When we talk about the microbiome — the Marvel Cinematic Universe of microorganisms living within and on our bodies — the gut tends to take center stage. It isn’t without merit — research shows that the trillions of microbial belly dwellers are central to mental health, fighting cancer, sleep, and much more.

But we’ve got microbes hunkering down on just about any bodily surface they can reach. While we’ve still yet to uncover exactly how these diverse microbial niches impact human health and well-being, scientists are unraveling some insights on the microbiome smack dab in the middle of our faces. In fact, this nose, or nasal, microbiome may play an important role in shaping our immune response to respiratory infections like the flu and Covid-19. And just as an unstable gut microbiome is linked to illness, pesky bacteria in our schnozzes may be tied to asthma and maybe even neurodegenerative diseases. If we can nail down exactly how these diverse microbial niches impact our health, perhaps we can figure out how to keep our nose microbes healthy and in turn, prevent some of the common respiratory infections that start where these microscopic beings call home.

What exactly is the nose microbiome?

The microbiome collective on our bodies evolved alongside us as we went from prehistoric apes to modern-day humans and, for the most part, is acquired at birth. Newborns are slathered with bacteria as they pass through the vaginal canal and pick up more when breastfeeding from their moms. This early microbiome trains our immune system as we grow into adulthood (among many other important functions) and continues to change with age, diet, medications, lifestyle choices, local environment, and genetics.

Compared to the ginormous microbial zoo of the gut, the nose is a bit on the smaller side, Jessica Mark Welch, a microbial ecologist at the Forsyth Institute and the University of Chicago’s Microbiome Medicine Program, tells Inverse.

“The nasal microbiome is relatively simple, so if there is [something like] 150 bacterium in your gut, there’s probably like 10 in your nose,” says Mark Welch.

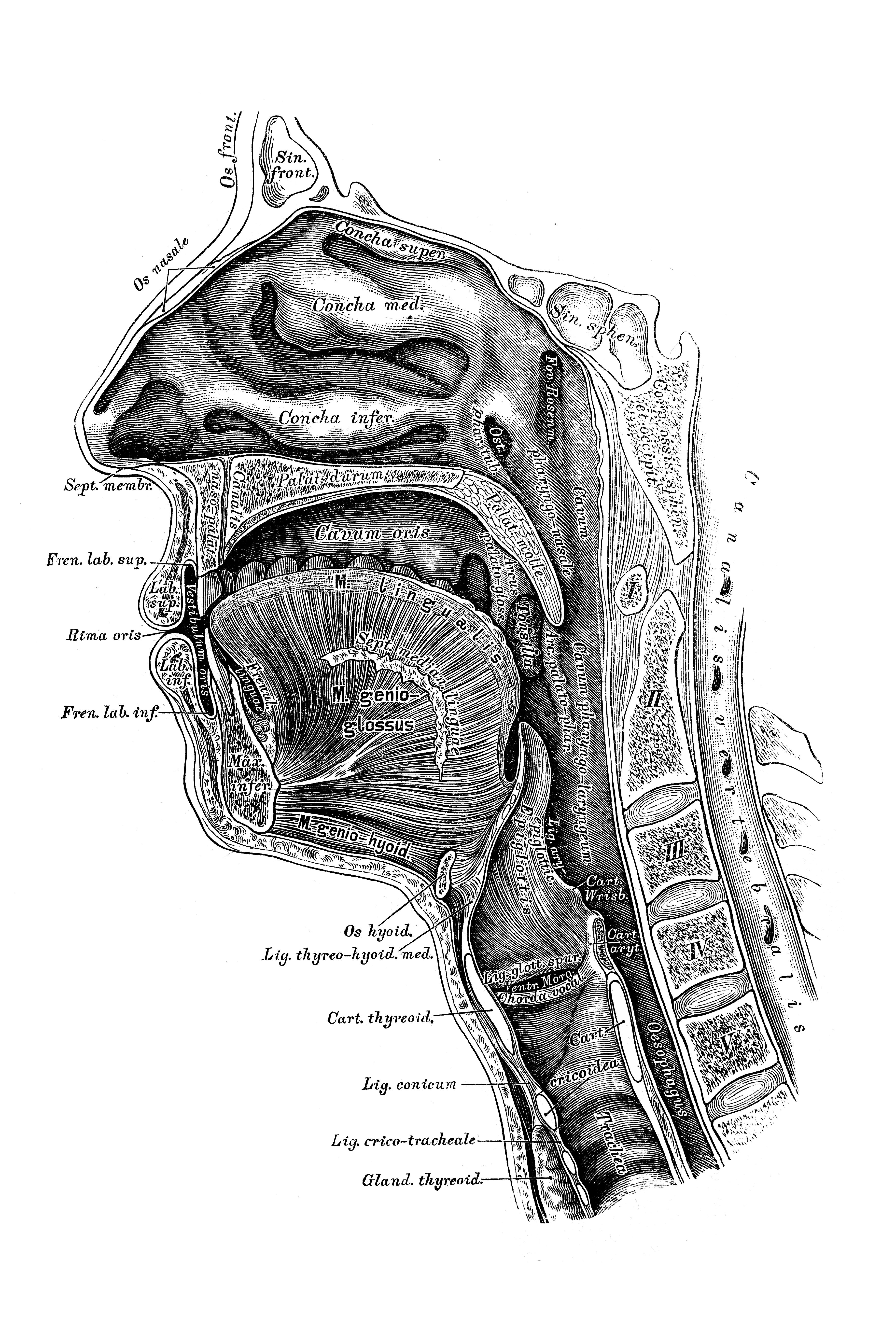

But don’t let the quantity fool you — the microbes of the nose, and the connected system of air-filled cavities within the skull called the sinuses, are still pretty potent in their own right. Studies have found these bacteria tend to be aerobes like Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, and Corynebacterium, meaning they require oxygen in order to live and grow, Zara Patel, a professor of otolaryngology at Stanford University School of Medicine, tells Inverse.

