On a hot Friday afternoon, students at Lenart Elementary Regional Gifted Center dance with zest in the parking lot as a DJ plays music. They are excited to get out of their public school classrooms for a walkathon, a fundraiser for the school in West Chatham on the South Side.

Three times around the school equals a mile, and for each mile students earn money for their school. So far, the kindergarten class is in the lead, pulling in $1,000 in the last hour.

“We are up to $17,000, which is more than we did last year,” says Theisha Perkins-Obafemi, parent of bubbly second grader Grace.

The event is meant to be fun, but it’s also critical for the school. Chicago public schools like Lenart don’t get by on taxpayer money alone.

All CPS schools get a set amount per student to run their buildings, with schools serving mostly low-income students getting extra — but it’s not enough. The state says CPS only has 68% of what it needs in state and local dollars to properly fund its schools.

To make up the difference schools are increasingly turning to private money. But they don’t all have the same fundraising might. The majority of outside money is collected and spent by a small number of schools where less than half the students are low-income, WBEZ found in an analysis of private fundraising expenditures at district-run schools. These schools are primarily on the North Side in affluent neighborhoods. And the amount they’ve raised has skyrocketed over the last decade.

CPS doesn’t track all outside money flowing into schools, but much of it lands in one fund in school budgets that appears to have emerged in 2008. The money comes from fundraising, renting out school parking lots, student fees, grants and other sources.

A total of $175 million was spent from these funds from 2010 through 2021, according to a review of CPS budget data. The amount peaked between 2016 and 2019, during a time of unprecedented budget uncertainty that resulted in mid-year cuts. It then dropped during the pandemic.

Low-income students make up the majority of the student body at 82% of CPS’ elementary schools. The remaining fraction — just 77 schools, some in very affluent neighborhoods — spent two-thirds of the amount raised. Even among these 77 higher-income elementary schools, it is only those in the wealthiest North Side areas — such as Lincoln Park, North Center and Lake View — that raise and spend significant funds. In 2019, only 13 schools spent $300,000 or more in outside money.

WBEZ focused on elementary schools in its analysis, which does not include charter schools. Elementary schools account for $103 million of the money spent since 2010.

The analysis also uncovered how schools are spending the private money. In a relatively new development, many schools are using the money to partly or entirely fund teacher or staff positions. And, in a district with billions of dollars in outstanding repairs, some schools pay for their own sound system, auditorium repairs and playgrounds rather than wait years for their turn for capital dollars.

Ald. Rossana Rodriguez-Sanchez (33rd) said fundraising helps explain why some schools in her North Side ward seem to have significantly more resources than others.

“It really creates this sort of horrible culture,” she said. “The schools that are gentrified, that are wealthier, are going to have the most resources. And then the schools that don’t have ‘friends of’ groups or don’t have enough resources to be able to donate to the schools, those schools are not going to have access to those things. So it is maddening.”

It’s not just an issue in Chicago.

“Wealthy parents are raising large sums of money to improve their already advantaged schools,” according to Hidden Money: The Outsized Role of Parent Contributions in School Finance, a 2017 report by the Center for American Progress. “Schools with robust and well-funded PTAs spend thousands of dollars per student to provide even better programming, including field trips, new computers, art and music instructors, and new supplies for teachers.”

Meanwhile, schools without large parent donations must pull funding from core instruction or sacrifice needed social emotional supports to pay for these things, the report said.

This spring, as schools confronted budget cuts due to enrollment loss, many parents said schools that do hefty fundraising were better protected. Others argue fundraising creates inequities and allows some parents to escape some of the realities of an underfunded system.

CPS officials say just looking at fundraising “across this large district [doesn’t] tell a full or accurate story.” They note schools serving low-income students get extra federal, state and district resources.

They also highlight extra resources for students with special needs, those learning English and with other unique needs.

“CPS has long considered how to provide equity — to not only ‘even the scales’ but to better support those students who are facing greater obstacles. Our leaders remain committed to this value,” CPS said in a statement.

District officials also point to a CPS-affiliated organization, the Children First Fund, that collects corporate and philanthropic donations and distributes them to schools. In a statement, the fund’s executive director said it “exists for this very reason — to address resource inequities that impact our CPS students and school communities.”

