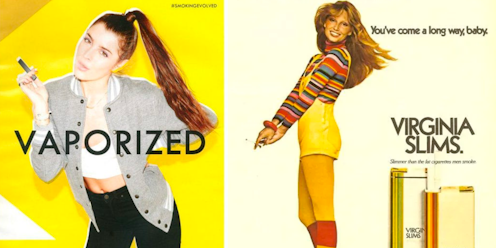

When smoking first became popular we were told it was healthy, it was heavily marketed (including to young people) as being cool, and the time it took for us to learn otherwise was long, and came too late for many. Unfortunately, it seems history is repeating itself with vaping.

Before the invention of machines to make cigarettes, they were hand-rolled – with an experienced roller making around 240 cigarettes an hour. When mechanisation arrived in the late nineteenth century, early machines could make 12,000 per hour. Eventually, they could churn out 1.2 million an hour.

This made smoking immensely affordable, accessible to those on even meagre incomes. These machines would go on to become perhaps the worst development in public health history.

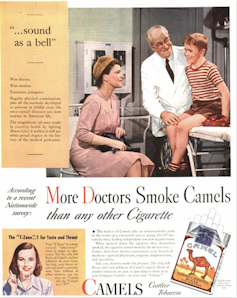

Combined with mass cigarette advertising, including the infamous 1940s “More doctors smoke Camel than any other cigarette” which successfully distracted the population from early concerns about harm, cheap cigarettes saw smoking prevalence skyrocket globally.

Two in three long-term smokers died from their addiction.

Ever since, governments have been struggling to introduce potent controls on Big Tobacco. The World Health Organization’s 2003 Framework Convention on Tobacco Control has an entire section devoted to ways of minimising industry interference.

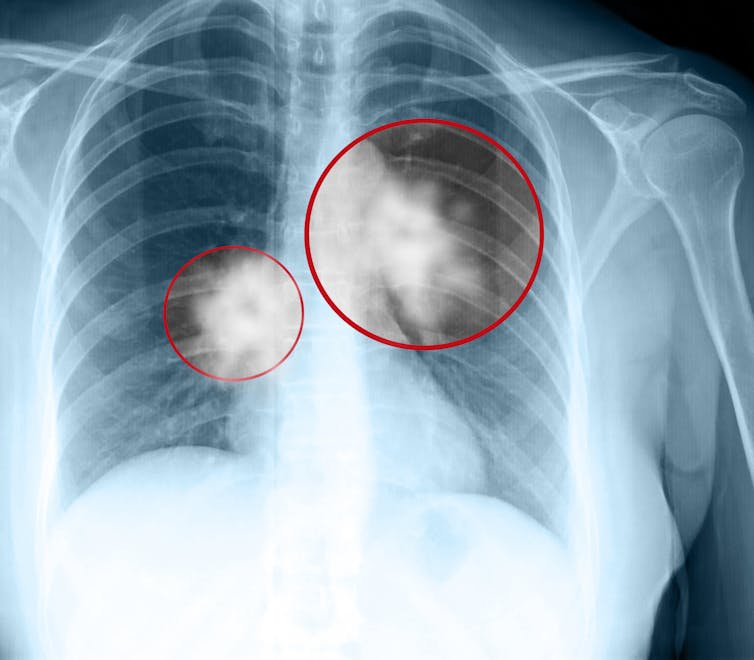

Lung cancer was rare

Despite heavy industrial air pollution in cities dating from the early 1800s, lung cancer was a rare disease. US surgeon Alton Ochsner, recalling attendance at his first lung cancer autopsy in 1919, was told he and his fellow interns “might never see another such case as long as we lived”.

He saw no further cases until 1936, and then saw another nine cases in six months. Given the smoking boom that occurred in the US with World War I, Ochsner was quick to assume cigarettes were to blame.

Since the 1960s, lung cancer has been (by far) the world’s leading cause of cancer death. Lung cancer (almost all of which can be attributed to smoking) was responsible for 18% of all cancer deaths in 2020, with the next most frequent killer, liver cancer, at 8.3%.

