Microplastics are omnipresent. These small pieces of plastic, which are leftover from all sorts of consumer products, have been detected in oceans, historic soil samples, and virtually everywhere on the planet. Naturally, they’ve also been found in almost every human organ: In lung tissue, blood, breastmilk, and more. And now, a recent study published in Toxicological Sciences has shown a light on yet another body part they’re ending up in: testicles.

An earlier study had previously assessed the presence of microplastics in human testes and semen. Animal studies have also looked at the interactions between microplastics and fertility, in mice specifically. But in the recent study, a group of researchers at the University of New Mexico collected samples from both human and canine testes. The 23 human testes were taken from men who died in 2016, and the 47 dog testes came from neutering.

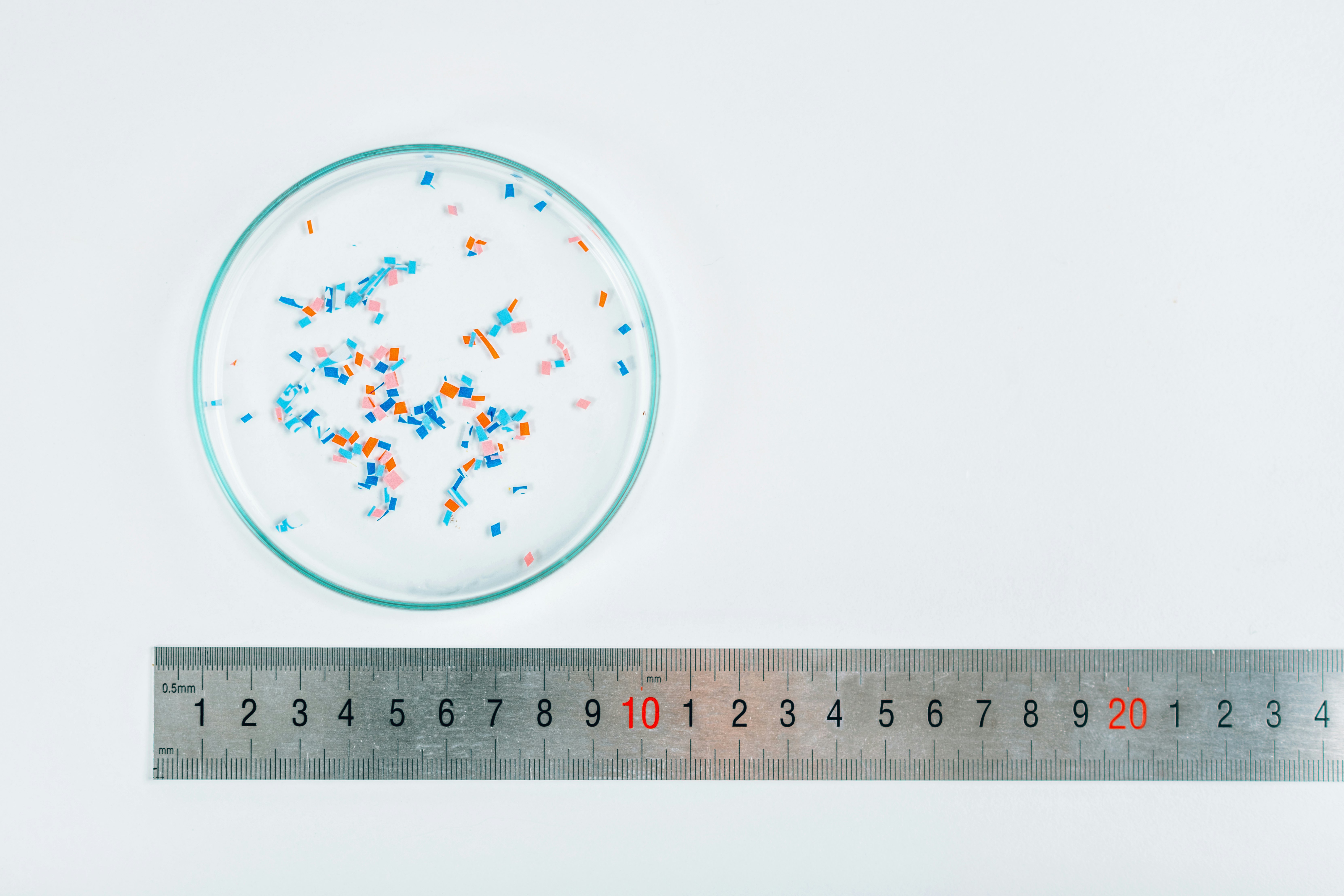

The scientists analyzed the samples using a technique called Pyrolysis-Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry, in which they checked both the presence and concentration of microplastics. They detected microplastics in every sample collected –– both human and canine. This result shocked researchers.

“At the beginning, I doubted whether microplastics could penetrate the reproductive system,” Xiaozhong Yu, a professor at the University of New Mexico told the Guardian. “When I first received the results for dogs I was surprised. I was even more surprised when I received the results for humans.”

Although there was significant variability between individuals, the average microplastic levels in humans was about three times of that in dogs. The researchers were also able to identify the different types of plastics present in the samples. Polyethylene (PE), the compound used for plastic bags and bottles, was dominant in both dogs and human testes. That’s unsurprising given that it's the most widely used plastic. Researchers also detected PVC, a plastic used in pipes, medical devices, and more.

This finding is especially pertinent given the recent reports that sperm counts are on the decline worldwide. In the study, researchers were only able to test sperm counts in the dogs, as the human samples were already dead. They found that the higher the concentration of PVC, the lower the sperm count. This is in line with previous reports that show PVC — and plastic in general — has the ability to affect the endocrine system.

Future studies will be needed to evaluate the effects of such microplastics on human sperm production and function.