There aren't too many 97-year olds that retain a capacity for constant reinvention to keep up with the times. But the Le Mans 24 Hours is a great exception to that norm and organising body the Automobile Club de l'Ouest has proven time and again over the years that it is not afraid to embrace change, with last weekend's Virtual edition of the race the latest example.

From the controversial moving back of the walls at the Porsche Curves in 2018, to the flattening of the Mulsanne hump in 2001 and the new pit complex for 1991, its facilities and the circuit itself have modernised to ensure its first-class institution remains just so. Even now, the gravel trap at Mulsanne Corner has been extended ahead of the delayed 2020 edition in September.

PLUS: Is the challenge of Le Mans being diminished?

But arguably its most seismic change came one year earlier than the new grandstand with the insertion of two chicanes onto the 3.7-mile long Mulsanne Straight, a demonstration from the ACO that it was unafraid of making changes to improve safety - even if that meant its most enduring feature would be chopped into three.

For almost 70 years since the first iteration of the 24 Hours in 1923, barreling down the straight at top speed before taking on the Mulsanne kink had been intrinsic to the driver's experience of Le Mans. If you could take the kink without lifting, it was a sure sign that your car was performing well.

But in 1990, the race was no longer about slippery aerodynamic packages that could achieve maximum straightline speed, as more conventional cars with more downforce instead became the norm. The change was controversial in some quarters, not least because - as Autosport reported - the first chicane "was incredibly bumpy". By contrast, the second was "billiard table smooth", prompting five-time winner Derek Bell to remark that "the guy who built the first one must have had a lot more to drink!"

Speaking to Autosport in 1990, Bell said: "The Mulsanne Straight gave you the opportunity to relax and check that all the instruments were working properly. And it was also a very true way to find out if the car was running well.

"If you didn't get exactly the same revs, you'd know that the car was getting worse and you had time to really analyse the problem.

"Now of course we've got to contend with everybody trying to outbrake each other into the chicanes, the slower guys not looking in their mirrors, or anyone that's going around with a slight problem."

Bell certainly wasn't the only one, with Autosport observing that he was merely "one of many to reckon it was more dangerous now, and that the character of the race had suffered".

Tim Harvey, who in 1990 was contesting his third Le Mans in a Spice shared with Fermin Velez and Chris Hodgetts, agrees that Le Mans "lost some of its character" when the chicanes were installed.

"I'm very glad that I got to race on the original Le Mans circuit," says the 1992 British Touring Car champion. "There was nothing like sitting at full-throttle for 60 seconds at 230mph.

"I fully understand why they changed it, but for me it destroyed a little bit the feeling of Le Mans. [In 1990] it wasn't that interesting any longer for me" Stanley Dickens

"It was a bit of a crazy thing to do - especially when you came out of the pits on cold tyres, or in the middle of the night, or in the rain - although you do get used to it because you're doing it lap after lap."

Likewise, 1989 winner Stanley Dickens retains fond memories of the old-style track.

"To be able to take the kink at the end of the straight at full speed was, I think, the ultimate challenge as a racing driver," says Dickens, who shared a works-supported Joest Porsche in 1990 with Bob Wollek and 'John Winter'. "I managed to do that with the Mercedes [in '89] and it was a fantastic feeling once I pushed myself to that limit.

PLUS: How Sauber upset the odds to win Le Mans

"I fully understand why they changed it, but for me it destroyed a little bit the feeling of Le Mans. [In 1990] it wasn't that interesting any longer for me. I preferred it the old style, with all the respect for the high speed and the dangerous track that it was, I didn't like the chicanes."

But there can be no getting away from the fact that a large part of the pre-chicane Mulsanne's appeal was its danger. With speeds pushing 240mph in 1989, accidents when they occurred often had deadly consequences. It had claimed the lives of several drivers including twice runner-up Jean-Louis Lafosse in 1981 and highly-rated Sebring winner Jo Gartner in 1986, while marshals had been killed in accidents in 1981 and '84.

Jaguar's Win Percy had been fortunate to escape an enormous accident in 1987 after a tyre blew, while Mercedes withdrew both its cars after an unexplained tyre failure for Klaus Niedzwiedz in 1988. Few doubted that a change was needed.

