This is the latest instalment in Crikey’s investigative series Kidnapped by the State. For previous instalments, go here.

Some readers may find aspects of this article distressing.

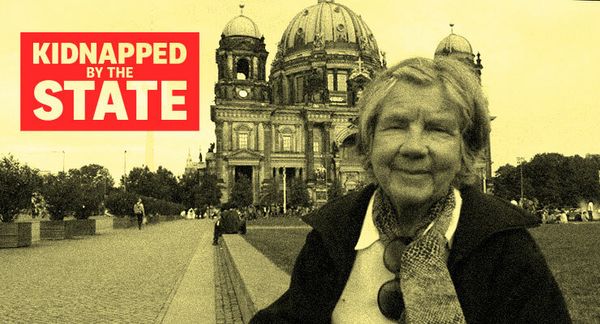

Sean Brandt is struggling to come to terms with what happened to his 81-year-old mother, Jan Brandt. One minute they were travelling the world together, climbing across glaciers in New Zealand, wandering through the cobbled streets of Croatia and sailing a boat across the Caribbean.

But when she broke her hip, everything changed. She was deemed unfit to make decisions for herself due to dementia and was placed under state guardianship.

She went from being an independent traveller to heavily medicated, sedated and living in an aged care home. All of her life decisions, ranging from where she lived to what medications she took and, ultimately, where she would die, were in the hands of a state representative.

The Victorian government had stepped in, with a public guardian in charge of all her personal decisions, and the public trustee in charge of her finances. Their decision went against the advice of Sean, whom Jan had appointed as her medical and financial power of attorney two years prior.

With the consent of the public guardian, a doctor at her aged care facility decided Jan’s dementia had become too advanced to safely eat, drink and swallow without choking, so denied her food and water. She was placed into palliative care with all tube-fed food and liquid removed. Just five days later, amid an ongoing battle to have the guardianship order revoked so that her son could send her to a specialised palliative care facility, Jan died.

Being under the authority of the public trustee cost Jan close to $100,000. The trust charged her around $22,000 in capital commission, $10,500 in accountancy fees, $25,000 in in-house legal fees plus another nearly $30,000 in external legal fees, and $4300 on gardening fees for her property across the two and a half years she was under their management.

As Crikey’s investigative series Kidnapped by the State has revealed, more than 60,000 Australians are touched by state control. Across the country, state public trustees — which manage the funds of those under financial administration — oversaw $14.7 billion in assets, charging astronomical fees for the privilege.

Since Jan’s death in 2015, Sean has been on a mission to find out exactly how his mother could go from a life of independence, with safeguards in place in the form of power of attorneys and a will, to being completely beholden by state representatives. He believes that she would not have deteriorated so quickly had her wishes been respected, and questions the ethics around denying her food and water.

So far, many of his questions remain unanswered and his complaints dismissed by the aged care complaints commissioner, the Australian Human Rights Commission, the Commonwealth ombudsman and medical regulators.

A life well lived

Independent, gutsy and formidable, Jan was a trendsetter at a young age. Born on a rural farm in Victoria, she became a champion equestrian rider as a teen, moving abroad on a riding scholarship in the late 1950s. She was one of the first women in the community to travel, work and own a car and later became a women’s rights advocate and journalist.

Her independence is what attracted her husband, with the couple marrying in the 1960s and having two children. Two kids in tow didn’t slow Jan down: she opened a photography business with her husband which they ran for 35 years.

After her husband passed away in 2013, Jan spent more and more time travelling, visiting the many friends she had scattered around the globe.

“She was very entrepreneurial and she always had such an adventurous spirit,” Sean tells Crikey.

In 2010, Jan had been diagnosed with logopenic progressive aphasia, a form of Alzheimer’s disease that was deemed mild to moderate — though as family doctors said at the time, it only affected her speech, not her cognition.

Neuropathologist and expert in Alzheimer’s disease Colin Masters tells Crikey the condition presents itself in different ways. “If a person can’t communicate, it could be because they don’t receive the information properly, or it’s because they can’t express what they’re trying to say properly,” he said, adding it depended on what areas of the brain were affected. The condition caused Jan to stutter and later forget words or struggle to speak — mostly when she was stressed.

Jan also had incontinence and didn’t drink enough water, which caused her to become dehydrated and suffer recurring urinary tract infections (UTIs) — something that can lead to confusion and delirium in the elderly. But the diagnosis didn’t stop her: she continued travelling, visiting her friends and living her life.

