Enigmatic, C-shaped antler carvings from France's Stone Age have puzzled scientists for over 150 years, but now a modern experiment investigating these artifacts may have revealed their purpose: They were likely crafted to be Paleolithic finger grips for spear-throwers, a new study finds.

The discovery was made by using similar crescent-shaped devices to throw dart-like projectiles at archery targets. The success of these trials suggests that the objects — made of deer antler and called "open rings" — were once attached to now-rotted-away wooden spear-throwers: weapons also known as atlatls that were used to throw large darts at high speeds, according to the study, published March 22 in the Journal of Paleolithic Archaeology.

Although the discovery hasn't been verified by finding a Paleolithic atlatl with the open rings attached, "we've mostly convinced ourselves," said study co-author Justin Garnett, a doctoral student in archaeology at the University of Kansas who did the research with co-author Frederic Sellet, an archaeologist at the university.

"The rings come from the kinds of sites where gear maintenance would have been performed, and they look like finger loops and work well as finger loops," Garnett told Live Science in an email. "That said, we should always be cautious when assigning functions to prehistoric artifacts — there's always the chance that we may be mistaken."

Related: 8-year-old girl unearths Stone Age dagger by her school in Norway

Finger loops

The first open ring was discovered among Upper Paleolithic artifacts at Le Placard Cave in southwestern France in the 1870s. Since then, 10 more have been found, all in France, as well as one "preform" — an open ring that was in the process of being carved but still attached to the rest of the antler.

Only the preform has been directly dated, showing it was made about 21,000 years ago, by early modern humans of the Magdalenian culture or the Badegoulian culture that preceded it.

Each open ring is an arc a bit more than 1 inch (3 centimeters) high and about 2 inches (5 cm) long; each of the two ends has a horizontal tab, giving it the shape of the Greek letter omega. Some archaeologists suggested that the rings may have been ornaments or fasteners for clothing.

But the shape seemed distinctive to Garnett, who has made spear-throwers for more than 20 years. "I've always enjoyed making things with my hands, and target sports like archery," he said. "When I saw a picture of an open ring, I immediately thought it looked like a finger loop, just based on my experience replicating and using spear-throwers."

Spear-throwers

A spear-thrower or atlatl is a wooden shaft with a hook or spur at the end that attaches to a dart; it gives users extra leverage, enabling them to throw heavy darts several feet (1 to 3 meters) long with precision and at high velocities. Bone spurs from atlatls have been found at several Paleolithic sites, indicating that the weapon was widely used by hunters from about 20,000 years ago. "It is easier to make darts for hunting big game than to make a reliable bow with comparable power, and you can carry more darts than spears or javelins," Garnett said.