"With these kinds of cars and the number of cars, this change was necessary because the old straight was very dangerous and there were big accidents happening every year," says Jesus Pareja, runner-up in 1986 for Brun Motorsport and one of the stars of the 1990 race with the same team.

Steve Farrell, race engineer on the #2 Jaguar of Andy Wallace, Jan Lammers and Franz Konrad, agrees: "I don't remember any driver in Jaguar being unhappy about it because that straight was just so damn dangerous. Nobody in our team was complaining about it, I think it's just everybody bitches when there's a chance, no matter what the change is."

As Farrell points out, even with the chicanes added the Mulsanne Straight "wasn't exactly slow", a fact underlined by the massive accident suffered by Jonathan Palmer when a bolt failed on the rear suspension of his Joest Porsche approaching the second chicane which left his brand-new chassis a write-off.

"It's not often on normal tracks that you got to 200mph and we got to 200mph still three times [in 1990]," Farrell says. "The straights were still plenty long enough."

How to be an ace engineer: BAR F1 and BTCC man Steve Farrell

Wallace, who won the race in 1988, adds: "It was too dangerous without the chicanes. There was some sort of macho thing going on perhaps, 'we liked it without the chicanes, it's stupid with the chicanes'.

"But the insane speeds we were doing on the straight meant if you had anything wrong with the tyre, you wouldn't feel it until it went 'bang'. You were sitting in the car waiting for something to go wrong thinking 'what's that noise, what's that vibration'. You were ready for a tyre to explode and you knew you would just be a passenger if it did. It was the right thing, it couldn't have carried on like it was."

The chicanes had a profound difference on the race. Where previously straightline speed had been the key to a good lap time, leaving the drivers to scrabble for grip around the rest of the circuit, the extra downforce gave the drivers confidence to push.

"Because we didn't have the low-drag car, suddenly things like Porsche Curves that used to be quite tippy-toey with a low-drag car was a bit more normal," says Farrell. "Braking was better for Indianapolis too. It was still a 200mph stop, but it was much more stable."

Wallace recalls: "It became physically a lot harder as well. Not just because you had to brake on the straight for the chicanes, but because you had more load and more speed through the corners."

"With the long bodywork, the car was very floaty, it was like driving a water bed and squirmy in the braking areas" Anthony Reid

Indeed, up to 1989 two-driver line-ups had still been common - Wollek and Hans Stuck had contended for victory that year in the Joest Porsche - but from 1990 a trio would be required to spread the load. Pareja discovered that only too well when team-mate and lead driver Oscar Larrauri was taken ill around midnight, the Argentine only able to drive one stint in the morning.

Nevertheless, despite running on adrenaline from having to drive half the race - "physically, for me it was very, very hard!" - and losing a lap to a flat battery in the pits at 9am, Pareja and team owner Walter Brun had kept the Repsol Porsche 962 in a superb second place when its engine gave up the ghost just 15 minutes from the end.

Receiving a trophy marked Le Mans 1990: Amicale Des Commissionnaires from the ACO - as Autosport put it, "the marshals' consolation price for the most deserving team" - was scant consolation after one of the most gut-wrenching finishes to the race in its history.

That it had been in contention at all owed much to its decision before the race to ignore the advice of the factory to keep the same long-tail, low-downforce configuration that had been used in 1989.

"When we knew the decision was to go with the chicanes, we were maybe the first team that took the decision to go with the short-tail - even though Porsche did not agree with this decision," says Pareja.

"The decision was right, especially for the race because the car was safe and in the rest of the corners was very good. The car was really good, even better than the 1986 car. It was the best race car that I drove at Le Mans."

