Usually when someone mentions El Niño, people probably immediately think about weather-related disasters. Yet what if I tell you that this incredibly strong ocean-atmosphere phenomenon can do something globally magnificent?

Following an El Niño-fuelled storm that started spinning over Japan, Surfline’s forecast team made a surprising discovery that re-intensified and kept travelling around the globe until, 2 weeks and 12,000 miles later, it reached Portuguese shores.

More info: surfline

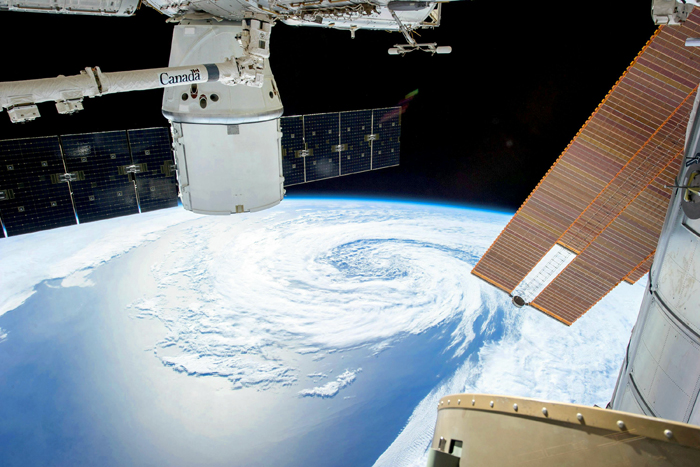

El Niño-driven storms sent a huge ocean swell, bringing joy to all the surfers around the globe

Image credits: Pixabay

Before we get to know more about the sensational discovery made by Surfline’s forecast team, let me introduce you to El Niño – a wild climate phenomenon that describes the unusual warming of surface waters in the eastern Pacific Ocean.

The phenomenon was recognized by fishermen close to Peru coastline as the appearance of unusually warm water. Researchers have no real record of what indigenous Peruvians called the phenomenon, but Spanish immigrants called it El Niño, meaning “the little boy” in Spanish. With time, it came to describe irregular and intense climate changes rather than just the warming of coastal surface waters.

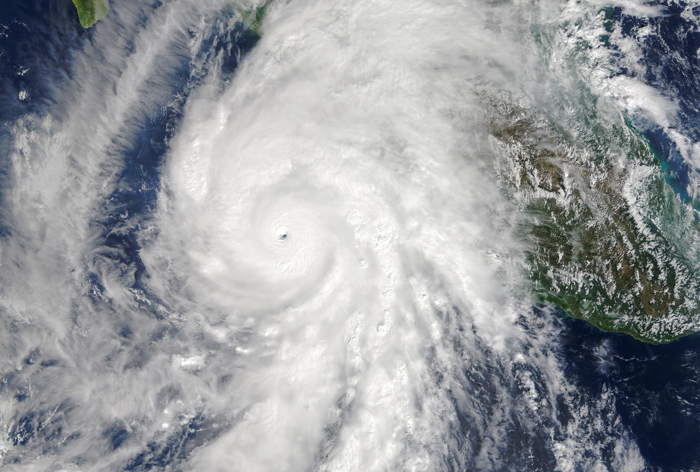

Image credits: Met Office

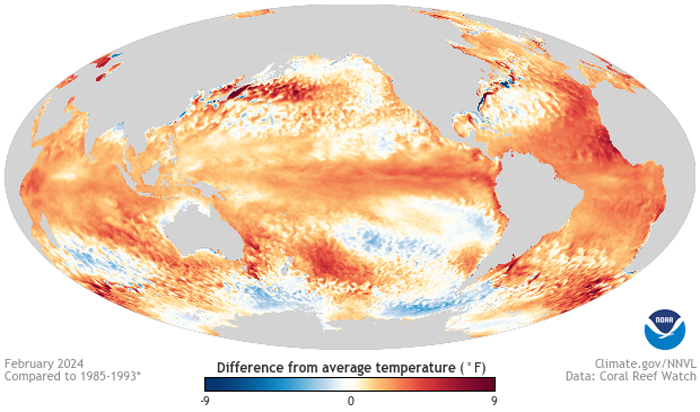

It is important to mention that El Niño events are indicated by sea surface temperature increases of more than 0.9° Fahrenheit for at least five successive three-month seasons. The intensity of El Niño events varies from weak temperature increases (about 4–5° F) with only moderate local effects on weather and climate to very strong increases (14–18° F) associated with worldwide climatic changes.

