SEATTLE — The first Artemis mission to make use of NASA's moon-orbiting Gateway space station will be Artemis 4, now scheduled to launch in 2028, agency officials confirmed earlier this month.

NASA and its international partners see Gateway as a key platform to support the agency's Artemis moon program and to build the technology required for future deep-space missions. Although the first elements of the small space station are expected to launch before the Artemis 3 mission lifts off in 2025 or 2026, NASA previously said that those astronauts will not use Gateway to "make that mission have a higher probability of success."

Instead, astronauts of the Artemis 4 mission, who will attempt the program's second landing on the moon, in 2028, will be the first ones to live and work in the small lunar outpost, Stephanie Dudley, the mission integration and utilization manager for Gateway, confirmed during an Aug. 2 presentation at the International Space Station Research and Development Conference (ISSRDC) here in Seattle.

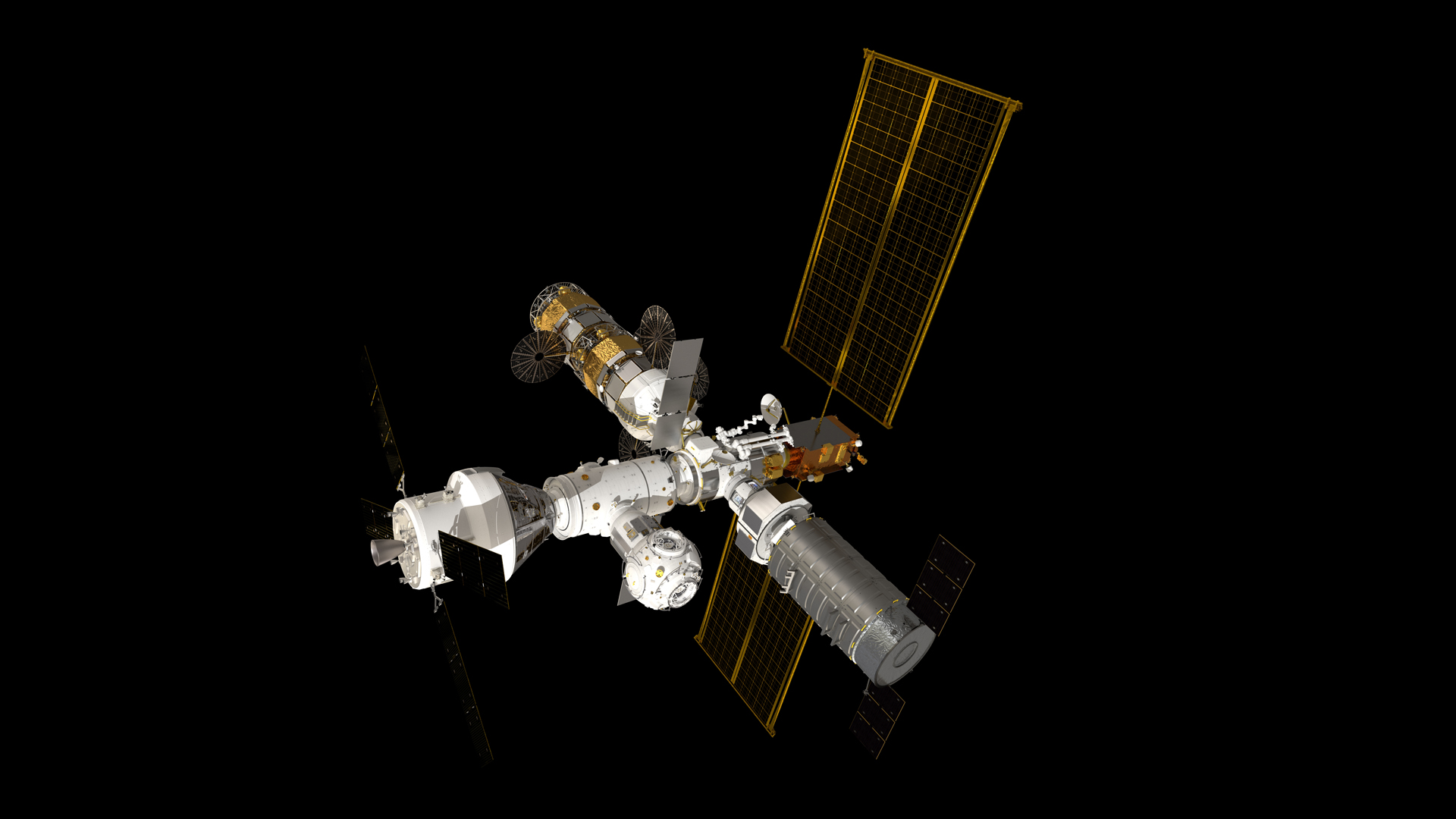

Related: NASA's Gateway moon-orbiting space station explained in pictures

The first two elements of the orbiting space station — one of which is the Habitable and Logistics Outpost (HALO), where astronauts will live and carry out research — are scheduled to be integrated on Earth and launched together in late 2025. By the time the first crewed mission arrives at the small space station, NASA plans to add a second habitable module.

Dudley added that the consequent Artemis 5 mission, currently scheduled for 2029, will carry a refueler for the lunar outpost. The European Space Agency (ESA), in partnership with Japan, will be providing the refueling module as well as the second habitat module. In return, European astronauts will receive three flight opportunities on board Artemis missions to get to and work on the lunar outpost and to touch down on the moon. Two of those missions will be Artemis 4 and Artemis 5, with the third one yet to be announced.

While Gateway will serve as a compact home for astronauts, it is being built such that it can operate autonomously without a crew for up to three years between missions, Dudley said.

That autonomy is quite different from the International Space Station (ISS), which has been continuously crew-occupied for over 20 years and is scheduled to retire in 2030.

"It is not a stretch to say that Gateway is very much a part of ISS legacy," said Dudley during her presentation at the conference.

The crew size on the two space stations will be different, too. While the ISS has hosted a maximum of 13 astronauts at one time, Gateway, which is a fifth of the size of the ISS by volume, caps out at four crew members for a maximum of 90 days.

Dudley emphasized that science experiments performed on Gateway will leverage the station's unique position around the moon and will provide results even without a crew being present.

So far, the initial research experiments announced last year fit this criteria. Taking advantage of Gateway's orbit far away from Earth's protective magnetic field, three instruments will study risks due to radiation from the sun and from cosmic rays. Scientists hope this knowledge can help inform future long-term missions to the moon and Mars.