Past CPS records show little direct support for schools from the Children First Fund, but the director says it raised $24 million this year. That paid for violence prevention, healing circles in schools and for stipends to families in crisis, among other things. The fund also tries to match individual schools that do not have parent fundraising groups with philanthropic sponsors, according to the fund director.

A tale of two schools

The difference in what schools can raise translates into a difference in programming.

Compare two top-performing elementary schools — Lenart, serving mostly working-class families on the South Side, and Lincoln Elementary, serving wealthier Lincoln Park families on the North Side.

Lincoln’s fundraising partly supports one and a half art teachers and two music teachers. Plus, it has a band program that students can pay to participate in.

Lenart has less than 300 students and, because enrollment is tied to budgets, it has little wiggle room. When Principal Angela Sims had to cut her full-time art teacher, she used some of the money they raised to bring in an instructor from the Hyde Park Art Center to visit each class once a week for an hour.

“You have to start to think creatively and how you can still provide art or music to students,” Sims said. “So you look for community partners. It’s much more affordable. So if a teacher would cost the school, let’s say $80,000, you can find art for $20,000 for the school.”

Even though only a third of the students are from low-income families, the majority of parents can’t drop a $1,000 check and make up the difference between what CPS can afford and what the school community needs.

Sims is also wary of depending too much on fundraising.

“I don’t think we should be fundraising to save someone’s job,” Sims said.

Lincoln has more than 900 students and is in Lincoln Park. Principal Eric Fay said fundraising is an integral part of what the school “has to do.”

In 2019, Friends of Lincoln raised $532,667, according to tax documents. The school also has a music association that offers band for a fee and collected $178,569.

Fay said the money is needed because the school doesn’t get any federal Title 1 money, which schools with large low-income students populations receive. For a school Lincoln’s size, that could be upwards of $400,000 extra a year. Even with fundraising, Lincoln’s budget is smaller than other CPS schools of similar size.

But its students also need significantly less support than typical CPS students. Only 10% of Lincoln students are low income, less than 6% have special needs and less than 5% are learning English. Meanwhile, 78% of CPS students overall are considered low income, 15% have special needs and 20% are learning English.

Lenart also gets little benefit from Title 1 money. It received $25,000 in Title 1 dollars in 2020 — not much more than what it can fundraise in a year.

Schools in low-income neighborhoods lack connections

Title 1 schools say they also struggle financially, despite the extra resources. And many can’t fundraise at all.

In 2022, Joplin Elementary in the Auburn-Gresham neighborhood received $281,000 in Title 1 funds, and that helps it maintain staffing. But Interim Principal Miyoshi Brown said the school needs more.

“It’s the extras that could make the difference,” such as covering field trips for students who can’t afford them, Brown said.

She said her community lacks the connections needed for fundraising. Most of the students are on free and reduced lunch. Unemployment is high in the community.

Many local businesses are owned by people who don’t live in the community and aren’t engaged with the school.

“If you’re middle class, you can have middle-class friends or upper-middle-class friends, you can raise more money. But those who are in economically underserved areas, we tend to just make do and get by,” Brown said.

It’s schools like Joplin, on the city’s South and West sides that are disproportionately hit by the lopsided fundraising.

“There are basic needs that are hard for a lot of families to meet — like getting to school every day,” said Elaine Allensworth, director of the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research.

The fundraising juggernaut schools rely on social capital, she said. Connections and relationships beget financial resources.

“If you’re a member of the school community, you have relationships with other people that would be happy to contribute to your fundraiser,” Allensworth said.

What drives the fundraising powerhouses

Strong fundraising can be essential in a district where most students don’t go to their neighborhood school, forcing schools to compete for students. And in wealthier neighborhoods, the public schools also are competing with private schools where fundraising is expected.

In gentrifying communities, fundraising also can help encourage new residents to enroll their children.

