A woman kept ending up in the emergency room with excessive sleepiness, slurred speech and the scent of alcohol on her breath, but she had not ingested a drop of liquor. It turns out that microbes in her gut were brewing their own booze — and making her drunk.

Doctors eventually diagnosed her with a rare condition called auto-brewery syndrome. But before that, the 50-year-old had been referred to emergency departments seven times over the course of two years. Each time, her symptoms were similar and made her seem drunk. Her sleepiness, in particular, was troubling, as she'd suddenly fall asleep while getting ready for work or preparing meals. This drowsiness would keep her out of work for weeks and suppress her appetite.

During each visit to the ER, expect the last, doctors diagnosed her with alcohol intoxication. However, "in recent years, she had stopped drinking altogether because of her religious beliefs," doctors wrote in a new report of her case, published Monday (June 3) in the Canadian Medical Association Journal. Her family confirmed that she didn't drink.

Eventually, doctors discovered that the patient's medical history held a clue as to what was causing these bouts of drunkenness.

Related: Can you be intolerant to alcohol?

Prior to having these drunken episodes, the woman had a five-year history of recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs), which come back repeatedly and are very difficult to prevent. To treat these, she was prescribed frequent courses of antibiotics, one after the other.

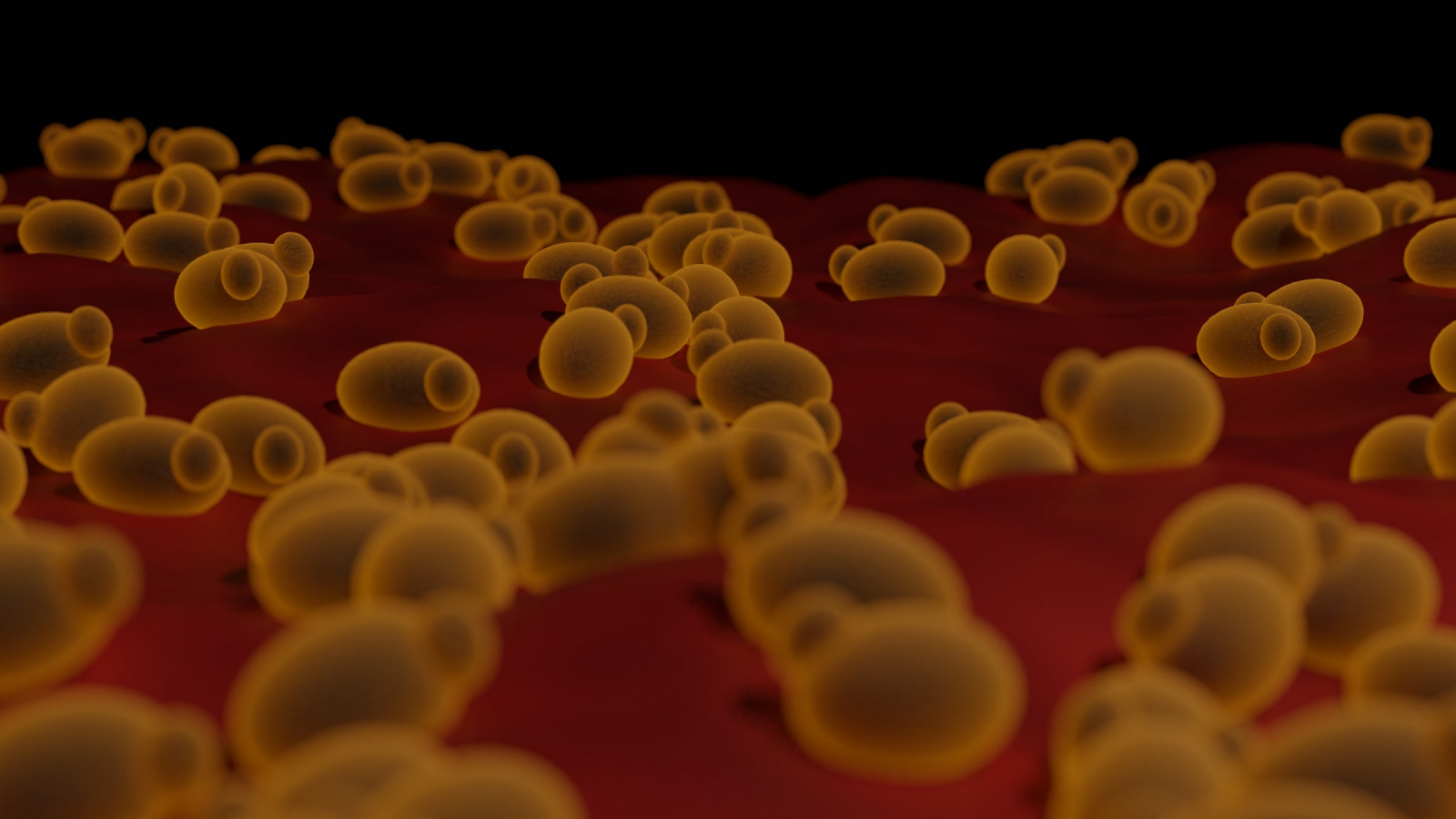

The woman's doctors suspected that, in addition to clearing her UTIs, these heavy doses of antibiotics wiped out helpful bacteria in her gut. This likely cleared the way for various fungi in the gut to take over. Some of these fungi can ferment carbohydrates, essentially brewing their own alcohol.

Auto-brewery syndrome arises when such fungi — including Saccharomyces cerevisiae, or brewer's yeast, and Candida albicans — grow in high enough concentrations and access enough carbs through a person's diet to intoxicate them. Some bacteria have also been tied to the syndrome. People with high blood sugar and a poor ability to break down alcohol are thought to be more prone to the disorder, and these characteristics partly come down to genetics.

It can be difficult to get a diagnosis for auto-brewery syndrome, as it's very rare. Fewer than 100 cases have been reported since its discovery in the late 1940s.

In the woman's case, before being diagnosed with the condition, she was assessed several times by psychiatrists in the ER for signs of alcohol use disorder. However, none of these assessments pointed to signs of addiction. At her seventh ER visit, a doctor suggested that auto-brewery syndrome might be a possibility and started her on a course of antifungal medication. After being referred to a gastroenterology clinic, she was also placed on a low-carb diet to deprive the fungi of sugar to ferment.

After her symptoms went away for several months, the patient upped her carb intake, and symptoms of drunkenness returned. Again, antifungal drugs and a low-carb diet eliminated the symptoms.

The patient was also given probiotics to help restore the helpful bacteria in her gut, and her primary care doctor was advised to give her narrow-spectrum antibiotics for UTIs. Broad-spectrum antibiotics kill many bacteria at once and thus can have a huge effect on the gut microbiome. Narrow-spectrum antibiotics, on the other hand, are much more targeted and can be tailored to the bacteria likely causing the infection.

After the patient went months with no relapses, the doctors tested whether her eating carbs would increase the alcohol levels in her blood. Finding that it didn't, they advised the patient to slowly increase her carb intake, while being monitored by her clinical team.

"Auto-brewery syndrome carries substantial social, legal, and medical consequences for patients and their loved ones," the doctors wrote in the case report. "Our patient had several ED visits, was assessed by internists and psychiatrists, and was certified under the Mental Health Act before receiving a diagnosis of auto-brewery syndrome, reinforcing how awareness of this syndrome is essential for clinical diagnosis and management."

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!