“In a healthy human being, there’s a predominance of what we call aerobic-type bacteria,” says Patel. “When you develop a predominance of anaerobic bacteria [which don’t require oxygen], that’s one of the signs of disease state, what we call chronic sinusitis.”

How is it involved in health?

Okay, so there’s an enclave of microorganisms hanging out in your nose (not freaky at all), but how are they important? Scientists are still parsing that out — as they are doing for the entire microbiome in general — but the most apparent function is protecting us against foreign invaders zipping up our nostrils. For example, a 2021 study published in the journal Cell Reports found that in patients infected with Covid-19, the nasal microbiome shifted toward a pathogenic bacteria called Pseudomonas aeruginosa whose growth was likely encouraged by the coronavirus. The study also found that this disruption in the nasal microbiome also appeared to be associated with elevated inflammation and diminished tissue repair. Other studies also suggest the nasal microbiome might be crucial against the flu, particularly to enhance the body’s immune response after vaccination.

Aside from respiratory infections, the nasal microbiome may be at the center of inflammatory conditions like sinusitis, asthma, and allergies, Hariom Yadav, director of the University of South Florida’s Center for Microbiome Research, tells Inverse.

“In allergic reactions, hypersensitivity happens because the immune cells lose tolerance,” says Yadav. “If there are good bacteria [in the nose], they will increase the tolerance [and thus] less hypersensitivity happens. But at the same time, if there are bad bugs there, they may exacerbate hypersensitivity.”

One good bug, in particular, may be Lactobacillus, a bacteria known for making lactic acid which it uses to kill other microbes. A 2020 study published in the journal Cell Reports found that the nasal microbiomes of healthy people tended to have up to 10 times more of this bacteria compared to people with chronic nasal and sinus inflammation. The finding was a bit surprising since Lactobacillus don’t normally thrive in oxygen-poor areas but, in the human nose, appeared to have adapted to its oxygen-rich environment.

Additionally, there’s research linking nasal microbe shifts that favor inflammation with age-related macular degeneration, where the back part of the retina, called the macula, becomes damaged with age, resulting in vision loss. The nasal microbiome may even be involved in neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s, where it’s believed disruption in the delicate microbial balance leads to inflammation and damages neurons in the nose that convey information to the olfactory bulb, a structure at the bottom of the brain overseeing our sense of smell (loss of smell is considered an early sign of the disease).

Is there anything we can do to protect it?

There isn’t any magic bullet to a better nose microbiome, but there are definitely things you can do to safeguard it. For one, not overdoing antibiotics, says Patel and Yadav, which, while killing bad, pathogenic bacteria, also indiscriminately kill good ones too.

“We know that the more antibiotics we take, the more our microbiome shifts further and further away from normal with each course of systemic antibiotics and is likely selecting for the type of bacteria that can become pathogenic,” says Patel.

Follow that up with good lifestyle choices like not smoking, which encourages harmful bacteria that colonize the nose and other neighboring microbiomes of the mouth and lungs. A well-rounded diet rich in fiber could help indirectly foster a healthy nose microbiome as it directly does a gut microbiome. There’s evidence suggesting fermented foods like kimchi or sauerkraut may boost the diversity of the gut microbiome and improve immune responses. It’s not difficult to imagine the nose microbiome could benefit from deliciously fermented goodness in some way as some studies suggest a link of sorts connecting gut health to lung health — a gut-lung axis, if you will — as seen with asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, and potentially Covid-19.

If you’re thinking of supplementing your diet with probiotics, there are products commercially available, but Patel says that, unfortunately, there’s not a whole lot of evidence behind them, and she doesn’t recommend them.

“We really need more information about exactly which bacteria are good and bad, and it’s not even as simple as that,” says Patel. “My microbiome in my nose and sinuses is not exactly the same as your microbiome even if we’re both completely healthy [individuals]. And it’s not just the type of bacteria [but] the ratio of bacteria to each other.”

There’s a lot of potential for the nose microbiome, and research is still very much in its infancy, says Mark Welch, Patel, and Yadav. The sort of clinical approaches using the gut microbiome, like fecal microbiota therapy (aka poop transplants), may one day be the same for the nose to treat a wide array of respiratory disorders. Clinical trials are underway in Australia and Canada to see if transplanting healthy nasal microbiomes will help folks suffering from chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS), an inflammatory condition of the nose and sinus.

The bottom line, there’s more to a good microbiome than just your gut. Your nose definitely knows.