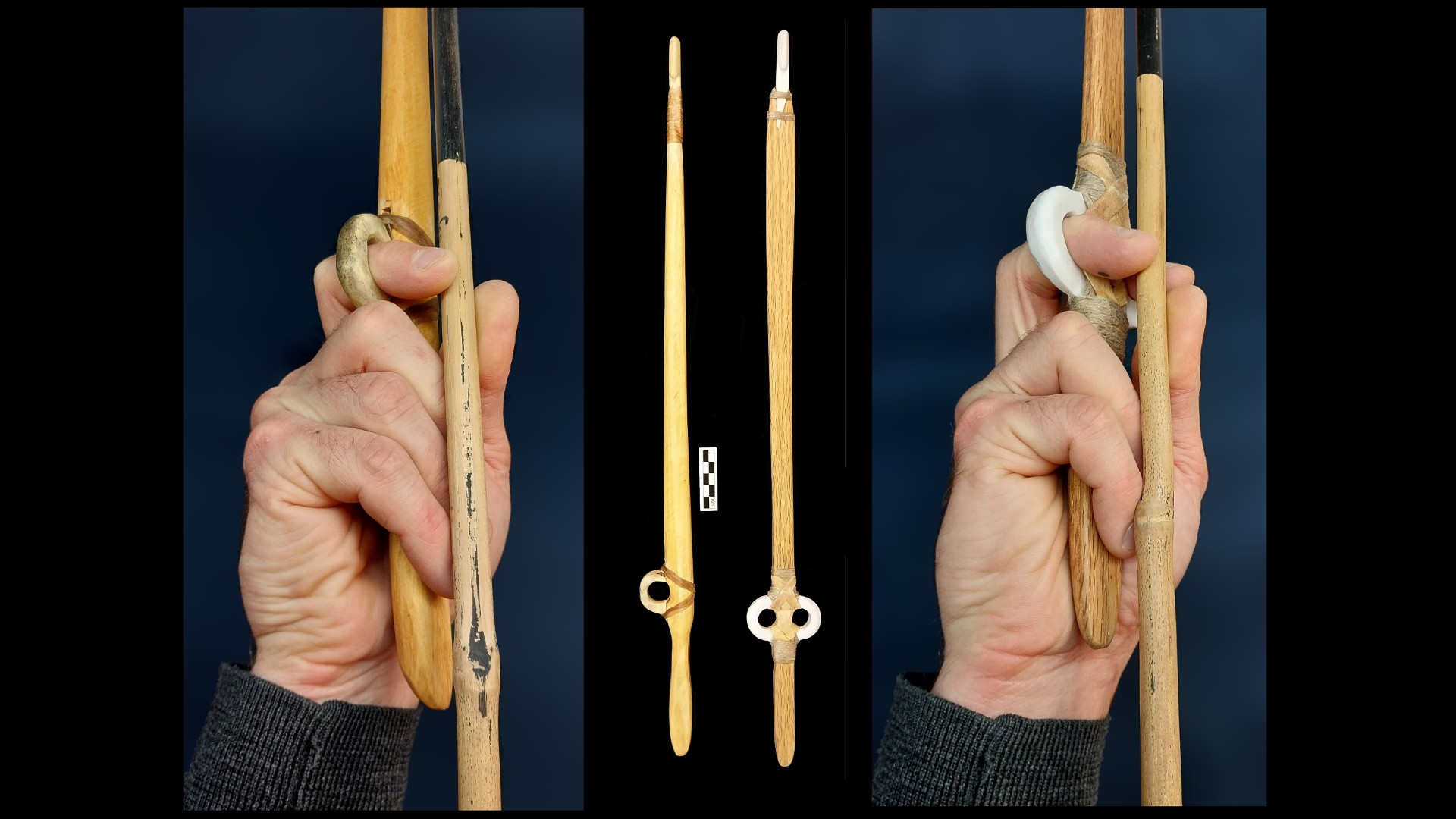

The new study also describes Garnett's experiments with replicas of the open rings — made from cattle bones, elk antler and 3D-printed plastic — that he attached to replica spear-throwers.

Garnett then spent a year hurling darts from the spear-throwers at archery targets, and related the results to earlier studies that had used pig and deer carcasses; using targets avoided ethical issues, he said. He determined that the open rings functioned well as finger loops, and may have been better and more durable than loops simply made from animal hide. The experiments also showed that the wear on the replicas was similar to the wear seen on the open rings.

The new study is "fascinating," Pierre Cattelain, an archaeologist at the Free University of Brussels and an expert in Paleolithic hunting with spear-throwers, spears and bows, told Live Science in an email.

Cattelain, who is also the scientific director of the Center for Archaeological Studies and Documentation and the associated Malgré-Tout Museum in the Belgian town of Treignes, was not involved in the latest research.

He remembered suggesting in the 1990s that the open rings may have been finger loops for spear-throwers. However, his hypothesis was "not accepted at the time," Cattelain said. "So I completely agree with the authors of this article on the interpretation and conclusion."

Editor's note: Updated at 10:24 a.m. EDT on June 5 to note that while researchers used deer and hog carcasses in earlier studies, they did not use them in the new study for ethical reasons.