while treating the wounded in Ghouta, Syria, in August 2013, when the regime of President Bashar al-Assad launched a horrific chemical weapons attack on Douma and eastern Ghouta.

“We were destined to live, but not everyone survived.”

Today, Namour heads the Association of Victims of Chemical Weapons (AVCW), one of the organisations that brought a lawsuit which has led to the issue of a French arrest warrant against the al-Assad and three senior officers for the chemical massacre which killed more than 1,100 people.

“The worst effects of exposure to chemical weapons are the deep psychological trauma, the memories of suffocation and the memories of those we lost and loved,” Namour told Al Jazeera. Remembering the terror that befell the hundreds of thousands who were besieged in Ghouta, he said: “They died while they were hungry and dreaming of a loaf of bread, and the children died dreaming of a toy.”

‘Bitterness and disappointment’

Ten years ago, the chemical weapons massacre sparked global outrage, and attention turned to Barack Obama, the then-United States president, who had said that the use of chemical weapons in Syria was a “red line”.

Despite a mountain of evidence against the regime over the use of chemical warfare on civilian populations, Obama’s “red line” culminated in nothing more than the decision to destroy the chemical weapons arsenal in Syria.

Syria agreed in 2013 to join the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) global watchdog and give up all chemical weapons.

This left “a feeling of bitterness and disappointment” for the survivors, according to Namour, as they believed it allowed al-Assad to escape accountability and punishment.

In September 2013, the United Nations Security Council issued Resolution No 2118, which stipulated the need to hold accountable those responsible for the use of chemical weapons in Syria.

The OPCW announced the completion of its destruction of Syria’s chemical weapons one year after the massacre.

Nevertheless, investigations have proved the use of chemical weapons (such as sarin and chlorine) by regime forces in opposition-controlled areas over the following years.

So, AVCW, along with the Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression (SCM), the Syrian Archive, the Open Society Justice Initiative and the Civil Rights Defenders turned to the international jurisdiction of France’s courts in a bid to hold those responsible accountable.

No immunity for war criminals

The decision to issue an arrest warrant for al-Assad comes two years after the lawsuit was filed and evidence and witnesses were presented to the court in France.

The case against al-Assad and the high-ranking military officials was bolstered by firsthand witness accounts and deep analysis of the Syrian military chain of command, said lawyer Mazen Darwish, founder and director of SCM.

Darwish described the arrest warrant as an “historic precedent” as it aims to hold accountable a serving president, who was previously considered to enjoy absolute immunity.

Darwish said the evidence “proves that it is not possible for a military unit to use [chemical weapons] against civilians without an order from the president of the Republic, who is the commander-in-chief of the armed forces”.

Darwish said he is not hopeful that the French trial will bring full justice for the victims, which he believes should take the form of a political transition and a path towards transitional justice. Such a process must be based on the principles of preventing recurrence and revenge, and holding those responsible accountable, he said.

The main goal of filing lawsuits in European courts, Darwish said, is to keep the principle of justice on the table, to enable the voices of victims to be heard and to provide proof that these crimes are real and not just “political allegations” between conflicting parties, as the Syrian regime and its supporters claim.

Halting normalisation with the Syrian regime is also one of the goals of this trial, which serves to remind those who welcome Bashar al-Assad that he is a proven war criminal.

“As a Syrian refugee, I hope to return to my country and be able to live there with my children,” Darwish said. “For any national cause, only the people are the ones who are able to make a difference.”

Remembering ‘town of the dead’

Mohamed Eid, 30, remembers the night when his town, Zamalka, became a “town of the dead” as the deadly gas spread through all its neighbourhoods, causing the deaths of entire families within minutes.

As a media activist, Eid picked up his camera to try to document what he was seeing. “I cannot forget the loved ones and relatives we lost,” he told Al Jazeera. “I saw mothers hugging their children as they died, and a father who could not breathe but was calling the rescuers to help his son instead of him.”

Eid said he would consider any formal trial of al-Assad a “victory”, although he would prefer it to take place in Syrian courts. “But the time is not suitable because the regime is still in power and continues to commit crimes to this day, as we see in Idlib,” he said, referring to the continuous bombing by regime forces of areas outside its control in the northwest of the country.

Amin al-Sheikh, 48, received the news of the arrest warrant with a mixture of “caution and indifference” because he believes that France has interests “other than justice for the victims”. He is angry that France allowed Rifaat al-Assad, the uncle of the Syrian President, to leave France and return to Syria in 2021, despite having been sentenced to prison for using funds diverted from Syria to buy French property.

“They are lying to us and will not do us justice. I would be ashamed of myself if I believed them or trusted them, and I will not change my convictions until I see concrete steps that begin to delegitimise this regime,” al-Sheikh said.

‘Don’t suffocate truth’

The horror of the chemical attacks has never left Mahmoud Bwedany, even years after he became a refugee in Turkey.

The college student was 16 years old when the massacre occurred. “We were accustomed to bombing, but this was different because of the number of victims and the type of weapons that were not often used at the time,” he said.