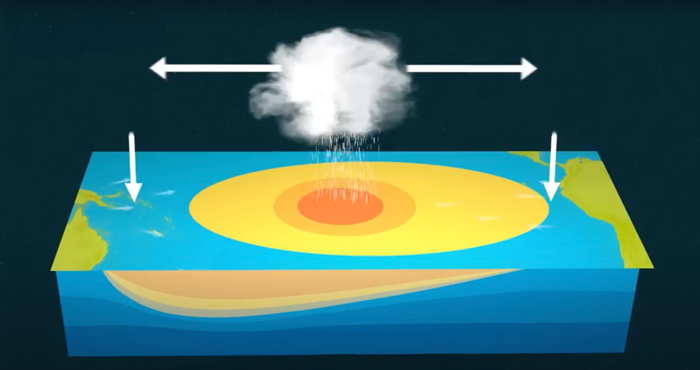

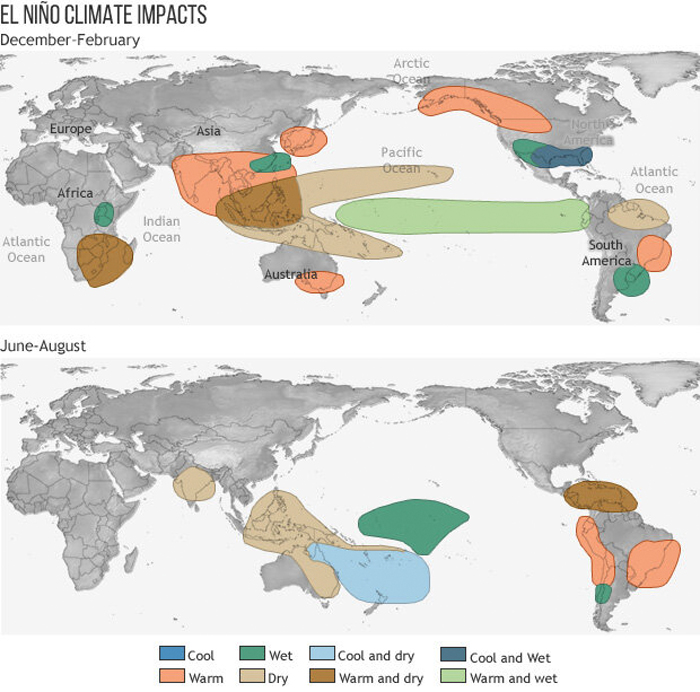

El Niño events are defined by their wide-ranging teleconnections which are large-scale, long-lasting climate anomalies / patterns that are related to each other and can affect much of the globe. During an El Niño event, westward-blowing trade winds weaken along the Equator. These changes in air pressure and wind speed cause warm surface water to move eastward along the Equator, from the western Pacific to the coast of northern South America.

Each El Niño event is different, so the global impacts can change. Usually it peaks around Christmas time and lasts for several months.

El Niño events of 1982-83 and 1997-98 were the most intense of the 20th century. During the 1982-83 event, sea-surface temperatures in the eastern tropical Pacific were 7.8-12.8° C (9-18° F) above normal.

Scientists collect data about El Niño using many different technologies. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), for example, operates a network of scientific buoys. These buoys can measure ocean and air temperatures, currents, winds, and humidity. The buoys are located at about 70 locations in the southern Pacific Ocean, from the Galapagos Islands to Australia.

These buoys transmit data daily to researchers and forecasters around the world. Using data from the buoys, along with visual imagery they receive from satellite imagery, scientists are able to more accurately predict El Niño and visualize its development and impact around the globe.

Image credits: NOAA

Following the work of Sir Gilbert Walker in the 1930s, climatologists determined that El Niño occurs simultaneously with the Southern Oscillation.

The Southern Oscillation is a change in air pressure over the tropical Pacific Ocean. When coastal waters become warmer in the eastern tropical Pacific (El Niño), the atmospheric pressure above the ocean decreases. Climatologists define these linked phenomena as El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO). Today, most scientists use the terms El Niño and ENSO interchangeably.