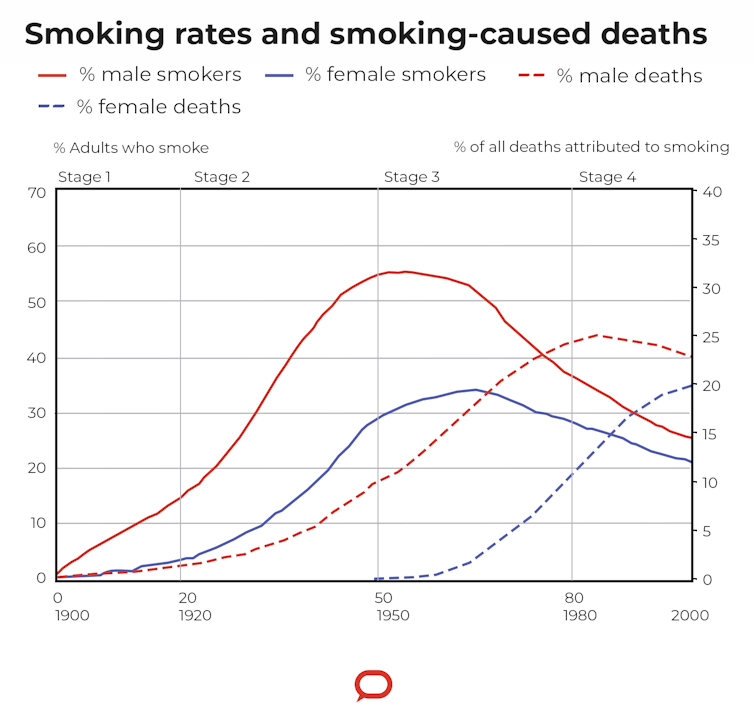

Most public health graduates in recent decades are familiar with a famous 1994 graph illustrating the shape of the tobacco-caused disease epidemic across time. The graph shows four stages of the smoking and disease epidemics.

Nations in the first 20 year-long stage have accelerating smoking but negligible tobacco-caused disease. By the fourth stage, smoking is declining but disease is growing more rapidly than ever. These gaps are known as latency periods in epidemiology.

Mesothelioma caused by breathing asbestos fibres also follows this pattern. The latency period between initial exposure and the onset of symptoms can be up to 50 years.

Enter nicotine vaping products

Vaping has only been widespread for about ten years. So, if it causes serious diseases such as lung cancer, cardiovascular or respiratory disease, we would expect very few cases by now. This has not stopped cavalier declarations that vaping is “95% less dangerous than smoking”.

This statistic is still used by many, despite the paper that gave birth to this factoid admitting there is a lack of evidence for most of the criteria used to assess vaping’s harms.

There is a great deal of early evidence now available that vaping is likely to be anything but benign. For example, recent reviews on vapes have found they contain carcinogens known to cause lung cancer, are correlated with asthma, and impair our vascular systems.

Knowledge about the deadly toxicology of tobacco smoke emerged over decades. By contrast, the many thousands of flavouring chemicals in vapes present bewildering challenges for regulators.

In 2021, the US Flavour and Extracts Manufacturing Association declared “E-cigarette manufacturers should not represent or suggest that the flavor ingredients used in their products are safe […] because such statements are false and misleading”. Regulators have never allowed asthma drug inhalers to contain flavourants.

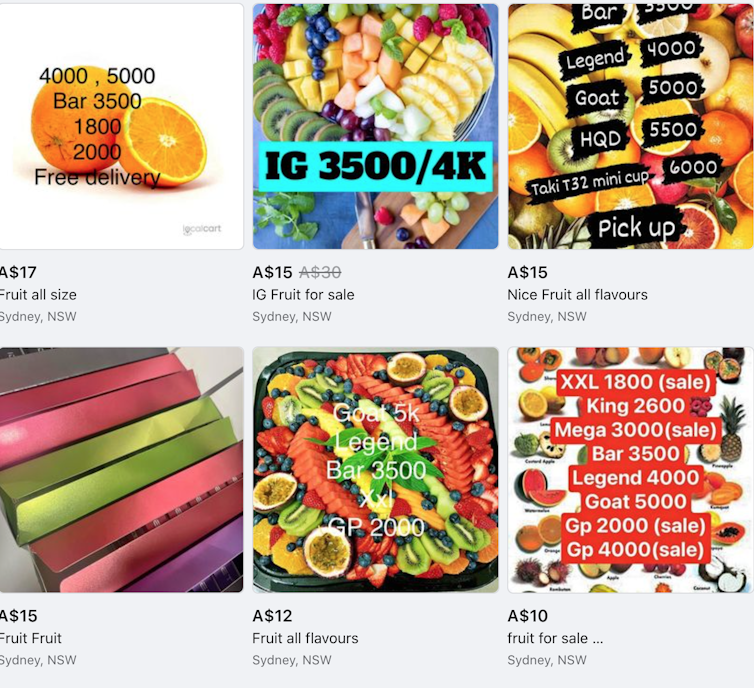

All forms of tobacco advertising and promotion have long been banned or seriously restricted in many nations. But vaping emerged in the internet era where regulation presents formidable barriers. Social media today are awash with vaping promotions, with illegal vapes flagrantly being sold as “fruit” on Facebook Marketplace.