Bwedany learned of the arrest warrant against al-Assad with mixed feelings, he said. “I felt hope that we would be able to prosecute the criminals and pain over the memories which came back to me.”

After being forcibly displaced to the north of Syria in 2018, Bwedany began work to combat government propaganda and misinformation about the crimes he had witnessed, especially the chemical massacre.

He volunteered with the “Don’t Suffocate the Truth” campaign, which works to raise awareness of what happened in Ghouta and to tell the stories of victims and witnesses through its platforms. Bwedany hasn’t lost hope, he said. “We hope that we will have true accountability for those responsible.”

Other Syrian human rights organisations have also worked to file lawsuits in European courts and to support international efforts to hold the regime and those responsible for war crimes accountable.

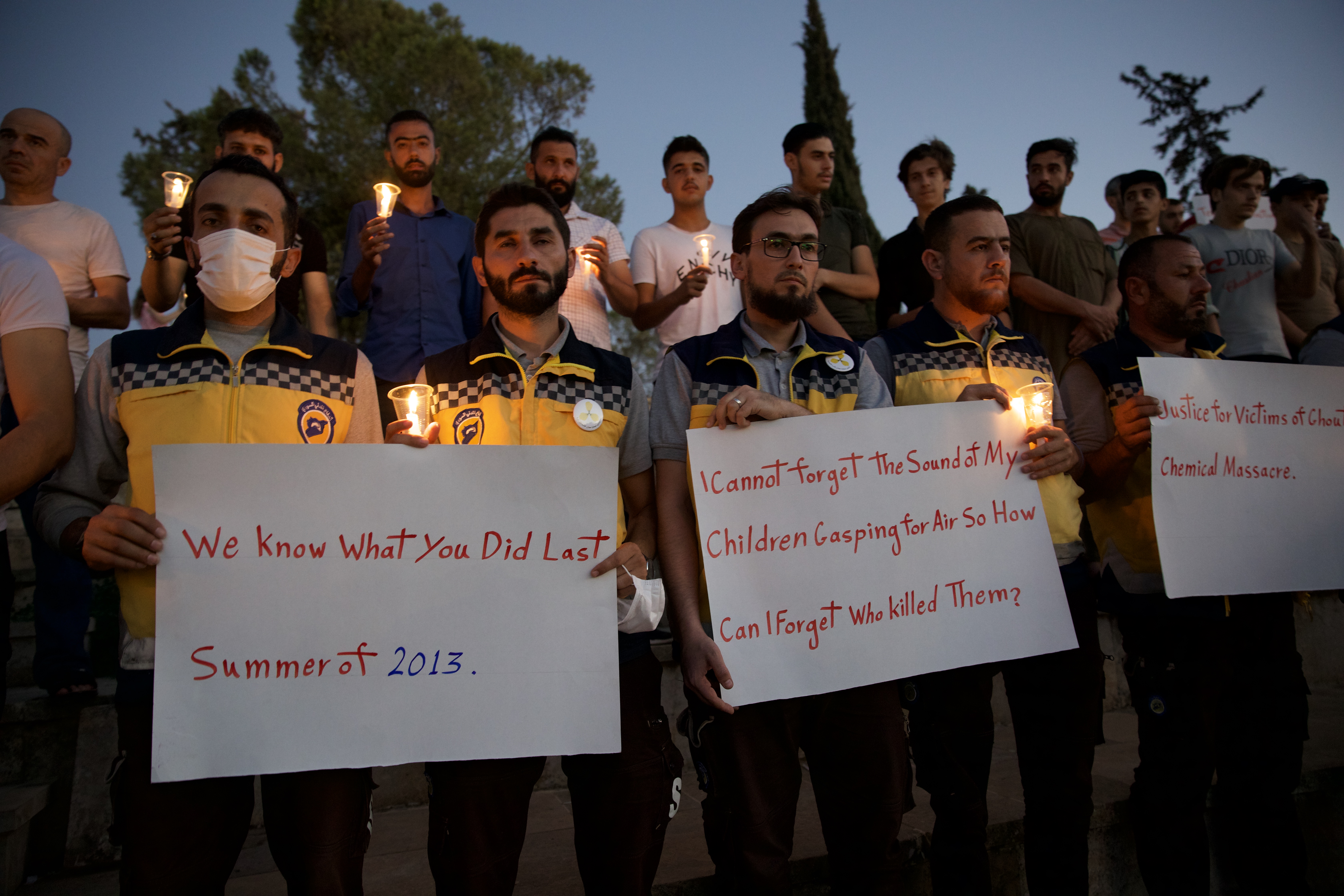

Radi Saad, a volunteer with the Syrian Civil Defence (White Helmets), said any judicial decision aimed at holding perpetrators of violations inside Syria accountable will go a long way down the path of justice and accountability.

At the same time, the Civil Defence is working with the investigation teams of the OPCW to confirm 146 incidents of chemical weapons use in Syria, after confirming 17 locations and proving the Syrian regime’s responsibility for nine of those attacks.