The idea of eating aquatic plants might sound unappetizing at first.

However, in certain regions of South East Asia, farm animals and humans have been eating a small plant called duckweed for a very long time.

As researchers in food science, we propose shedding some light on the fascinating world of these little-known plants with a high protein content. We believe they have the potential to revolutionize our diet!

Small plants, big potential

Duckweeds are aquatic plants that inhabit the surface of the world’s freshwater.

There are several species of duckweed, distinguishable mainly by the size of their leaves. These plants are remarkably simple: a tiny leaf floating on the water with a tiny root that is not even anchored to the ground.

This article is part of our series Our lakes: their secrets and challenges. This summer, The Conversation and La Conversation invite you to take a fascinating dip in our lakes. With magnifying glasses, microscopes and diving goggles, our scientists scrutinize the biodiversity of our lakes and the processes that unfold in them, and tell us about the challenges they face. Don’t miss our articles on these incredibly rich bodies of water!

At first glance, duckweed may seem innocuous and even a little too common to be of any interest.

But beneath its humble appearance, this plant has the potential to become a veritable protein factory.

In fact, when grown in optimal conditions, duckweed can contain up to 45 per cent protein, making it an excellent source of this essential nutrient.

Studies have shown that one hectare of duckweed can produce between 10 and 18 tonnes of protein per year. In comparison, soy beans, the most widely grown legume in the world, produce just 0.6 to 1.2 tonnes.

What’s more, these plants have the ability to multiply very quickly. The quantity of duckweed in a pond can actually double in less than 48 hours.

This Olympic level speed of growth raises a crucial question: how can we use duckweed protein for human consumption?

Extracting protein from leaves: a major challenge

The idea of using plant leaves for human food dates back to the Second World War, in a world where people were looking to feed starving populations with this source of protein.

Rubisco, the main enzyme involved in the process of photosynthesis and the protein found in greatest quantities in leaves, has long attracted the attention of scientists.

As well as being the most abundant protein on Earth, Rubisco has a number of other qualities. Its pale colour, lack of taste and odour, and excellent amino acid composition make it an ideal ingredient for the food industry.

For example, did you know that the first prototypes of the famous ‘Impossible Burgers,’ made with plant-based meat, were made with Rubisco?

But a major challenge remains: trapped in the cells of the leaf, Rubisco is surrounded by other compounds with undesirable colours and tastes. This limits its usefulness as a food ingredient.

Although it is possible to produce Rubisco concentrate flours, the process involves a great deal of grinding, heating and chemical separation and each stage entails losses and costs. Currently, to obtain an ingredient that can be used in industry, between 75 and 95 per cent of the proteins present in the leaf are lost.

If we wanted to produce a few tonnes of this ingredient, the quantity of duckweed leaves that would need to be processed would be astronomical, even for these protein champions.

Because of this, Rubisco has never achieved the success it deserves as a food. To solve this problem, our research team set out to free the Rubisco from its shackles. And we succeeded!

How we did it

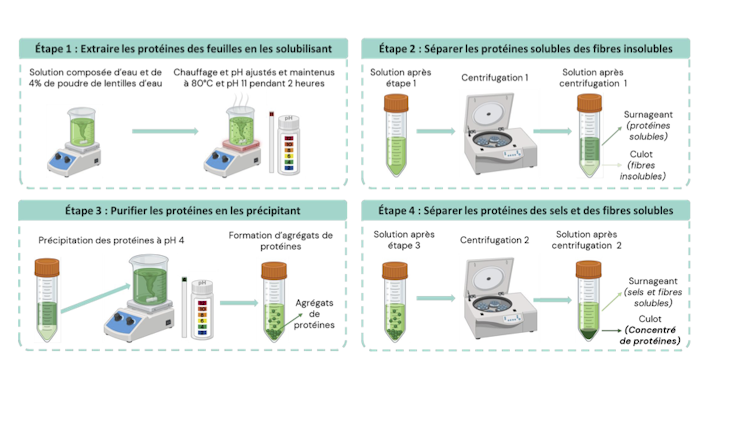

Our team developed an innovative experimental protocol that led to the production of a Rubisco concentrate protein flour. We succeeded in extracting 60 per cent protein, one of the highest yields ever reported in the scientific literature.

Our secret? Mathematics. More specifically, statistical modelling.

Statistical modelling is an invaluable tool for exploring the effects of multiple parameters on a precise response with a very small number of experiments.

In just a few months, we were able to identify the optimum conditions in terms of pH, temperature and concentration in order to maximize the extraction and purification of proteins from duckweed.

The icing on the cake is that this protein concentrate has excellent properties that are essential for any good food ingredient: it is highly soluble in water, and can form foams (like egg whites), gels (like yogurt) or emulsions (like mayonnaise).

Victory!

Towards your plate and beyond

Our research is still in its early stages. But we can already see a promising future for duckweed proteins.

It could find multiple uses in food formulation, but also in the field of nutrition and human health. Some of the molecules they contain could help to reduce high blood pressure.

In short, thanks to its high content of versatile proteins, duckweed could very well end up revolutionizing our diets. And, above all, it will help shape a more sustainable and nutritious food future for everyone.

Laurent Bazinet has received funding from the Consortium de Recherche et Innovations en Bioprocédés Industriels au Québec (CRIBIQ), grant 2020-050-C67, and from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), Projet Alliance "Integrated valorization of coproducts by ecoefficient food technologies in the context of a circular economy (Consortium VITALE)," grant ALLRP561008-20.

Tristan Muller ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.