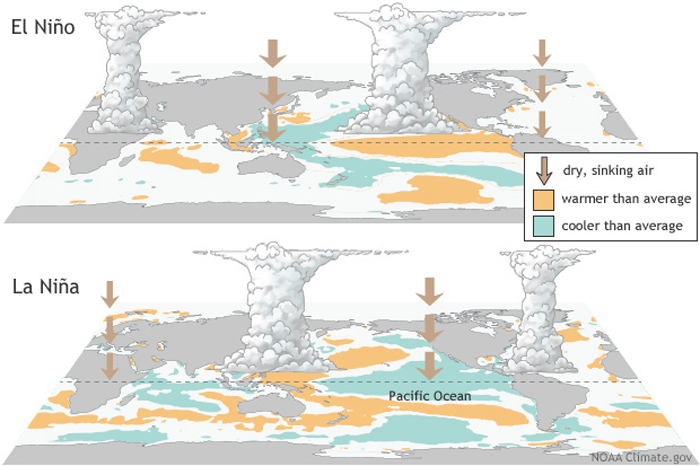

ENSO includes warm (El Niño), cold (La Niña), and neutral phases:

- Neutral: Easterly trade winds cause deep, relatively cool, nutrient-rich waters to rise to the surface along the coast of Peru and along the equator. Tropical Pacific sea surface temperatures are within +/- 0.9°F of normal;

- El Niño: Easterly trade winds weaken. Upwelling ocean currents along the coast of Peru and along the equator weaken. Surface waters in the tropical Pacific are warmer than normal;

- La Niña: Easterly trade winds strengthen. Strong upwelling of cold ocean currents along the equator and coast of Peru keeps warm surface waters in the western Pacific. Surface waters in the tropical Pacific are cooler than normal.

Image credits: NOAA

Also importantly, 2023-24 El Niño has peaked as one of the five strongest on record, bringing not only a huge ocean swell around the globe but a huge wave of heat as well. According to new research, there’s a 90 percent chance that global average surface temperatures will reach a record high, meaning this year could well surpass 2023 as the hottest ever.

However, from a surfing perspective, El Niño is usually a very good thing because it means more oceanic activity, more storms, and more waves.

Surfline’s forecast team’s recent discovery is exactly about that. They shared a video about how El Niño-driven storms made the entire world one big surfing spot.

Wave traveling 12,000 miles across the globe connected the entire surfer community

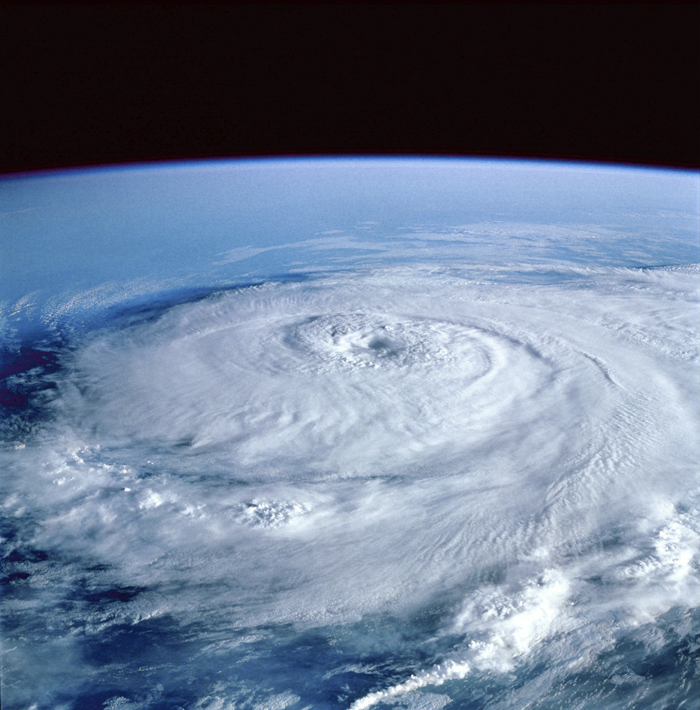

Image credits: Surfline

Image credits: Surfline

Image credits: Surfline

“Pumping Hawaii, fun surf the South Bay, the Gulf. Then you head on over to Europe and there’s just tons of waves there as well. For a storm to stay intact, travel out far and present that surf to all those different areas, it’s really special to watch,” shared the Surfline team.

“This everlasting storm went on to make a roughly two-week journey across the Pacific over North America and through the Atlantic Ocean, and it sent swells to nearly every stretch of coast on this side of the equator,” they added.

Surfers all around the world took a ride on the same swell made by El Niño

The storm was first noticed as it was pushing off Japan towards Hawaii by kicking off with some nice 8-10 foot waves. Then it weakened a bit and then really set up and deepened as it was off the US west coast.