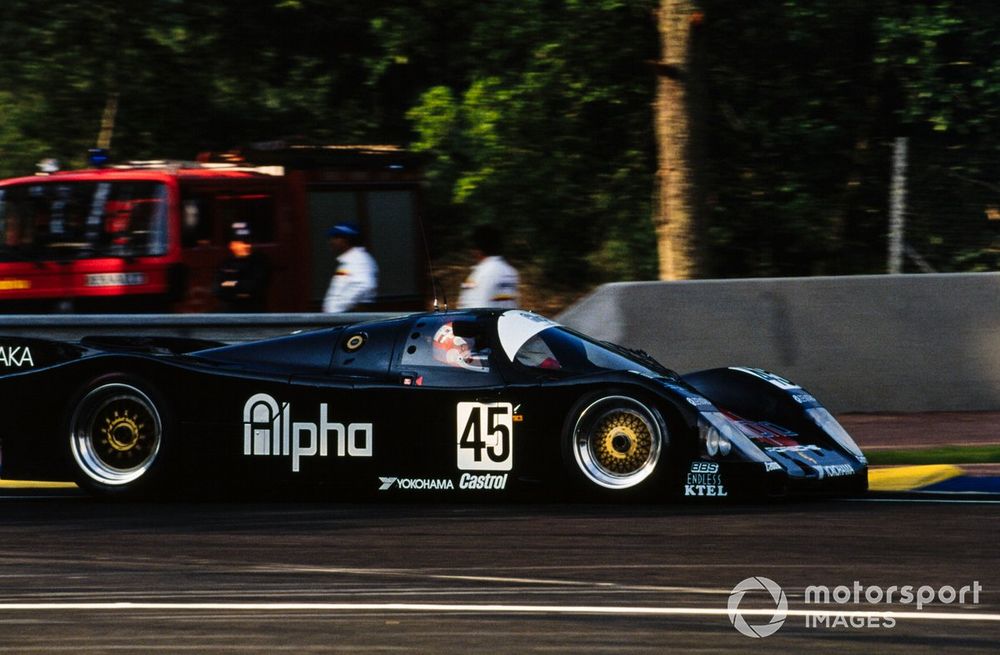

Anthony Reid had been a late addition to the Team Alpha line-up with Tiff Needell and David Sears after Bell was called up to race for Joest. Although a Le Mans rookie, Reid - who, despite having to make an impromptu visit to the medical centre to rinse eyes that had been showered with glass from a broken windscreen, finished third after Brun's disappointment - was left in no doubt after completing a back-to-back test with the long-tail bodywork that the short-tail was indeed the right way to go.

"A lot of it was down to the driver's feeling and I was adamant," he told Autosport on the Race of My Life podcast discussing the 1990 race. "I'd never been to Le Mans before, but I just loved the feel of the higher-downforce set-up. It gave me more confidence and you could brake later for the chicanes, and the tyre runs were very good.

"With the long bodywork, the car was very floaty, it was like driving a water bed and squirmy in the braking areas, clearly you were rubbing out the tyres with the lower downforce set-up."

Indeed, when news reached the TWR Jaguar camp that Joest was persisting with the low-drag set-up, it began to second-guess its own decision.

"I was surprised, I remember that story with Porsche and thinking 'shit, have we missed something here?'" says Farrell. "There was never a debate from the time on what spec the cars would be, there was never options taken to the track. We didn't have a Plan B.

"I believe we must have had a conversation that was black and white. The drivers didn't like the low-downforce car because that V12 engine was such a lump that it always wanted to overtake you under braking. I remember it being a very straight-forward decision."

Sure enough, the Joest cars were troubled by persistent brake problems throughout the race. Dickens, Wollek and 'Winter' finished eighth after Wollek's shunt at the first chicane inflicted tail damage that took 18 minutes to repair, while Bell, Stuck and Frank Jelinski finished fourth, nine laps off the winning #3 Jaguar of John Nielsen, Price Cobb and Martin Brundle.

Autosport surmised: "As the Brun and Alpha Porsches proved, the new Le Mans is no longer a high downforce circuit. The short tail cars proved just the job."

Although engine stress was reduced from spending less time on the rev limiter, the extra strain on brakes and gearboxes resulting from all the extra shifting on entry and exit of the chicanes meant looking after the equipment and not banging the kerbs - all while saving fuel, with usage still capped at 2550 litres - was the order of the day.