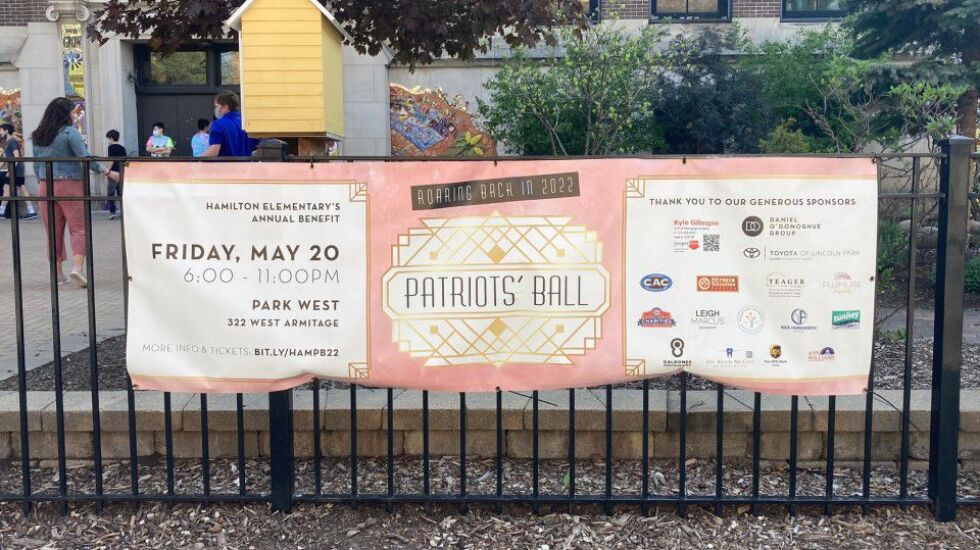

At Hamilton Elementary in Roscoe Village, the school’s strong fundraising apparatus helped to dramatically change the North Side school — not only because of what it could buy but also because of the message it sent young parents in the community.

Meeting at a coffee shop this spring, three mothers said they love Hamilton. One big selling point is the school’s fine and performing arts focus.

“We liked that it’s a little bit smaller school compared to a lot of the other schools in our neighborhood,” said Lynn Hamill, who has a first and third grader at the school.

It’s a dramatic change from when Hamilton was threatened with closure in 2009. The school barely had 200 students, less than half the enrollment from a decade earlier. The neighborhood was getting more affluent, but not enough area parents were sending their children.

A former principal gathered a group of parents and formed the Hamilton Action Team. “And they were doing fundraising for cleaning up the playground and actually having a playground. Apparently, it was just really old equipment, unsafe,” said Holly Kohli, current president of the team.

These days, Hamilton parents regularly bring in more than $200,000. It helps the school pay for staff to watch students during recess and for books and technology.

The school again has more than 400 students. But the student population has changed. It’s now 71% white, up from 26% in 2009. And low-income students dropped from 63% to less than 10% now.

That is one of the potential downsides of fundraising. It can help revive a school, attracting wealthier families to a neighborhood, which in turn pushes out lower-income families who then don’t benefit from the new resources.

The moms from the Hamilton Action Team say they recognize how advantaged they are and are working on a partnership to help a North Lawndale school that also has a fine arts focus. Parents at other big fundraising schools also worry about the inequities the money creates but feel it’s necessary to give their children what CPS doesn’t provide and attract neighborhood parents.

Parents at another North Side school, Volta Elementary, say they are trying to raise money without alienating current parents. Volta’s students come from mostly low-income Latino and Asian families, many of them immigrants.

“If you’re a single working mom or just a working mom or working parents and don’t have access to donating big funds or volunteering all of your time for the school, it makes it really hard,” said Julie Leung, who transferred her daughter to Volta from a nearby school that is a fundraising powerhouse. “You don’t feel like you belong.”

Volta formed a “friends of” group a few years ago but has also focused on getting public money and grants. In 2019, they had a big win when they convinced their alderman to use some of the ward’s budget for a new green space with a pollinator garden.

Different realities

The hard reality is that most Chicago public schools are like Volta, where fundraising for big ticket items isn’t possible. In the end, most have to make do with the limited dollars CPS provides them.

Kellogg Elementary is a neighborhood school in North Beverly. Parents have hosted talent shows, jazz soirees and sold plant seedlings and say they’re great for building community. The money has gone toward laptops for students — not the school addition they want to reduce overcrowding.

“There’s a private sort of de facto element with the school setup” in CPS, said Tanika Pierre, the president of the elected Kellogg Local School Council. “All the CPS students are not the same. All the CPS schools are not the same.”

Her friend and fellow Kellog parent Emily Lambert agrees.

“We need things that cost millions of dollars, and a school with 150 families cannot and should not be in the position of making these capital improvements,” Lambert said. “We have systemic needs that we can’t fundraise for.”

Sarah Karp covers education for WBEZ. Natalie Moore is a reporter on WBEZ’s Race, Class and Communities desk.