As the debate within an academic society over freedom of expression rages on, a new survey offers some insight into how lecturers perceive their own ability to speak out

New research on academic freedom in New Zealand’s universities has found stark contrasts in how different academics view their own liberties, with Te Tiriti o Waitangi a particularly polarising topic.

The release of the data comes as a prestigious academic society prepares to hold an emergency meeting over the ongoing fallout from a controversial letter on the scientific status of Māori knowledge.

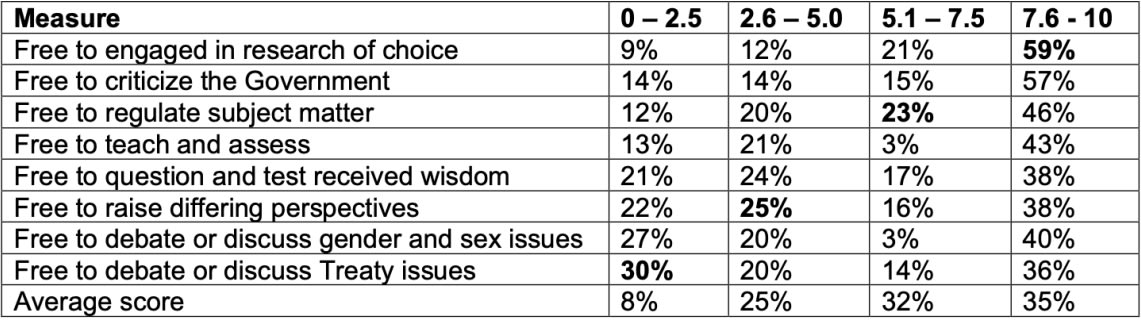

The research, commissioned by the Free Speech Union and carried out by Curia Market Research, asked academics to assess their own freedom on a number of issues on a scale of zero to 10.

The lowest scoring area was freedom to debate or discuss issues around the Treaty of Waitangi and colonialism, with an average rating of 5.4.

On freedom to question and test received wisdom, the average score was 5.9, while for freedom to raise differing perspectives and argue against the consensus it was 5.8.

The areas of greatest perceived freedom were in engaging in research of their choice, with an average score of 7.4, and criticising the Government, at 7.0.

Curia founder and principal pollster David Farrar told Newsroom the majority of the questions put to the academics were based on the provisions of the Education Act in an effort to avoid polarising topics.

Farrar believed the most noteworthy aspect of the findings was not the overall results but the large numbers on either extreme of the spectrum (as shown in the table below).

“If I was a university, that's what I would be very focused on: why is there such a big difference in views amongst the academic staff?”

While it was good academics felt able to criticise the Government, the fairly low scores when it came to questioning received wisdom and raising different perspectives was a concern.

Around 17,000 academics were contacted for the survey, with 1266 responding. Farrar conceded the response rate and self-selecting nature of respondents was a “limiting factor”, but said the broad range of opinions suggested a reasonable cross-section of academia had been surveyed.

Tertiary Education Union national secretary Sandra Grey told Newsroom universities had in recent years appeared “more worried about brand and reputation than about really, truly upholding the critic and conscience function”.

That effect had been most pronounced when academics critiqued their own institutions over issues like internal restructurings or reviews, Grey said.

“Most of the time, staff working on the sector will raise these matters on campus…but sometimes feel they need to go public and say what's going on at their own institution and how that will impact on learners, how that will impact on research, and that from time to time gets a raised eyebrow, or a quick email, or ‘You shouldn't be sharing that information publicly’.”

While many academics were still relatively free to research and teach their subjects of expertise, the move to a market-driven model had acted as a constraint, with some scholars asked to change their areas of research to a topic more likely to be published internationally.

“As a union, we would say that if the words you are about to speak are going to cause harm to others, you should reconsider, because actually, there is nothing in academic freedom that says we should be able to go out and make other people feel belittled, or their mana taken down.” – Sandra Grey, Tertiary Education Union

On the issue of mātauranga Māori, Grey said the union had received more reports from academics who felt under pressure to stop their teaching on the topic than from those who felt unable to express critical views.

“We would defend the right of all scholars to sit down and do proper scholarly debate, but there are limits to academic freedom, the same as any type of speech…

“As a union, we would say that if the words you are about to speak are going to cause harm to others, you should reconsider, because actually, there is nothing in academic freedom that says we should be able to go out and make other people feel belittled, or their mana taken down.”

Grey said the union had been speaking to universities and the Government about the need to educate academics, students and education institutions about their rights and responsibilities when it came to academic freedoms.

Universities New Zealand chief executive Chris Whelan told Newsroom the country’s universities were “committed to upholding the principles of academic freedom enshrined in” legislation.

“These state that academic staff and students are free, within the law, to question and test received wisdom, to put forward new ideas, and to state controversial or unpopular opinions.”

Whelan said the only limits on those freedoms, other than illegality, were breaches of ethical standards such as misrepresenting or ignoring evidence which would normally be determined by other academics.

Universities were also committed to upholding the principles of Te Tiriti, including broader goals of supporting mātauranga Māori (or Māori knowledge systems), and asked that discussion of the topic remain “respectful and mana-enhancing”.

Royal Society saga drags on

Concerns about the protection of academic freedoms were raised last year when the Royal Society Te Apārangi began a disciplinary investigation into the co-authors of a letter to The Listener criticising a proposal to give mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge) parity with other forms of Western knowledge in the NCEA curriculum.

While the Royal Society dismissed the complaints in March, both men (Garth Cooper and Robert Nola) chose to resign as members and fellows citing an "untoward political focus". A group of over 75 society fellows has now written to the organisation demanding an apology to the co-authors over its handling of the matter, as well as a review of its code of conduct and wider organisational structure.

Massey University professor Gaven Martin, who has led the call for an apology and review, said the Royal Society had attempted to “completely shut down debate” on an academically contentious issue.

Martin said a number of academics no longer trusted the organisation following the investigation, while there were broader concerns about how members of its council were appointed and the inability of members to have a say over its decisions.

Newsroom understands the Royal Society is due to hold an extraordinary meeting in Wellington on April 13 to discuss the concerns.

An invitation which went out to members, viewed by Newsroom, said a range of issues had surfaced in recent months, some “but not all” of which related to the Listener letter.

“We would like to hear your views and ideas, and to have the opportunity to discuss them in a free and frank manner. To enable this to happen, we invite all attendees to approach the meeting with goodwill, and for our discussions to be conducted professionally and respectfully.”