Research has shown indoor areas with many vapers contain airborne particulate matter concentrations higher than crowded bars in the days when smoking was permitted. No airline in the world permits in-flight vaping.

Read more: Passive vaping – time we see it like secondhand smoke and stand up for the right to clean air

Repeating the same mistakes

With children’s vaping accelerating dramatically in Australia, Canada, the US, United Kingdom and New Zealand, governments are scrambling to find solutions to the problem they created by rash, rushed policies.

Vaping advocates argue laws and regulations for vapes should be no more harsh than those that apply to cigarettes. So with no restrictions on where cigarettes can be sold, we see tobacco industry-led efforts today in Australia trying to allow vapes to be sold under the same conditions.

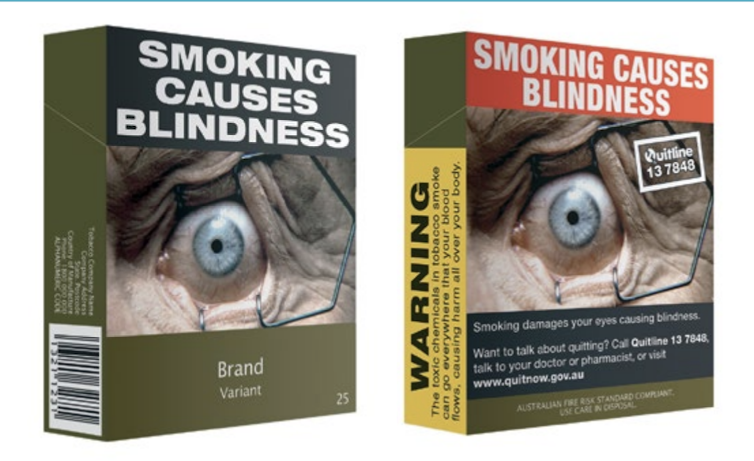

The first baby steps in Australian tobacco control were tiny health warnings that appeared in 1973. It then took 40 years to fight for all the policies and quit campaign funding that have together taken smoking down to its lowest ever levels.

This 40 years was due to both early ignorance of the latent size of the emerging smoking disease epidemic, and sustained pressure from the tobacco industry to defeat, delay and dilute every policy that threatened to reduce smoking.

Just as the tobacco industry for decades denied targeting children, we are seeing almost identical claims and strategies being used by vaping industries today. And it’s important to note all major tobacco companies are now also manufacturing vapes, so it’s not just the same game, it’s the same players.

It’s often said that if cigarettes were invented tomorrow, and we knew now what we didn’t know then, no government in the world would permit their sale (let alone allow them to be sold in every convenience store). But this is what is happening now with vapes.

With pharmaceutical products that save lives, treat illness and reduce severe pain, we allow only people with a four-year pharmacy degree to sell them, and only to those with a temporary licence (a dose- and time-limited prescription) issued by a doctor. With cigarettes, we foolishly allowed them to be sold everywhere.

All health departments in Australia, most major political parties, nearly every health and medical agency in Australia and many internationally, including the WHO, are saying vapes should be strongly regulated.

Vaping advocates argue we need vapes to help smokers quit, but the evidence they do that is weak.

Currently vaping devices are widely available, but those including vaping liquids containing nicotine are only legally available with a prescription in Australia. This doesn’t stop people buying them easily online or from many convenience stores blatantly breaking the law.

The previous health minister tried to ban personal importation of nicotine vapes and liquid, and the current one expressed interest in doing the same before a period of public consultation via the Therapeutic Goods Administration.

As with Australia pioneering plain packaging laws in 2012, if the import ban is implemented we will again quickly be emulated by other nations. And again detested by the tobacco giants.

Read more: Learning about the health risks of vaping can encourage young vapers to rethink their habit

Simon Chapman in the past has receive funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council and the US National Institutes of Health.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.