A hidden "entrance to the underworld" built by the ancient Zapotec culture has been discovered beneath a Catholic church in southern Mexico, according to a team of researchers using cutting-edge ground-scanning technology.

The complex system of underground chambers and tunnels was built more than a millennium ago by the Zapotec, whose state arose near modern-day Oaxaca in the late sixth century B.C. and grew in grandeur as people created monumental buildings and erected massive tombs filled with lavish grave goods.

The architectural complex at Mitla, 27 miles (44 kilometers) southeast of Oaxaca, boasts unique and intricate mosaics, having functioned as the main Zapotec religious center until the late 15th century, when the Aztec conquest likely resulted in the abandonment of the site. The Spanish then reused stone blocks from the ruins to build the San Pablo Apostol church a century later.

Oral histories have long suggested that the main altar of the church was purposefully built over a sealed entrance to a vast underground labyrinth of pillars and passages that originally belonged to a Zapotec temple known as Lyobaa, which means "the place of rest."

Investigating this claim with modern geophysical methods, the Project Lyobaa research team announced on May 12 that they had found a complex system of caves and passageways beneath the church. The project is a collaboration of 15 archaeologists, geophysical scientists, engineers and conservation experts with the Mexican National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH), the National Autonomous University of Mexico, and the ARX Project.

