A schoolboy at a private school in Scotland sent out to dig potatoes as punishment ended up unearthing a mysterious treasure from ancient Egypt.

The first of a sesries of remarkable discoveries at Melville House in Fife between 1952 and 1984 are being told in full for the first time by experts at National Museums Scotland.

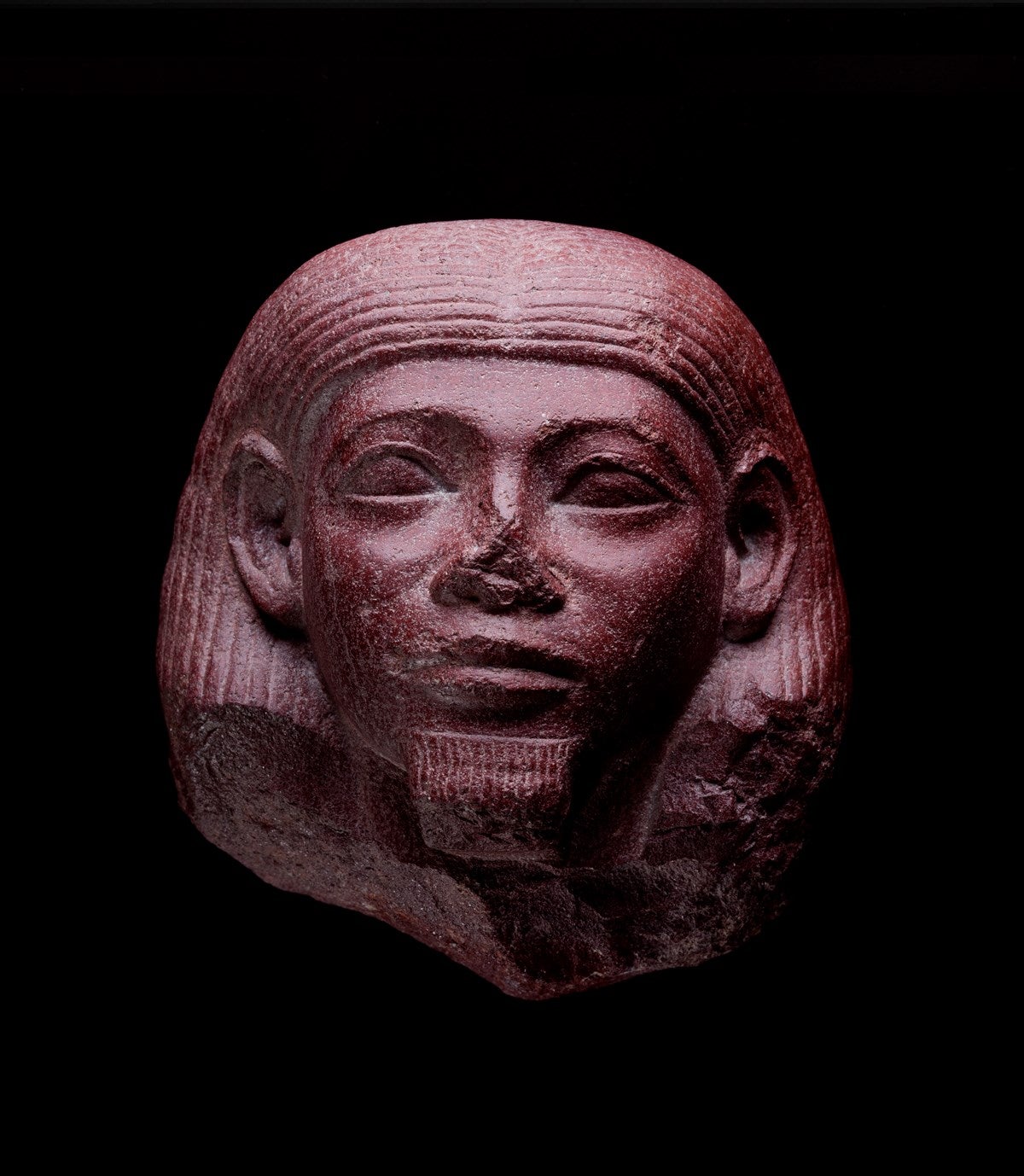

The finds began when the boy from the house, then the private Dalhousie Castle School, dug down and hit a mid-12th Dynasty red sandstone statue head, which he initially mistook for a potato.

Fourteen years later, more treasure was discovered by a boy during a PE class, before, in 1984, a group found another item with a metal detector.

In all, 18 objects have been discovered, with most now in National Museums Scotland’s collection.

Dr Elizabeth Goring, who has since investigated the site, said: “Excavating and researching these finds at Melville House has been the most unusual project in my archaeological career, and I’m delighted to now be telling the story in full.

Head of a statue of a man in sandstone, mid-12th Dynasty (about 1922-1874 BC)— (National Museums Scotland )

“Uncovering ancient Egyptian objects in Fife is clearly unexpected, and the subsequent research to establish the origins of the collection has provided a fascinating tale, albeit one with further mysteries which may never be solved.”

After the first discovery, in 1966 an Egyptian bronze votive statuette of an Apis bull was found in the grounds when a boy taking part in a vaulting exercise during a PE class landed on the statuette, which was protruding from the earth.

The supervising teacher, who happened to be the very boy who had found the sandstone head in 1952, brought the object into the Museum for identification.

Upper half of a faience shabti inscribed for a man named Hor-sa-Iset, Late Period (about 664-332 BC)— (National Museums Scotland )

In 1984, schoolboys found another ancient treasure - an Egyptian bronze figurine of a man - using a metal detector, and brought it into the museum.

It then became clear to experts at the museum that the three objects were connected, and that there had once been a collection associated with Melville House.

Leaded bronze figurine of a priest, Third Intermediate Period (about 1069-656 BC)— (National Museums Scotland )

Dr Goring, a new curator at the musuem at the time, investigated the site and discovered a number of other objects. These included a faience figurine of the goddess Isis suckling her son Horus to part of a faience plaque bearing the Eye of Horus.

Almost 40 years later, experts now have a possible explanation of how these objects ended up buried at Melville House.

Volunteers from NMS and Balfarg working in the grounds of Melville House, 1984— (National Museums Scotland)

They suggest the objects were acquired by Alexander, Lord Balgonie (1831-1857) the heir to the property who visited Egypt in 1856 with his two sisters to try to improve his poor health, after falling ill during service in the Crimean War.

During this period in Egypt, consuls and dealers would visit hotels or passing boats to sell antiquities, so it is possible the objects were brought to a bedridden Balgonie or that his sisters assembled the collection.

Upon return to the UK, they may have been kept for a time at Melville House before being placed in an outbuilding. It’s possible that they were either forgotten in the immediate grief of the young Balgonie’s death or abandoned as too painful a memory of the trip.

Eventually, the outbuilding in which they had been deposited was demolished and those long-forgotten objects went unnoticed in the building debris.

Fragment of a faience plaque depicting the Eye of Horus, Late or Ptolemaic Period (about 664-30 BC)— (National Museums Scotland)

Dr Margaret Maitland, principal curator of the Ancient Mediterranean at National Museums Scotland said: “This is a fascinating collection, made all the more so by the mystery surrounding its origins in this country.

“The discovery of Egyptian artefacts that had been buried in Scotland for over a hundred years is evidence of the scale of 19th century antiquities collecting and its complex history.

“It was an exciting challenge to research and identify such a diverse range of artefacts, including some remarkable objects - the bronze priest statuette is a relatively rare form, while the sandstone statue head is a masterpiece of Egyptian sculpture.”