According to a recent study, coastal shipping produces a fifth of the carbon emissions (well-to-wheel) of road freight. Rail also performed well, with about a quarter of trucking emissions.

Despite this, trucking accounts for nearly 80% of New Zealand’s heavy goods transport, and a 94.5% share of the total emissions from heavy freight transport.

The dominance of trucking follows the expansion of the road network, which enables trucks to move relatively fast, travel to hard-to-reach locations and adjust routes to meet the flexibility required for just-in-time deliveries.

But despite its advantages, trucking is associated with external costs, including higher carbon emissions than other modes of transportation.

This study represents the most comprehensive comparison of freight emissions for different carriers to date for Aotearoa New Zealand.

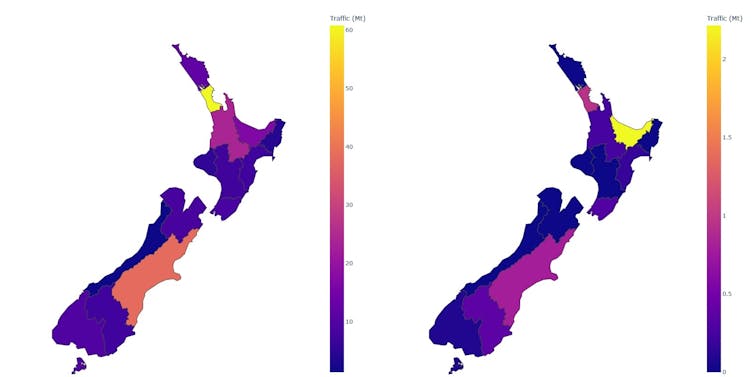

Before we evaluate decarbonisation pathways, we need to have a solid understanding of the freight system. To this end, we have created a transport dashboard to visualise the carbon footprint of freight movements within New Zealand.

With decarbonisation commitments firmly locked into legislation, we have hard deadlines to cut emissions. Failure to do so will represent a risk to New Zealand’s economy and likely require taxpayer money to buy expensive international carbon offsets.

Read more: Why New Zealand should invest in smart rail before green hydrogen to decarbonise transport

We need to reconsider how we operate

A shift to less energy-intensive freight transport modes like coastal shipping and rail represents a possible pathway to reducing fossil-fuel dependency.

But despite the benefits of sea and rail transport, it remains unclear how to achieve the shift to new infrastructure and technologies. A key requirement is access to an efficient multi-modal network that integrates ports, inland terminals, distribution hubs, roads and railways.

We can achieve economies of scale by transporting larger volumes of goods, which would lead to cheaper costs per unit. As the European Commission noted:

The challenge is to ensure structural change to enable rail to compete effectively and take a significantly greater proportion of medium and long-distance freight.

Our research was focused on creating a detailed understanding of New Zealand’s current heavy-freight system. Emissions reporting extended beyond the direct combustion of fuels and accounted for vehicle-embedded emissions. We also consolidated data from multiple sources, which helped with calculating energy demand and direct and indirect emissions for every freight mode.

For example, we found the majority of a truck’s lifetime emissions (almost 80%) come from the fuel it consumes. This is why it’s important to prioritise operational aspects and switch to non-fossil propulsion technologies.

Read more: Transport emissions have doubled in 40 years – expand railways to get them on track

Where to from here

It will take considerable investment to expand or upgrade transport networks and optimise freight corridors in terms of energy use and emissions. Beyond our research, we’ll need complementary work to investigate the technical and economic feasibility of non-fossil propulsion technologies.

We’ll have to take a holistic approach to map feasibility hurdles (technical challenges, material needs, system architecture and integration) that must be overcome.

The ultimate goal is to decrease fossil fuel demand and emissions while ensuring long-term economic and trading resilience.

Equally crucial is the participation and support from stakeholders. Freight transport is a complex system characterised by multiple interests (policy makers, shippers, freight forwarders, port and rail representatives) with sometimes conflicting views. Strategic planning also needs to acknowledge consumer preferences and their impacts on energy use.

The latest report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) elaborates on this:

Drawing on diverse knowledges and cultural values, meaningful participation and inclusive engagement processes—including Indigenous knowledge, local knowledge, and scientific knowledge—facilitates climate resilient development, builds capacity and allows locally appropriate and socially acceptable solutions.

Beyond the focus on emissions cuts, we need to engineer freight systems with a high capacity to adapt, so they can sustain trade and wellbeing while operating at much lower energy levels. The notion of adaptation also has to extend further than the current focus on physical protection against extreme weather events.

Read more: IPCC report: the world must cut emissions and urgently adapt to the new climate realities

The tools and technologies to decarbonise freight transportation in New Zealand are available now. The problem lies in their integration and the understanding of the trade-offs at stake. Freight transport emissions can be reduced through cost-effective investments in multi-modal infrastructure and alternative propulsion technologies.

However, it is essential for future initiatives to operate within the biophysical limits of our planet, as emphasised in the IPCC’s report:

Technological innovation can have trade-offs such as new and greater environmental impacts, social inequalities, overdependence on foreign knowledge and providers, distributional impacts and rebound effects, requiring appropriate governance and policies to enhance potential and reduce trade-offs.

Patricio Gallardo works for EPECentre. In 2022, EPECentre carried out a project to estimate Greenhouse Gas Emissions from freight movements within New Zealand. The project was funded by Swire Shipping.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.