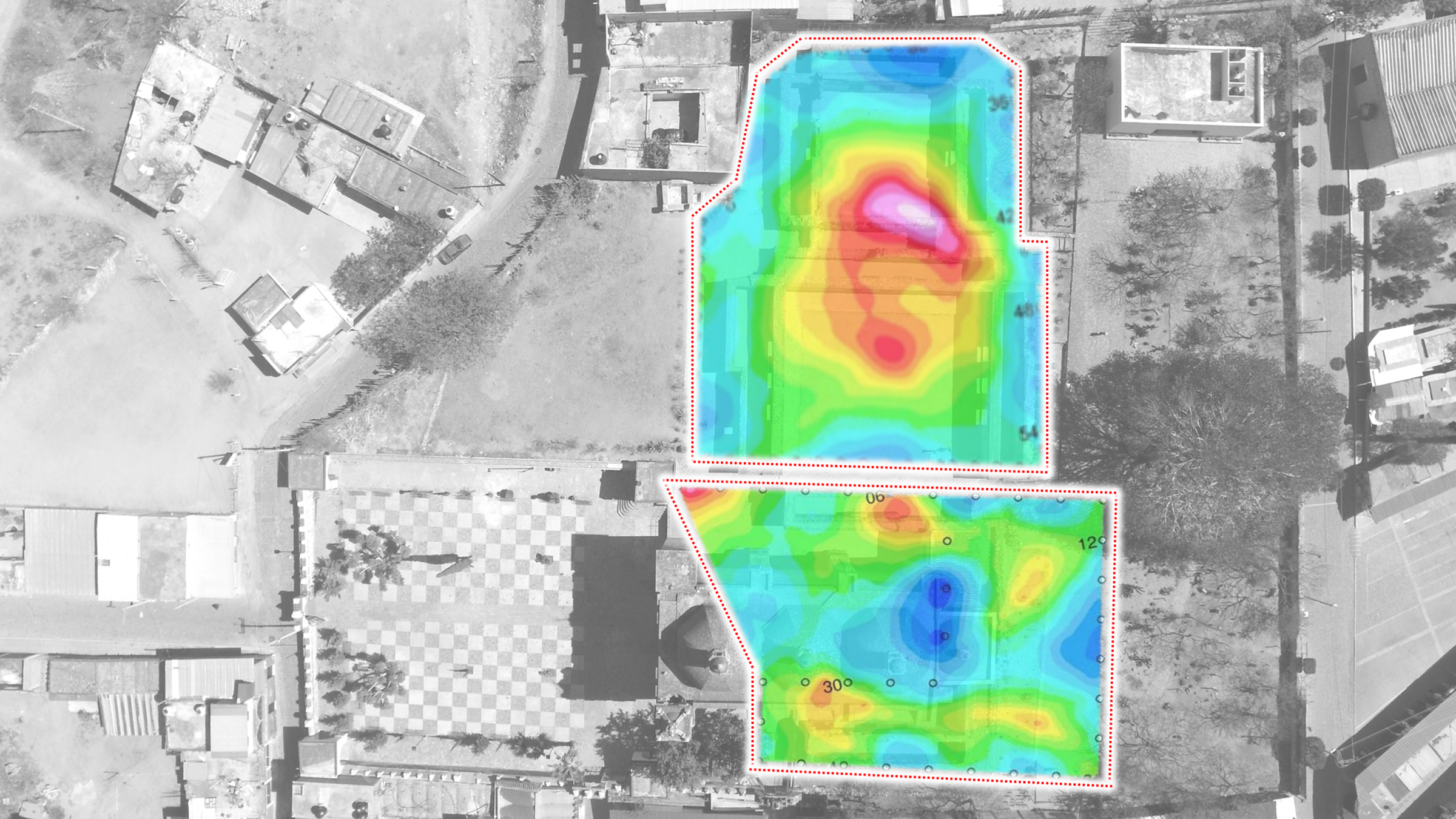

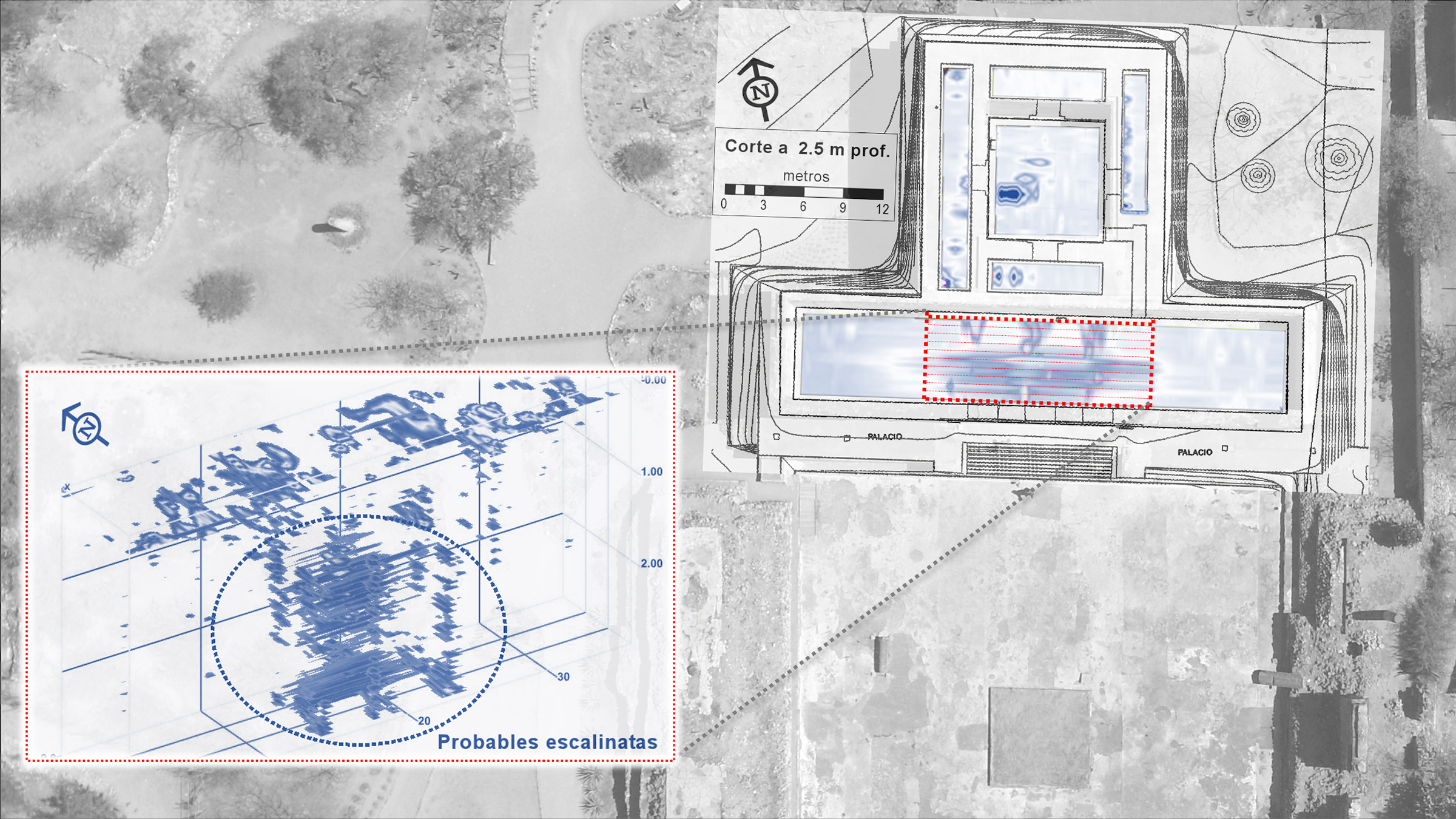

Using three nondestructive methods — ground penetrating radar, electrical resistivity tomography and seismic noise tomography — the team produced a virtual 3D model of the subterranean ruins. These methods work by measuring reflection properties of electromagnetic and seismic waves as they pass through different subsoil layers and other material underground. A number of measuring devices placed around the church recorded information about a large void below the main altar and two connecting passages, all at a depth of 16 to 26 feet (5 to 8 meters).

"The newly discovered chambers and tunnels directly relate to the ancient Zapotec beliefs and concepts of the Underworld," Marco Vigato, founder of the ARX Project, told Live Science in an email, "and confirm the veracity of the colonial accounts that speak of the elaborate rituals and ceremonies conducted at Mitla in subterranean chambers associated with the cult of the dead and the ancestors."

Although the team suspected that the underground temple existed, they were surprised by its scale and depth, according to Vigato. "More research is needed to accurately determine the full extent of these subterranean features," he said.

José Luis Punzo Díaz, an archaeologist at Centro INAH Michoacán who was not involved in the research, told Live Science in an email that "geophysical methods are very important in current archaeology." These methods have helped find anomalies at other Mesoamerican sites, such as Teotihuacán, which have also been interpreted as entrances to the underworld. As a result, these methods "should be contrasted with archaeological excavations," Punzo noted, "because although the geophysical data are interesting, it is always essential to verify them in the field."

The joint research team has plans for a second season of geophysical investigation in September, which will focus on additional groups of structures at Mitla, and they hope to get permission from authorities to conduct further work at San Pablo Apostol as well, Vigato said.

All told, "these findings will help rewrite the history of the origins of Mitla and its development as an ancient site," the team members wrote in a statement.