Until a fall changed things forever.

A bias against the elderly

In August 2013, while visiting friends at a pub, Jan slipped on the stairs, fracturing her hip. She was taken to Epworth Hospital — and by November had permanently lost her liberties to the state.

She was assessed by a hospital neurologist and diagnosed with severe dementia. Family doctors don’t believe this took into account her struggles with vocabulary, worsened by stress, while Sean believed she was delirious from a UTI. She was also placed on schizophrenia drug olanzapine, which is used to treat behaviour disorders in elderly patients with dementia; UTI treatments; oxazepam for anxiety and insomnia; and sodium valproate, an anti-seizure and bipolar disorder drug.

Masters says it is best practice to consult with a person’s regular clinician before making a dementia diagnosis and conducting MRI scans and blood tests — but that for the elderly, few practitioners did so.

“Unfortunately for most people by the time they get assessed, they have quite full clinical dementia. There are very few people who want to sit down and actually figure out exactly what is going wrong,” he said.

“The biggest difficulties we’ve got in the aged care sector is that if you’re over 80, GPs and everybody lose interest [in you].”

A spokesperson for Epworth Hospital declined to comment on their dementia diagnosis process, simply saying the hospital is “committed to providing our patients with the highest standard of clinical care”.

When Jan regained her mobility with the help of Sean and his partner Shannon, Sean made preparations to move her permanently into a studio attached to his inner-city home, with Jan approved for an aged care assessment service comprised of 12 weeks of at-home rehab.

But the public guardian had other ideas.

When the state steps in

Jan was placed under the care of a public guardian based on the doctor’s diagnosis of dementia and different opinions by Sean and his sister about what was best for their mother. Sean’s power of attorney was overridden.

“Sean and his mum are incredibly close and unfortunately their closeness was looked at with suspicion, even though he supported her agency,” Sean’s partner Shannon tells Crikey.

Public guardian legislation requires guardians to make decisions on the basis of what they determined to be in the represented person’s best interests, but the state also considers family conflict when appointing the public guardian and public trustee. This was rife: other members of Jan’s family, including her sister and daughter, who lived abroad, supported Jan being placed under guardianship since 2011, believing her condition was worse than Jan or Sean admitted to. Neither responded to Crikey’s invitation for an interview.

Jan’s family doctors didn’t believe a guardianship order was in her best interests.

John McGuiness has been working as an advocate for nearly 15 years, helping those under guardianship navigate difficult legal situations around family disputes, medical treatment and guardianship orders. He was recruited by Sean, telling Crikey Jan’s regular doctors were consulted during the process.

He described Jan’s case as “outrageous”, with Sean’s enduring power of attorney used against her.

A public guardian was given power over Jan’s personal life and medical choices, and the public trustee took over her finances. Concerned she was at risk of another fall and to mitigate family conflict, the public guardian and public trustee recommended she go straight into an aged care home instead of Sean’s studio. A lawyer hired by Sean, along with her regular doctor, confirmed this was against Jan’s wishes.

While public guardians are supposed to take into account a person’s will and preferences when making decisions for them, their preferences can be overridden to prevent serious harm and if those decisions are based in the person’s best interest.

Sean said the public trustee and guardian believed hiring carers and adding mobility equipment to his home were too costly, and that it made more financial sense to send her to aged care.

He said the hypocrisy was shocking: “They said they were moving her to an aged care home because it was financially better for her, but then took almost $500,000 from her account,” he said. Around one-fifth of this was in fees, with the rest spent on insurance, council rates, medical fees and nurse care.

Across the 2013-2014 financial year, Victoria’s Public Trustee managed $70.5 million worth of assets, and made a $3.6 million profit — almost double what it did the year before. A spokesperson told Crikey the state tribunal approved the fees charged. In 2018, following a damning report by the ombudsman, the state trustee announced a number of fee reductions.

Amid rising legal and management fees charged by the state, Jan lost her aged care package and was sent to an aged care home, where she found herself rapidly deteriorating and denied food and water due to issues swallowing and choking.

Tomorrow: How Jan, starved and sedated, spent her final weeks in aged care.

While we have been able to identify Jan for this story due to its particular circumstances, there are legal restrictions on the reporting of some guardianship matters, so please don’t identify yourself or others under guardianship or financial administration in the comments.