"You see a lot of people crash or go off there who obviously wouldn't if they were just going in a straight line, and then they bring gravel onto the track, which could give you a potential puncture, so there was a lot more opportunity for mishap" Tim Harvey

"They do carry some of their own inherent dangers," says Harvey. "You see a lot of people crash or go off there who obviously wouldn't if they were just going in a straight line, and then they bring gravel onto the track, which could give you a potential puncture.

"It was also much busier in the sense that on the old straight, the slower cars would stick to one side whereas now, you've got cars traversing the width of the circuit in the braking areas and entry and exits to the two chicanes and so there was a lot more opportunity for mishap."

As expected, 1990 proved a race of attrition, with Harvey's Spice requiring two gearbox rebuilds on its way to a lowly 18th place, while Nissan lost two cars - including the polesitting R90CK that Gianfranco Brancatelli had earlier damaged in a collision with Aguri Suzuki's Toyota - with gearbox woes. A fuel leak sidelined the third car of Geoff Brabham, Derek Daly and Chip Robinson that led until midnight, after which point the #3 Jaguar led the rest of the way.

Jaguar had seen its own lead contender shared by Brundle, David Leslie and Alain Ferte drop back with multiple unscheduled stops resulting from a water leak, which eventually resulted in retirement just before 7am.

At this point, team boss Tom Walkinshaw switched Brundle to the lead car driven back-to-back by Nielsen and Cobb since the start, which was troubled by a loss of fourth gear and poor brakes. Eliseo Salazar, kept in reserve, would have to make do with a run in the much-delayed #4 car that was also walking wounded. It was a tough call on the Chilean, but for Farrell "a no-brainer".

"You had to have Martin in the car because you know it's going to be looked after and it's going to be the fastest car there," he says. "We always had that in mind that we had to finish. If somebody is going to be faster than you, they're going to be faster than you.

"But the one thing that you could make a difference in those days was being more reliable and the drivers played a big part in that. Martin was absolutely unbelievable on fuel, he could go faster than anyone, more reliable than anybody, less fuel than anybody."

Brundle kept up his end of the bargain, but the same couldn't be said for all his team-mates. The #2 Jag might have been able to capitalise on the leader's worsening gearbox trouble, but nearing 5am, third driver Konrad missed his braking point for the first chicane and lost three laps while repairs were affected.

Needing a new door, windscreen and nose, the #2 car dropped as low as ninth before getting back to third when Pareja's car ground to a halt. Farrell reckons that without Konrad's crash, the wounded #3 car could have come under threat.

"Franz was absolutely devastated that he'd let us down, that's one of my lasting memories," he says. "When you look at the differences in the laps and the amount of time we spent in the pits, that made Franz even more upset because it would have been a close-run thing in the end.

"Franz was a very good team player, a very nice guy, fitted into the team perfectly and made one mistake."

Wallace goes a step further and pinpoints the accident as the moment that "did cause us to lose the race". But since Konrad wasn't given as many laps as his more experienced co-drivers to acclimatise to the car and had to wait until nightfall for his first stint, Wallace accepts that the Austrian was always fighting an uphill battle.

"To be fair to Franz, Jan and I knew the car very well so of course, Franz wasn't quite as fast initially," says Wallace. "He would have got there, but of course, it's a top team and you're expected to perform, so he was pushing like crazy and it wasn't fair on him because he hadn't done the laps that we'd done. Then he made a mistake at the first chicane and smashed the car up.

"It's easy just to do a throwaway, 'it was great before, I was addicted to the speed, it was all great' but in the end I don't buy that" Andy Wallace

"We were second that year and that did cause us to lose the race, but you can't be expected to do the job when you're thrown into that situation. I don't have any ill feeling towards Franz at all, these things happen sometimes in racing."

Looking back 30 years later, Wallace recognises that the brashness of youth contributed to feeling "unbreakable" in his early days. But that illusion, upheld in public, was shattered on the Mulsanne.

"When we won Le Mans I was 27 years old and in your twenties, you've got a very small imagination," he says. "If you find an interview I gave back then, I'll have probably said I didn't like the chicanes.

"It's easy just to do a throwaway, 'it was great before, I was addicted to the speed, it was all great' but in the end I don't buy that. [The chicanes] had to happen and, in some ways, I was quite relieved that it did."