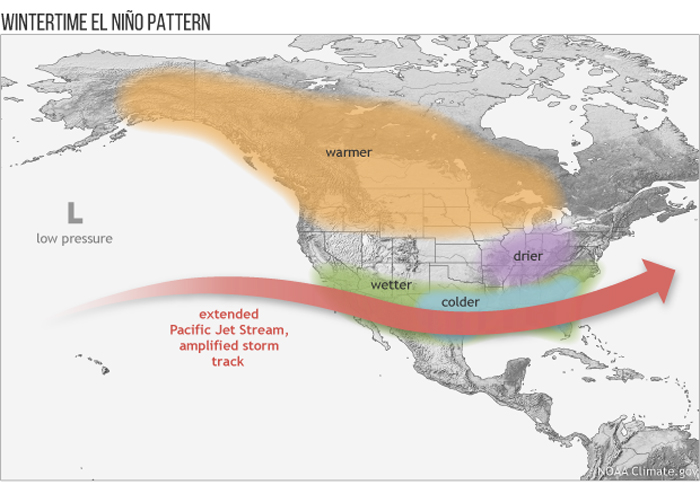

El Niño brought the storm track further and opened up to the potential to see stronger and more westerly swells for Southern California.

The storm system then continued to tap moisture from the Pacific as it made its way into the Gulf of Mexico. And as it re-emerged, it was still quintessentially the same storm system.

It moved through Texas and into the Northern Gulf, on its way through sending some surf to the region of North Florida. Then the load shifted to the Atlantic.

Also, some swell was sent to the Outer Banks and Northeast US. The storm wasn’t finished and reached hurricane four, strengthened the Caribbean swell window and got deeper into the Caribbean region.

Later on, the storm just kept tracking across the Atlantic, and the fact that it traveled across two oceans and made it pretty much intact is truly incredible.

Image credits: Pixabay (not the actual photo)

Image credits: drivemetotheocean (not the actual photo)

Yet stormy conditions are definitely more suitable for a skilled surfer. Speaking about waves, what’s no less important is the right selection of them. Caparica Surf Academy mentions that it directly influences the quality of each ride, the safety of the surfer and the potential for skill development. Choosing the right wave can mean the difference between a thrilling ride and a missed opportunity or, worse – an accident. Effective wave selection ensures that surfers maximize their time in the water, catching waves that offer the best potential for practice, improvement, and enjoyment.

For those hunting the most thrilling ride, I want to share a few places that have the biggest waves around the globe (based on SurfHub):

- Nazaré, Portugal: known for the biggest waves on Earth, up to 86ft

- Peahi, Maui: known for some of the biggest waves in the world, but also the most perfect too

- Cortes Bank, California: huge open-ocean waves with three separate peaks to choose from

- Mavericks, California: with powerful, heavy, slabbing big waves

- Puerto Escondido, Mexico: probably the most consistent big wave surf spot

- Wiamea, Hawaii: known for the legendary Eddie Aikau Big Wave Surfing Event

- Teahupoo, Tahiti: waves are breaking onto a shallow reef, producing arguably the world’s heaviest tubes

- Cloudbreak, Fiji: while other spots will be short, sharp, violent rides, Cloudbreak will keep on giving with rides upwards of 400m long

- Mullaghmore, Ireland: known for some of the heaviest waves on Earth

- Belharra, France: known for huge, mountainous lumps of swell that break in deep water

Image credits: Olympics

And here are some of the most beautiful places to catch the waves:

- Tavarua, Fiji

- Crescent Head, Tasmania, Australia

- Playa Grande, Rio San Juan, Dominican Republic

- Fernando de Noronha, Pernambuco, Brazil

- Waikiki Beach, Hawaii, USA

- Malibu, California, USA

- White Beach, Okinawa, Japan

- Bloubergstrand, South Africa

- Santa Bárbara, Azores, Portugal

- Praia do Norte, Nazaré, Portugal

Image credits: tavaruaislandresort

Image credits: tavaruaislandresort

Image credits: Bradley Hook

While scientists are trying to tame El Niño and are worried about serious global warming, when it comes to surfing, it’s slightly a different story: the bigger the wave, the more fun it gets to ride it. And of course, stormy weather is the best fuel for it!

12,000-Mile Storm Connected Surfers From All Around The Globe, Attracting Them To Ride It Bored Panda